Some scenes are so iconic that they take on a life outside the film. For example how many people know the ending of Planet of the Apes or the shower scene in Psycho? How many of these people have likely seen the original film?

The transformation scene in 1927 film Metropolis has a similar ubiquity: a feminised machine surrounded in circles of light transforms into a human woman. It’s an instantly recognisable clip and image used by journalists as a shorthand for science fiction.

It was not the first on-screen robot but it is the one that caught the public imagination. Partly because the robot is feminised, which was a cinematic first, but also the idea of a robot masquerading as a human plays on our fears of technology making us redundant. Like the creature in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, Robot Maria challenges perceptions of beauty and virtue. Unlike the creature, Robot Maria is psychopathic, yet we root for her anyway, because she brings down an unjust society.

Disguised as the virtuous, spiritual leader of the workers, Robot Maria assimilates herself into human society and causes havoc. Her rampage influenced generations of Sci-Fi writers and film-makers to create stories of robots going rogue.

Metropolis is a modern parable that blends religion, horror, fairy tales and science fiction together, half a century before Luke Skywalker picked up a lightsaber. The man-machine design also strongly influenced C-3PO.

The white haired, eccentric Rotwang was the original mad scientist and a direct influence on Universal’s depiction of Frankenstein’s creator four years later: his lab is full of Tesla coils and bubbling chemicals.

Outside film, the visual iconography, themes and motifs have influenced generations of artists as diverse as Kraftwerk, Motörhead, Queen, Janelle Monáe, Lady Gaga, Sepultura and St Vincent.

Not bad for a film made during Weimar Republic era Germany that nearly bankrupt its studio, was critically panned, and was then cut from three hours down to 90 confused minutes. The film was intended to challenge Hollywood’s international domination but it flopped.

Years later, the half-Jewish Fritz Lang was called to Goebbels office to be told that both him and Hitler were fans of the film, and they asked if he wanted to make a film for them. A few months later, Lang fled to America. While his ex-wife, and Metropolis screen writer, Thea Von Harbou stayed and would go on to direct, write and produce films for the Nazi Party.

After WWII film critics treated Metropolis like a crime scene and dismissed it as pro-fascist. Lang, who was now considered one of the great Film Noir directors, also disowned the film saying it was too naïve.

Yet the film found new life with New Romantics when it was “remixed” by Giorgio Moroder in 1984 who tinted the negative, added subtitles and gave it a ’80s soundtrack of Bonnie Tyler and Freddie Mercury. The film was reborn as high end camp. But the original’s critical reputation also started to improve when feminist critics started to champion the film.

Then in 2008 the film was restored to 95% of its original length after lost footage was found in Bueno Aires. Scenes, such as the fight between Joh and Rotwang, were still missing but the film now made sense.

Lesser films wouldn’t have survived, but beyond its cultural legacy, Metropolis (in its current form) plays like a modern blockbuster: it tells a straightforward story with complex ideas bubbling under the surface.

In the Depths

Although highly influential, Metropolis is less interested in the science and more the fiction. Contemporary critics, like H G Wells, were quick to dismiss the film as all style and no substance: pointing out that the city machine of Metropolis has workers doing menial tasks that industrial automation had already made redundant. The man-machine and inner city planes aside, this was Industrial revolution chic dressed up as the future (2026 to be precise).

Such concerns are unlikely to trouble a modern audience raised on pulp sci-fi, superheroes, Star Wars and Steam Punk. Even if they spot the anachronisms, they are unlikely to care. From the opening shots of the City of the Workers deep underground, to the Son’s Club stadium, this film is not shy about showing off its budget. It’s a film to lie back and take in the scenery, and not to get bogged down in the finer details.

Metropolis was intended to be a blockbuster that would appeal to the mass international market, and Van Harbou’s script doesn’t skimp in its nods to religious texts and popular novels. There’s Biblical references to Babel, the Garden of Eden and the Whore of Babylon. Freder’s vision of the Moloch comes from Jewish tradition. The class swap of Freder and worker 11811 riffs on the Prince and the Pauper and the final battle on the top of the cathedral invokes the Hunchback of Notre Dame. Moroder continued in this spirit when he updated the title cards for his 1984 version by describing the workers’ living situation as “Dickensian” and the scientist Rotwang as a “sorcerer”. For all its futuristic tech, this was a film rooted in tradition.

Its finest moments are when the mysticism and science clash, such as the vision sequences.

