Growing up, I heard about the American Dream a lot, not so much from my parents but from media like movies and television. The American Dream was about being a success, usually self-made. In time, I believe that Dream has evolved to encapsulate what it means to be a true American. Success, usually financial, is still a part of it, but so is this idea of “us versus them.”

When did this change happen, and where did it come from?

I’m 37. In my lifetime, two events occurred that helped shape the America in which I now live: 9/11 and the advent of social media. In late 2001, a film was released that somehow managed to warn us about our current social climate. At least, that’s how I’ve managed to see it, as I’ve often revisited it over the past 20 years. Vanilla Sky is about America losing its grip on reality in favor of a comforting falsehood.

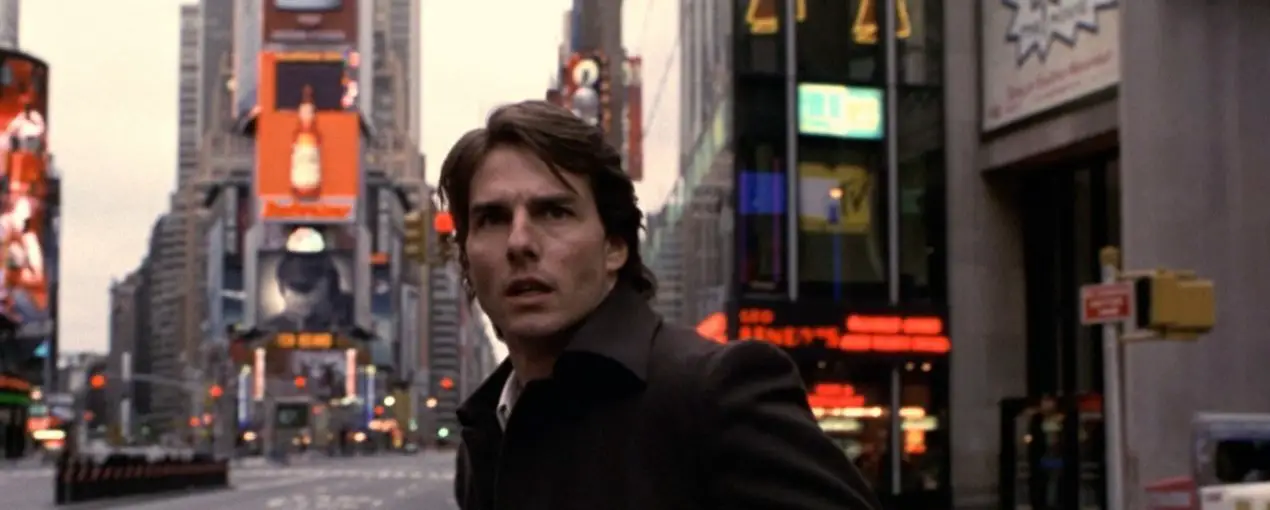

Tom Cruise plays David Aames, billionaire and owner of a successful publishing company, who wakes up one morning to a quiet New York City. He drives to work, and on the way there, he, and we, begin to realize that the streets aren’t quiet. They’re deserted. He continues on, eventually stopping his car in the middle of an empty Times Square. “What the hell is going on?” he and the audience must be asking. It turns out that David is actually having a nightmare.

Though it is never specified in the film, Vanilla Sky takes place sometime at the turn of the century, either 1999 or 2000. Writer-director Cameron Crowe’s remake of Alejandro Amenabar’s Open Your Eyes is such a time capsule of a film, representing New York (itself representing America, in as much as a remake of a Spanish film will ought to do) at a time just before 9/11.

When it premiered in theaters in 2001, just three months after 9/11, I don’t think audiences necessarily wanted what the film had. As compared to the box office of other movies released that month (the prime example being the first Lord of the Rings film), it seems audiences wanted to escape far more than introspective science fiction. Heck, even critics at the time were lukewarm toward it. Just do the usual Google search for the movie and see that it currently has a 42% on Rotten Tomatoes.

Even now, as its 20th anniversary approaches, there’s not much talk about Vanilla Sky. That’s a shame, because this is one of Cameron Crowe’s best films, and it has one of Tom Cruise’s finest performances. And I could go on and on about why I believe those two statements are true, but I want to focus on something I’ve thought a lot about over the past two decades.

The lucid dream revelation in the final stretch of Vanilla Sky is more than just a plot device. It connects directly with the opening dream sequence, as well as the film’s final moment, in order to say something about artificial comfort in modern America.

