With Taylor Swift’s concert film The Eras Tour set to hit theaters across the globe next week, perhaps it’s a little too early to proceed with this list of 10 great performance films. After all, the pop superstar’s popularity has pundits predicting a $100m-plus take, one that would break the record for the highest-grossing concert film of all time, currently held by Justin Bieber’s Never Say Never ($73 US) and followed closely by Michael Jackson’s posthumous This Is It ($72m US). Maybe T-Swift’s film will be as great as (as my daughters tell me) her concerts and break its way into this list of fave rock performance films. Or maybe Beyoncé—already on this list—will follow suit with another concert film in her wake.

Either way, a cinema ticket will surely be cheaper than a concert, anyway. And that’s part of the appeal of the performance film, to re-create the concert experience for those who couldn’t—or couldn’t afford to—attend the real thing. It’s a genre that’s been in existence since 1964, when The T.A.M.I. Show brought to movie screens a Santa Monica concert headlining The Rolling Stones, the Supremes, The Beach Boys, and an incendiary James Brown and the Famous Flames. Its success led to that of the late-Sixties’ most famous performance films, and two highlights of this list—Monterey Pop and Woodstock—films that defined a generation.

Before The T.A.M.I. Show, it was only on television one could see rock and pop stars perform live, unless you counted the occasional newsreels or the short-lived Panoram “Soundies” of the war era. So since 1964, performance films have been doing fans a solid, bringing the stars to their local cinema, on a big screen with booming sound, re-creating if not exactly replicating the concert experience. Sometimes they’re little more than a money grab, but the best of these will surely please any fan.

10. The Last Waltz

Let’s dispense with the preliminaries and luminaries first. Martin Scorsese’s 1978 chronicle of what was intended to be The Band’s last performance (it wasn’t) aimed for the celebratory and felt more like the elegiac. You could hardly blame The Band themselves, nearly two weary decades into their life on the road with their quirky Americana, struggling with the weight of addictions, illnesses both physical and mental, and no shortage of fatigue and ennui, bearing down hard on all five of them: Robbie Robertson, Rick Danko, Garth Hudson, Levon Helm, and Richard Manuel.

Scorsese, at the time the shining young star of New Hollywood with Taxi Driver, collaborated with Robertson, primarily, on both the visual inspirations for the film and the guest list, which ranged from the obvious co-conspirators (Ronnie Hawkins and Bob Dylan, both of whom The Band had backed) to the era’s rock gods (Neil Young, Van Morrison, Eric Clapton), their mentors and inspirations (Muddy Waters, Paul Butterfield), to some less obvious cameos (Joni Mitchell, Neil Diamond, the poet Michael McClure). Also served up on a platter alongside the rich feast of guest performers: Thanksgiving dinner for all in attendance, just to complicate matters a bit more.

The Last Waltz can feel a bit like that weight you feel after turkey with cranberry sauce. But Morrison is in particularly fine fetter on “Caravan,” and Helm’s inspired vocalizing with the Staples Singers on “The Weight” is testimony itself to the group’s place in the world, well worth the price of admission all by itself. He and the Band-mates, sans Robertson, would keep on touring for years, so it wasn’t the “last” waltz after all, but it made for a beautiful, rich feast of a film.