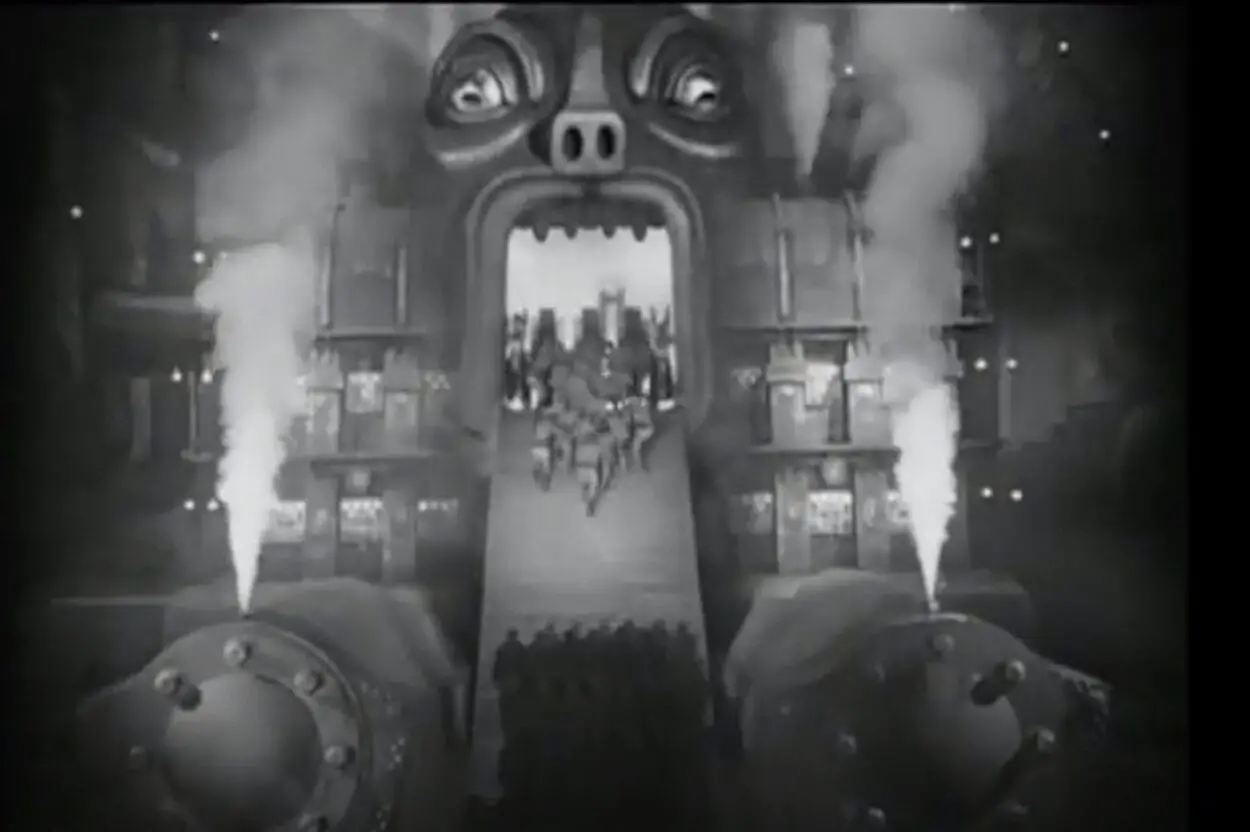

In the first, it’s visual trickery that blends the two worlds. A malfunctioning machine explodes, throwing our hero Freder to the ground, he lifts himself up and the machine turns into the gaping mouth of Moloch; a deity to which children were sacrificed. The camera focuses in on the guards at the top of the stairs throwing shackled slaves into the gears of the machine but then—in a still awe inspiring moment—droves of workers in overalls suddenly emerge from the floor and willingly march themselves into Moloch. Through clever editing and perspective, we see Freder’s world view being overturned.