This dream at the beginning of the film, of course, is more of a nightmare. In it, David is alone in the world, which for him is not something he desires. He’s a people person. He charms his way through most of his life, spending night after night with different women and then just moving on, doing his own thing. He’s living the dream, as he tells his best friend Brian at one point early in the film. This dream means existence with other people. Without anyone, life is a nightmare for David.

David’s lucid dream is supposed to be perfect, and for a while, it is. He gets the second chance he always wanted with the so-called love of his life Sofia, and he stays best friends with Brian. However, his subconscious seems to realize the people who surround David aren’t real. As such, again, this dream becomes a nightmare.

In the end, David is given the option of resetting his lucid dream or waking up, even though 150 years have passed in the real world. He chooses to wake up, because ultimately, a real-life, even one spent alone, is better than a dream where one is surrounded by fake people. What a statement to make.

At the end of 1999 and the start of 2000, there was a sense (true or not) that we were living in an optimistic time. The economy was doing well. Crime was down compared to the start of the decade. And, in pop culture, there was a sense that we were headed to a very interesting place with movies, television, and music.

Yet here was a film, made prior to 9/11, though certainly on the heels of the 2000 U.S. election, that suggested things weren’t as great as they seemed. Perhaps, the film told us, if we bothered to look closer, we would be able to understand that the American Dream we were always told about was actually an American Nightmare.

At that time, I believed this Nightmare stemmed from an unrealistic expectation of success, financial or otherwise. Nowadays, I believe this Nightmare comes in the form of social media (though still linked with the expectation of success).

This country is filled with people like David Aames or people wanting to be like David Aames. It’s easy to say that this is because David is a successful white male who seemingly goes through life with more charm than actual talent, but there’s more to it than that. David represents all who are scared of being alone.

In the film, David is an orphan, which explains why he is both willing to distance himself from some (his one-night stands with women) and attach himself to others (Brian and Sofia). He simultaneously wants to be with people and doesn’t, because he understands that nothing lasts forever.

Except the lucid dream can last forever. And what is a “lucid dream” exactly? It’s the notion that when we dream, we can become aware of this state and thereby take control of it. The thing is, though, the lucid dream from the film isn’t supposed to make itself aware to David, which I’ll get to in a moment. In this instance, the lucid dream in the film is false, much like the so-called American Dream. In both cases, the word “dream” is attached, suggesting an unreal state.

As such, when David is confronted by his subconscious, the following statement is made to him:

“This is a revolution of the mind.”

This is spoken to David a few times in the film as a way to get David to understand that he is dreaming. Essentially, the dream world is revolting against itself, breaking down the barrier that separates itself from the dreamer.

David and the lucid dream are separate, even if it seems as if they are one. After all, it is David’s subconscious that populates and moves things along. This is how he can have whatever he desires. He’s the creator of this world, and yet when the dream begins to break down, that illusion reveals itself. Life Extension is actually the creator of this world, and they even maintain it. Because of this, David’s subconscious won’t accept this dream world and so rejects it.

Similarly, Americans, at times, are able to actually see through the illusion of the American Dream, usually when there is a breakdown of some sort, like powerful people in office getting away with immoral and unethical acts, or Facebook and Instagram literally going down for hours. It is at those times when a revolution of the mind occurs, and when that happens, we see the truth.

Ultimately, we can strive for the American Dream until it turns into a nightmare.

Or we can wake up.

In America, we strive for success, but the pursuit is never-ending, possibly because success encapsulates so much now. If we continue down this path, we open ourselves up to things like stress, health issues, lack of self-worth, and isolation. We run the continued risk of comparing our lives to the lives of others. As David says midway through the film:

“My dreams are a cruel joke. They taunt me. Even in my dreams, I’m an idiot… who knows he’s about to wake up to reality. If I could only avoid sleep. But I can’t. I try to tell myself what to dream. I try to dream that I am flying. Something free. It never works.”

If we can wake up, though, we can live our lives beyond a “dream.” As David says near the end of the film:

“I want to live a real-life… I don’t want to dream any longer.”

David needs people like we need each other. Modern society has replaced this need, though, with superficial “friends,” a la social media. This, in turn, results in a nightmare world, where the only way out is waking up, or logging off. In this sense, the lucid dream in our world consists of spaces like Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, etc. These places allow us to not feel alone, and yet we are alone. We’re isolated from one another while on these apps and web pages.

But it feels great to be with others in this virtual space of social media, even if it creates and supports herd mentality. “Us versus them” is nothing new, but it’s become ever more prevalent, whether it’s because of politics or even movies. It’s the idea of “my dream is not your dream; hence, my reality is not your reality.”