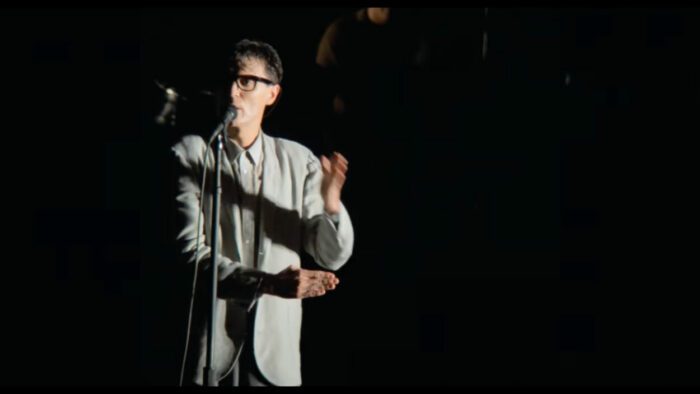

9. David Byrne’s American Utopia

One of two Covid-era pieces I’ll tout here, David Byrne’s American Utopia brought the singer’s Broadway performance to streaming when we needed it most: alone in our living rooms, isolated by the pandemic, reeling from the murder of George Floyd, in a country pulling itself apart at the seams. A minimalist set constrained to a single unadorned square space, just eleven performer-instrumentalist-singer-dancers, no dressing or props, and a muted, monochromatic palette would hardly seem the site of the kinds of passion and good will Byrne and corps can imbue, but the whole set is a gas, gas, gas.

Ever the canny performer, Byrne commands our attention with Talking Heads hits, solo selections, and covers, while Annie-B Parson’s choreography is marvelously inventive. For as diverse as the song selections might seem, they culminate in a passionate catharsis celebrating the collective ecstasy of music we were so desperately missing in 2020. Spike Lee, whose talents as a director of performance are too often overlooked—he got his start at Morehouse College filming step shows, after all—doesn’t miss a beat anywhere, stalking the performers while they work their magic across the stage.

8. Woodstock

One could probably make a damn good documentary from the concert footage that didn’t make its way into the 185-minute theatrical cut of Woodstock: there was Tim Hardin, Ravi Shankar, Melanie, Mountain, the Grateful Dead, Creedence Clearwater Revival, The Band, Johnny and Edgar Winter, Paul Butterfield, and Blood, Sweat & Tears (subjects, themselves, of a recent rock-doc) to pick from. Fortunately, the three-day 1969 festival had plenty more on the roster, from opening act Richie Havens to closing performer Jimi Hendrix, with a bevy of all-stars in between.

It was a diverse range of talents: Joan Baez, The Who, Canned Heat, John Sebastian, Arlo Guthrie, Santana, Janis Joplin, Jefferson Airplane, Crosby, Stills, and Nash, and more. The film took almost as many editors (seven in all, including future collaborators Thelma Schoonmaker and Martin Scorsese and the film’s director, Michael Wadleigh) to make sense of it all, but the film was a massive commercial and critical success, earning itself a reputation and a legacy as the film that defined a generation and one Roger Ebert called “maybe the best documentary ever made in America.”

7. Bo Burnham: Inside

What’s this doing here? Isn’t Bo Burnham: Inside just another more musical iteration of the comedian’s stand-up specials? Another show on a streaming service? Perhaps, but to my thinking it’s also far, far more. In the first year of the coronavirus epidemic, there were no live audiences; there were only performers holed up at home, their Zoom platforms and webcams their only means of connecting with fans. Some great art emerged from those who embraced the lockdown: Taylor Swift reinvented herself as a cottagecore troubadour, for instance, and artists from Paul McCartney to Charli XCX embraced the times with records made in varying degrees of isolation. Burnham took it upon himself to write, perform, and record an album’s worth of new material in a staged, self-imposed lockdown, making himself something of a millennial man-with-a-movie-camera.

The result is genius, and (yes, it earned a single-night theatrical release) one of the best performance films ever, deploying a small array of GoPros, webcams, and small DSLRs to their full cinematic expression with lo-fi lighting tricks, clever conceits (the sockpuppet’s a sockpuppet; get it?), and memorable songcraft all devoted to the fragility of the singer’s mental wellness in a time that would pose it (and ours) no small challenge. Bo Burnham: Inside is the outlier on this list, where most performances involve bands and arenas, festivals of communion. Let’s hope it’s not a type of performance that is warranted again. But for a moment in the pandemic era, it made for a briefly bright, beautiful performance of one.