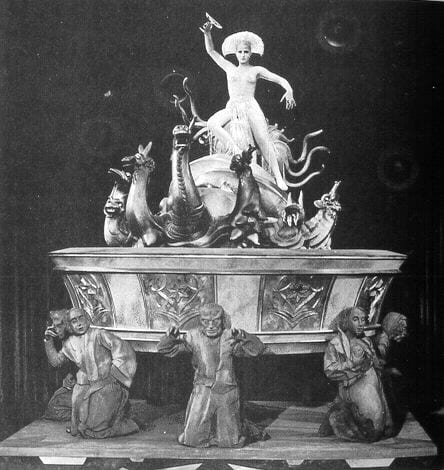

The second vision uses a montage to recreate a fever dream. After a mental breakdown, Freder bolts up from his sick bed looking straight at the viewer. The film then cuts between the upper classes leering at Robot Maria’s erotic belly dancing, Death playing a bone flute (not a euphemism) to summon the statues of the seven deadly sins to life, and a priest’s prophesies about Armageddon. The climax of the dream is Robot Maria being raised in the air on the top of a model of a seven-headed beast. She becomes The Whore of Babylon herself as depicted by the priest earlier in the story. Freder collapses back onto the bed and the scene fades to black. The audience takes a gasp and waits in anticipation of what’s next.

Like Frankenstein, for all it’s science, at heart Metropolis is a gothic horror. It’s only in the places that resist the attractive lure of Metropolis—Rotwang’s medieval house, the catacombs and cathedral—that the truth can be spoken out loud. While at top of the Tower of Babel, Joh Frederson is so feared that even his son is reluctant to let the door slam in case it interrupts him.

German Expressionist cinema had already given us horror icons such as Nosferatu and Dr. Caligari, and Metropolis attempts to create one more in the same style with Fredersen’s goon Thin Man. Played with wide-eyed relish by Fritz Lasp, he dresses like an undertaker and tries to be inconspicuous despite physically towering over everyone. Compared with the rest of the cast’s more naturalistic acting—even Rotwang has moments of sensitivity—he is so out of place it’s unintentionally comic at times. His performance is often reminiscent of Lurch in The Addams Family: shuffling around Metropolis looking at everybody with dismay. That being said he provides a moment of genuine terror when after discovering 11811’s hat, as he very slowly turns his head to Josephat (and to the audience) and flashes him a menacing smile. The menace is palpable.

The film’s darkest sequence—both literally and metaphorically—comes when Maria is being chased through the catacombs by Rotwang. He cruelly teases her and puts her on edge, by knocking over stones and shining his torch on the loose skulls. He then slowly lets the torch light travel up her body, like a physical manifestation of the male gaze, causing her to squirm. When Maria tries to run again, the whole shot is in darkness apart from Rotwang’s torch light that follows her every move. The audience is seeing things from Rotwang’s point of view, making them an accomplice as he blinds her and sends her in hysterics. John Carpenter used the same trick at the start of Halloween to get us into the eyes of Michael Myers.

For all its nods to the past, Metropolis feels chillingly relevant. The type of city machine depicted will unlikely ever come to pass, however the theme of men and women living for the machines seems apt for a generation compelled to look at their phones every five minutes.

The Head and the Hands

Metropolis society can be divided into three different sections: the working class who live deep underground in the City of the Workers, the upper classes who live above ground, and the Visionaries, represented by Joh Fredersen, the architect of Metropolis, and Rotwang the scientist.

The Visionaries are god-like and are aloof from society. Joh isolates himself at top of his Tower of Babel, which is crowned with thorns and is surrounded by staff who fear him, while Rotwang lives alone in an old Medieval building marked with pentagrams, bitter about how Joh stole the love of his life.

This physical and emotional distance of the Visionaries from the City of the Workers is summed up by the film’s opening epigram:

The mediator between head and hands must be the heart!

There is no middle class in Metropolis and the consequences of this are apparent when Josephat tries to commit suicide after being sacked by Joh. Freder pleads with his father to rehire him as to be sacked is to go the “depths” but his father refuses. It’s this lack of safety net that gives Joh his power.

This lack of mediator and communication between the classes is what Rotwang and Robot Maria later exploit. Maria conveys the danger of this to the workers through the story of Babel, using it as a prophecy, however her take on the Bible story alters some important bits. It’s not God that brings down the tower but the “hands” that built it as they know “nothing of the dream of which the head that had conceived it.” In the flashback the architects earnestly look at a small model of Babel like passive gods while thousands of slaves (“outside hands”) struggle to move the large stones required.

In Metropolis, the “outside hands” are the workers keeping the city going. They don’t enjoy the 24 hours of leisure activity of those above ground, they work to the 10 hour clock of the machine. The opening scene of the film cuts between their despondent shuffling to and from work, and the moving pistons of the machine. They are physically removed from those above ground by both space and time, and with nothing to aspire to, inevitably something has to give.