Sometimes, though, perhaps all it takes is a glitch, or one of these spaces going down for a few hours, for us to see the truth once more. That social media is the collective dream we’ve all bought into. Then again, I suppose I’m curious if America really is filled with people like David Aames. In the film’s final sequence, David literally calls out:

“I want to wake up! It’s a nightmare!”

Can we do the same? Does the collective “we” even qualify in this case? Think about all the people who take the falsehoods found in social media and then take that into the real world. For them, it’s all the same. It’s all a dream, and they don’t even realize it. So many have bought into this new American Dream to such an extent that waking up is very unlikely for them.

The rest of us, though, can see the difference sometimes. It is in these instances that we can choose to wake up from social media to reality, which is neither dream nor nightmare. It contains many of the same elements, for better or worse. The key difference is that one is true, and one is not. Of course, reality is much scarier than social media, but that’s because it’s real. I guess it’s no wonder why so many choose to stay asleep.

As we find ourselves in an America where a large portion of the population continually decides to stay in their social media dream state, it’s interesting to see how much has changed since Vanilla Sky’s release nearly 20 years ago and how much has simply morphed into a different version of the same thing.

Last year, in 2020, it was not unheard of to see an empty Times Square, thanks to COVID-19. What would a new version of Vanilla Sky need in order to suggest loneliness? Would it even need a visual metaphor, or are we past that at this point? Americans still long to be with people, but there exists actual lucid dream technology now, even if it’s not so literal.

We need not go to a place like Life Extension and pay untold amounts of money. All it takes is an internet connection and some kind of social media. Twenty years before America became the country it is now, Vanilla Sky gave us a statement that actually seems more relevant now than it did then. Ever since I saw it, though, these notions have been swirling in my mind, begging me to wake up.

Some days, I manage to. Other days, not so much. So many of us lose ourselves in the artificial comfort of the American Dream, whether it be financial success or the success of having as many followers online as possible. It’s a tough thing to wake up from because it almost feels like giving up. I mean, why not stay and fight the nightmare? Why not do what it takes to turn that back into the dream?

Except, that’s not possible, because the American Dream was never real. Some people are self-made, while most get to where they’re going with the help of others. And some stay in social media circles spewing hate, while others use social media to heal the world. It doesn’t make us any less American than the other. We’re all Americans. We just need to continually find ways to realize we’re in a nightmare and wake up.

That Vanilla Sky had ideas like these in it 20 years ago is quite something to me. Then again, it just takes time for these things to reveal themselves sometimes. Ever since I saw this film in a theater, I’ve thought about the notion of waking up, and the longer I live in this country, the more I can recognize that that idea doesn’t necessarily have to be taken literally. Writing this article has helped me understand that better.

David Aames is not a hero or a role model, but there is something to be said about watching a character go through a journey and genuinely coming out changed on the other side. It’s classic, ideal storytelling, because how often do we change so dramatically in real life? Most people like David would be fine “living the dream,” even if that meant losing loved ones. Thankfully, we have characters like David who teach by example. To get away and wake up, sometimes, you have to confront your fear and jump.

Like David, I’m unsure as to what exactly awaits us when we wake up. In the film, David isn’t waking up to life as it once was. So much time has passed, and so much will be uncertain for him as he enters reality once again. It will be difficult for David to find comfort in the real world after so much time in his lucid dream, as it is for us when we wake up from social media, but he knows that it’s so much better to live a real life.

Because the thing is, waking up does not equal giving up. It’s not about being unsuccessful or being unable to put up with the nonsense that seems to fill social media. It’s about revolution; the end of something unreal and the beginning of something real. It’s the only way we can truly live because it’s the difference between dreaming with our eyes closed and opening them to wake up, hence that final moment in the film. After all, dreams only exist when we’re asleep, not awake. Vanilla Sky tells us that no matter how appealing the dream is, it’s still just a dream.

You’re onto something, but I need to put my own dollar in.

Firstly, the American Dream originally meant: “from [literal] dirt to riches.” Meaning, one could become successful irrespective of one’s original economic station and, no less importantly, birth origin/social status. As the US was – and partly still is — a nation of immigrants, the “American Dream” was one of the legendary attractions of the country, especially for the poorest and persecuted (including prosecuted) segments of various populations of Eurasia. It became a beacon for those who struggled to feed themselves and their families. A beacon for those who struggled to survive, much less reinvent themselves. The American Dream was certainly a real thing, all the way to 20th century.

However, and I struggle to put my finger on it, but, probably after 1980s, as per the country’s published obesity statistic, it has become harder to define “success” in traditional terms of lack of war on one’s doorstep, comfortable shelter, and plentiful food for one’s own and family’s bellies. After all, it is the poorest segments of the country that have become the most morbidly obese ones. And, to worsen the situation, the American crime statistics have worsened, to the point that in some areas of this huge country “war on one’s doorstep” isn’t an exaggeration.