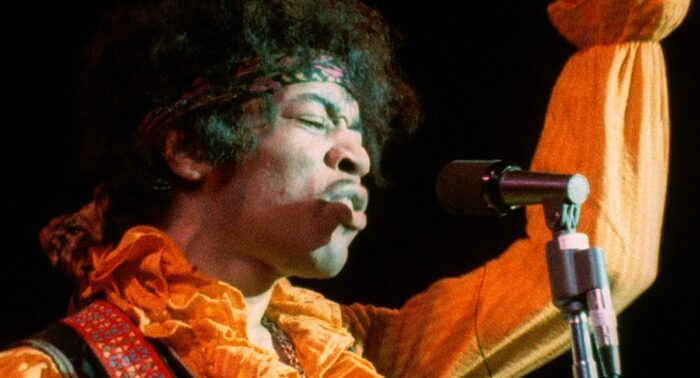

6. Monterey Pop

American Direct Cinema meets the Summer of Love, with Jimi Hendrix lighting his guitar on fire to mark the occasion. Director D. A. Pennebaker, who’d already made his mark on the rock-documentary form with his vérité approach to Dont Look Back, kept his lens trained on the wildly diverse festival’s signature moments. Hendrix, Janis Joplin, and Otis Redding were among them, as were folkies The Byrds, The Mamas and Papas, and Simon and Garfunkel; rockers The Who and Moby Grape; and other acts as diverse as Hug Maskela and Ravi Shankar. With his Direct-Cinema pals Albert Maysles and Richard Leacock shouldering cameras, Pennebaker and crew did not miss a single beat, and Monterey Pop captured the love and fury of a new generation.

What could be better? Criterion has released a Blu-ray set not only of Pennebaker’s film as released in 1968 but scads of bonus footage, including sets that never made it into the cut from the Association, the Blues Project, Buffalo Springfield, the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, Country Joe and the Fish, the Electric Flag, the Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane, Al Kooper, the Steve Miller Blues Band, Laura Nyro, Quicksilver Messenger Service, Tiny Tim, and more, not to mention the full sets from Redding and Hendrix.

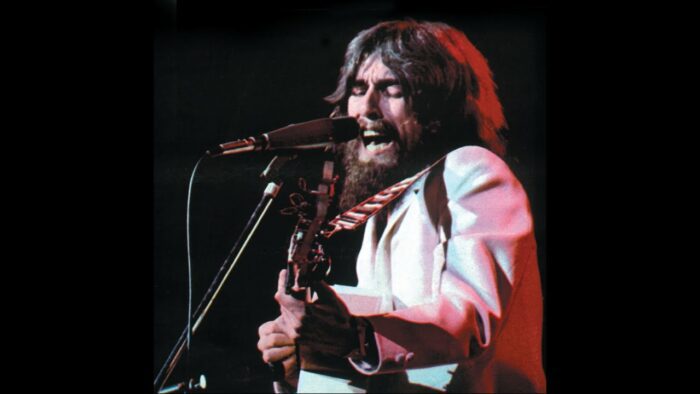

5. The Concert for Bangladesh

In the wake of the breakup of The Beatles, it was quiet George Harrison who made the most noise, first with his stunning three-disc magnum opus All Things Must Pass (and its lovely singles “My Sweet Lord” and “What Is Life”) and then with what was the first of many benefit concerts bringing all-star rosters to raise relief funds for the impoverished. In this case, it was Harrison and his good friends Eric Clapton, Ringo Starr, and the unbilled Bob Dylan heading the lineup with Leon Russell, Billy Preston and Ravi Shankar filling out the bill. (For the record, John Lennon and Paul McCartney declined.)

From a technical perspective, The Concert for Bangladesh—actually two concerts, one in the afternoon, the other that same evening, performed on August 1, 1971—is certainly the worst film on this list and far short of spectacular by any measure. One of the key cameras was out of focus throughout, rendering a good deal of footage nearly unusable. On the opposite side of the stage, cables obscured the view of the other main camera. Editing between the two performances, with different lighting schemes, sometimes even different clothes worn by the performers, is often messy. Audio sync between the two was a convoluted, inexact process, with the performances varying in tempo and volume. Harrison oversaw the editing himself, which might explain why it took until the next year for the final product to reach the theaters.