When Freder warns his father that the workers may overthrow him, the film was playing on the home audience’s fear of violent revolution. With Nazis and Communists fighting in the street and the Russian Revolution being only a decade old, society was in flux. Yet for all its talk of revolution, Metropolis’s politics plays it safe.

Both classes have a pair of heroes: the workers have Maria and worker 11811, and the upper classes have Freder and Josephat. The rest of classes are dealt with in broad strokes, and are both easily led by Robot Maria: the workers get so swept up in her revolutionary rhetoric they abandon the City of the Workers leaving the children behind, while Robot Maria’s sexuality is so powerful it can drive the upper classes to kill each other.

With the City of the Workers flooded, the end handshake between the lead foreman of the Workers and Joh could symbolise better conditions for workers and perhaps also a move overground, but rather than revolution there is no hint that the workers will aspire to anything more, or the upper classes will change. The mediator may have stopped Babel from falling and improved the workers living conditions but head and the hands remain unmovable.

The Whore of Babylon?

Not only did Van Harbou write the film, she frequently was hands-on in both the production and directing of many Fritz Lang films. As such her influence on the final product maybe underestimated. Her name is rightly tarnished because of her work with the Nazis but as she secretly married a man of half-Indian descent whilst living in Germany—an act that was illegal under the Nuremberg laws—what parts of the Nazi ideology she actually subscribed to is up for debate.

What is known is that she was not a member of the Nazis when she wrote the script and the politics of Metropolis seems to favour an improvement in the status quo rather then revolution. Joh Fredersen is too fallible to be a Fuhrer and the depiction of the Workers too derogatory for the film to be Communist propaganda. Some critics have singled out Rotwang as possibly being a Jewish stereotype, but this ignores the moments when we are supposed to empathise with him. If you scrunch up your eyes that pentagram on that his front door could be a Star of David, but it definitely is just a pentagram.

Where the film is revolutionary is in how it subverts the sexist trope of the female being portrayed either as a saint or a whore through the Marias. Both of them exploit societal expectations to bring down the male patriarchy.

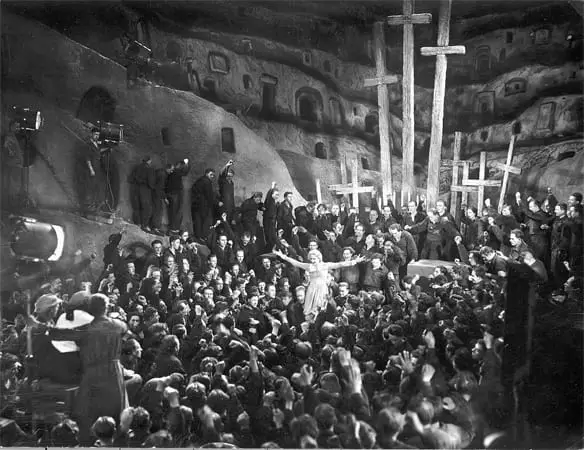

They take power from being the only female in male dominated spaces. Maria arrives in the Garden Of Eden leading a huddle of children, dressed as a peasant, telling the children that these people are their brothers and sisters. The motherless Freder falls instantly in love and starts to question his own entitlement. Robot Maria hypnotises the Workers in the catacombs with her words and body language.

Male characters show their power by their ability to touch, and by extension own women. Overground the women of Metropolis are mainly play things, hanging around the Sons Club in see-through dresses waiting to be judged suitable by Freder’s servant.

Consent is not an issue. Freder chases a flapper girl who initially refuses his kisses but after he dips her like a ballet dancer, she willingly wraps her arms around him. For worker 11811, on his first trip up to the surface disguised as Freder, the sight of a woman dressing for a night out in the cab next to him is so exotic and tempting that he is lured off mission. The male ego is so sensitive even the steel man-machine—which although shaped like a woman, has not yet been transformed into Robot Maria—is too much of a lure for Joh not to try and touch it. He is physically stopped by Rotwang who claims sole rights.

It’s this compulsion that Robot Maria exploits, turning the male gaze into a weapon. As Robot Maria’s reputation grows, she leads the upper class like a mob, but keeps her distance. She throws them a garter, and two men in the crowd fight for it until one shoots the other.

The only other significant female role is Hel, and she is dead before the narrative begins; dying in childbirth giving birth to Freder. Rotwang blames Joh for her death and creates the man-machine to bring her back.