Who even knew if the concert would pull off? The Beatles were a thing of the past, as were the glories of Woodstock. Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, and Jim Morrison were all dead. Eric Clapton, by some accounts, was nearly as well, deep in the throes of heroin. Harrison himself was notoriously stage-shy. But he cajoled his friends, lined up UNICEF, put together a crack stage band, and on one night’s rehearsal (sans Clapton) managed to pull off a blissful work of stellar songcraft and philanthropic good cheer. The Quiet Beatle was never so impassioned onstage as when singing “My Sweet Lord” or trading licks with Clapton on “While My Guitar Gently Weeps.”

For all its raggedness, the film is a treasure. It’s a bit of a hoot to watch the audience applaud Shankar and his band tune up, not knowing they weren’t yet actually performing, or to watch Harrison forget the lyrics to “Something,” perhaps his best-known Beatles song. Performances are uneven but charming, and for a long time, the pairing of Starr and Harrison was as close to a Beatles reunion as fans got. (And good old Ringo is still belting out “It Don’t Come Easy” five decades later!) The dozens of similar projects undertaken by Bono, Bob Geldof, John Mellencamp and others over the years, as treacly as they could become, owe a debt to the OG Concert for Bangladesh.

(And if you are a fan, do watch The Concert for George (2002), which features a spectacular guitar solo by Prince that concludes “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” with a bit of heavenly sleight of hand.)

4. Homecoming

Homecoming was, to use an ungainly word, precedented. Beyoncé had already dropped her surprise eponymous visual album five years prior, and then of course there was her stunning film Lemonade, inspired in part by the landscapes, characterizations, design, and motifs of L.A. Rebellion auteur Julie Dash’s enigmatic Daughters of the Dust. Following these, was there any doubt that Queen Bey’s Netflix concert film would wow, not just as an aural spectacle, but a visual one as well?

None indeed. Headlining Coachella, the first time a black woman had ever done so, writer-director-executive producer-star Beyoncé commands the crowd’s attention like a modern-day Cleopatra with a cast of hundreds and a throng of rapt admirers. Busting moves, shaking booty, dropping rhymes, Bey rules the roost. Between the performances are quotations from Audre Lorde, Nina Simone, Toni Morrison, WEB DuBois and more, situating the singer in the context of those artists and writers she admires and follows. And reminding us all of just how infrequent it its, sadly, that spectacles like hers have made their way to mass audiences.

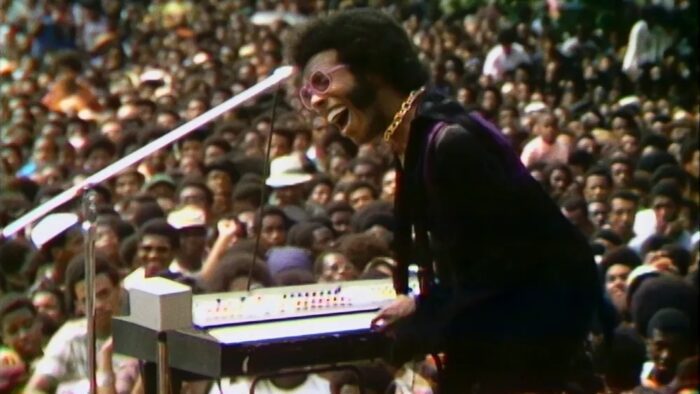

3. Summer of Soul

If so far, aside from Beyoncé and a handful of guests in Monterey Pop and Woodstock, you’ve noticed the overwhelming whiteness of this list, you’ve realized that somehow black performers have found themselves at the periphery of the very idiom they invented. Aside from Queen Bey’s stunning breakthrough, had any black rock act headlined a performance film? (Seriously. You tell me.) This overt inequity makes Summer of Soul both a welcome sight and a sober realization. Somehow, one of the great concert series in rock history—the Harlem Cultural Festival of 1969, featuring Sly and the Family Stone, Nina Simone, The Staples Singers, B.B. King, Stevie Wonder and more—was recorded, but scarcely seen, until 2021.