Metropolis is seemingly built only for young women, as mothers are totally absent. This is why Maria’s maternal presence is so overwhelming for Freder. Through her influence he learns empathy, so by the time he sees Maria again he keep his hands to his side, letting Maria touch him first.

Brigette Helm’s performance as both Marias is one of cinema’s greatest. From Robot Maria’s twitchy eye when the man-machine first appears, to her devilish smile, it’s a performance of little details that make a satisfying whole. She cleverly emphasises the differences between Maria and her robotic doppelgänger through gesture. Whereas the virtuous Maria stands still at the alter and preaches open palmed, Robot Maria walks back and forth working up sections of the crowd, her back bent and arms crooked like a puppet on a string. She is Rotwang’s puppet and she often mimics a lot of his gestures.

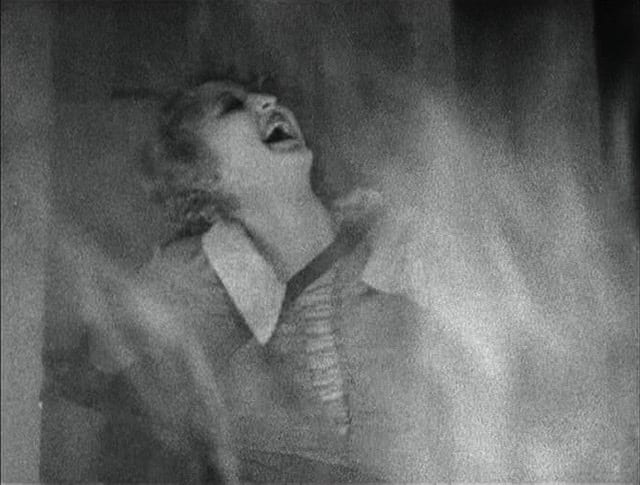

Secretly ordered by Rotwang to bring chaos, ostensibly Robot Maria is pre-programmed to be the ultimate seductress and shares his madness. When she is captured and taken to the stake to be burnt, she laughs hysterically. Her death is meaningless: she doesn’t fear the flames and revels in the madness she causes. No lesson is learnt.

The original Maria ends the film as a helpless heroine carried over the cathedral rooftops by a concussed Rotwang, who believes her to be Hel. Freder saves her and the alpha male is dominant. Yet this scene feels like post-script. It’s Robot Maria’s transgressive behaviour that makes her the most compelling character is in the movie. The image that stays with you is watching her laugh as her steel melts.

ENDE

The coming of “sound pictures” with The Jazz Singer made the score and title cards of Metropolis look old hat within months of its release, but the physical spectacle of the film still thrills 93 years on: the jagged skyscrapers with floors piled on top of each other like pizza boxes, the small cars that bustle along the Metropolis freeways, how the man-machine walks down the catwalk, the electric sparks in Rotwang’s lab. Fritz Lang’s creative team created a view of the future that is still awe inspiring.

Some things don’t date well. Freder’s early scenes are overacted, the handling of goon Thin Man is inconsistent and out of step with the rest of the cast, and Robot Maria being chased by a mob in long shot now looks like farce. But these faults are due to too much ambition rather then too little, so are forgivable.

What is most impressive is how the set pieces can still excite. The vision sequences are a triumph of design and editing. The chase through the catacombs by torchlight is unsettling, and Maria and Freder leading the children out of the flooding City of the Workers has a real physicality that only flooding a real set can give.

It is tempting to try and ignore Van Harbou’s input, given her later politics, however it’s indisputable that her experience of being a woman in a male dominated sphere shaped how she wrote the Marias. The explicit politics may be “naïve” and done in broad stokes, but it’s the sexual politics that make Metropolis socially relevant. It feels akin to Blade Runner 2049 in that it uses female robots created by men to subtly subvert stereotypes.The film was intended as a blockbuster and not a Battleship Potemkin type polemic, and this is why it feels modern.

Metropolis is a patriarchy, and although women’s rights are never explicitly invoked, the male objectification of women is the reason for its downfall. Robot Maria weaponises it, and by doing so started a tradition of cyborgs walking among us leaving death and destruction in their wake. The original saintly Maria looks a bit dull in comparison and sometimes she has to be the damsel in distress, but she does ultimately achieve her vision. In its heartless treatment of women and the workers, Metropolis is fair game for whatever chaos the Marias want to bring.