I’m riddled with both bliss and anger at saying so. But let’s focus on the positive. The Roots’ Questlove interweaves the performances with brief on-the-street interviews, setting a context of loss and pride in the wake of the deaths of Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, Jr. and Medgar Evers. Is it any wonder the black people on the street are less than enthralled with the Apollo flights than the crime and poverty directly in front of them? For a first-time documentary director, Questlove sets the stage for the enthralling, uplifting music perfectly. Try not tapping your feet to the Edwin Hawkins Singers’ “Oh Happy Day.” Summer of Soul needed to be seen far earlier than 2021, but we have every reason to thank Questlove and his crew for bringing it to life, a long-lost cousin to its time-companion Woodstock, even if some 70 years after the fact.

2. Sign ☮ the Times

There may be no one single trait that makes for a great performance film. It might be a sui generis approach to the concept (Bo Burnham: Inside), a generational moment (Woodstock), or a long-overdue reclamation (Summer of Soul). Or, like Homecoming, it might just be as simple as a great performer at the zenith of their artistic output. Such is the case with Prince’s Sign ☮ the Times, the concert document of his 1987 double-album follow-up to Purple Rain. That record marked a turning point in Prince’s career as he slashed ties with the Revolution and co-collaborators Wendy Melvoin and Lisa Coleman, forging ahead as a solo artist on a new and uncharted path. It was a little less commercial than Warner Bros and many fans expected, but it didn’t lack one but in creativity or idiosyncrasy, yielding some of The Artist’s best work. His best album? Yeah, I’ll die on that hill.

At the time, though, sales were, for Prince at least, middling, and his response was “I’ll show them”—with a concert film he directed himself. Footage from Netherlands concerts was deemed unusable, so he re-recorded performances at his own Paisley Park. You can’t fault the crack band or the taut 13-song setlist—as a musician, Prince was at his peak—but for some reason, audiences didn’t respond, and the film did nothing to boost the flagging sales of the album. And Sign ☮ the Times disappeared from theaters and was soon clogging up VHS bins at Wal-Marts. Sadly, it’s all too rarely seen, having been out of print on home media in the U.S. since 1991. Last year, the Criterion Channel streamed it for a short while, raising the specter of a home-release possibility, and you can find it today on budget streamers like FreeVee, but if anything deserves the special-edition treatment, it has to be Sign ☮ the Times, one of the great performances by one of the greatest performers of all time.

1. Stop Making Sense

Speaking of special treatment, perhaps the very best performance film of all time is back in theaters as of this writing. A24, a studio that can practically do no wrong, has brought Stop Making Sense back to theaters in a newly restored in 4K edition for the 40th anniversary of its release. A close collaboration between director Jonathan Demme and Talking Heads, Stop Making Sense stars core band members David Byrne, Tina Weymouth, Chris Frantz, and Jerry Harrison along with Bernie Worrell, Alex Weir, Steve Scales, Lynn Mabry and Edna Holt; Harrison remixed the audio for its theatrical release. The band’s live performances, shot over the course of three nights at Hollywood’s Pantages Theater in December of 1983, feature some of their most memorable songs, from “Psycho Killer” to “Burning Down the House” (from Speaking in Tongues, their most recent album at the time), with the Tom Tom Club’s brilliant “Genius of Love” and the band’s rollicking cover of Al Green’s “Take Me to the River” closing things down.

Big suits, boomboxes, and all, Stop Making Sense is as good as performance films get; check out my Film Obsessive colleague Jay Rohr’s review of the recent theatrical release. Now, all the world needs is a special edition 4K home media disc, and we’ll finally be happy!

Honorable Mention: Every fan will tout his or her own favorite performer’s film. Nothing wrong with Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, Pink Floyd: Live at Pompeii, The Who Live at the Isle of Wight, Nirvana Live at the Paramount, Neil Young: Heart of Gold, Buena Vista Social Club, Standing in the Shadows of Motown, or to go back even further, Elvis: The Comeback.

Also check out: my Film Obsessive lists of the best rock fiction films, documentaries, and biopics for more. Altogether, these 40-plus films ought to have you rockin’ out ’til the house burns down!