So, the concept of the American Dream has since evolved to become more vacuous and focused on success in a bourgeois and post-bourgeois competition. This happened, in my view because, on one hand, the definition of “success” has steadily shifted towards ever more nebulous experiences and purely reflexive consumerism (such as living in a mcmansion, owning extravagant items, and regular traveling to far flung destinations), and, on the other hand, social mobility has become ever lower after the 2000’s.

During the 2010s, labor mobility coupled with increased societal and familial alienation, mediated in large part by overreliance on media (social and regular) has made the American Dream more like an American Fantasy for the majority of those who were born into the culture of the US. After all, it is these people who have the tendency to buy said media’s values, lock, stock, and barrel.

So, now, we are way past mere bourgeois competition or consumerism and in the post-bourgeois world. People wish to compete on “influence” and virtue signaling; and they wish to do so while putting as little as possible of their own skin into it. And that, in our times, leads to name calling, needless division, as well as ever further alienation from traditionally long-term bonding structures.

Tangentially, I’d like to add that the use of “white male” in the article is an example of pointless use of a divisive term, a term that does not reflect the point of Vanilla Sky, since it is not about race. Such dogmatic terminology conveys a world of systemic oppression even where none was being even remotely intended; specifically, by the movie’s plot. Was your point an insinuation about “white male privilege?” What would be the point of making Vanilla Sky into a case about systemic white privilege? This detracts from the film’s deeper meaning and sentimental beauty.

Back to the American Dream though. For those who are long-time immigrants and have the luxury of time for reflection, like yours truly, the American Dream is more of an American pop culture anachronism, at this point. People like me realize that it once existed and elements of this Dream are both romantic and real to this day (like plentiful calories and possibilities for career advancement, if one has the talents and credentials for it).

However, many of us also realize that the American Dream neither actively says nor does anything for the preservation of precious familial and communal bonds. And it is those bonds: of obligation, of love and respect towards one’s dears – not only of one’s nuclear family, but also the extended family etc– is what makes one’s life packed with obvious and instinctive purpose. The American Dream, per se, does not directly say anything about life’s purpose, though if one really thinks thru it, it has to be implied somewhere in the background. As per Vanilla Sky, it is “the little things” that make all the difference, after all.

So, what about Vanilla Sky? I’m in my early 40s and watched Vanilla Sky more than half a life ago, back in 2001, in university. I was very impressed with the movie and have rewatched some of its scenes repeatedly since.

What do I take as its message? I take from it that it is better to focus and work on The Little Things in life – related to the real, dear people – rather than forever be stuck in an alternate reality, virtual especially. However, I do not connect the American Dream to it. Nor any politics, past or present, for that matter.

To me, it is a movie about a person who, after experiencing a serious personal setback, in the context of an otherwise comfortable, high-flying, and promising life, chooses to live in a dream instead of fighting through a — to him – intolerable emotional pain and depression. But as it turned out, when his wish materialized, being stuck in a dream, once one realizes it is a never-ending one (lucid or not), can be more intolerable than living in reality. It turned out that working on fixing reality, working on making it better was what had to be done.

The protagonist originally chose based on confusion: confusion about friendship, love, and responsibility. He chose the infantile approach of closing his eyes and pretending he was “not there,” even though real people ended up wasting their energy for nothing, suffering, missing him, and dying without his presence in their lives.

Was his decision to wake up motivated by desire to sensorily experience real life, in non-suspended state, i.e., to use the fashionable term, live life “authentically”? Was it motivated by grief, a strong impulse from realization of what transpired while he was dreaming for a whopping 150 years, and the ensuing desire to end this emulation, no matter what awaited next? To me, the answer is that he had simultaneously accepted life’s preciousness, inevitability of pain and death, and – last but not least – that, despite it all, a man has to have a destiny, via a purpose, because “every passing minute is a chance to turn it all around.”

Being stuck in an endless emulation, no matter how comforting and realistic, is pointless. “Living” eternally like that is a solipsism that becomes indistinguishable from nihilism, as the world becomes the self, and the self becomes one with this non-existent world, and both are purposeless. Neither world-to-mind nor mind-to-world operate, since the world operated upon is objectively false, and the mind is not governed by anything other than responding to synthetic stimuli for its entire existence, for however many years, perhaps even billions, for the duration of Life Extension Corp. tech’s activity in the real world. The penultimate scenes to the final “open your eyes” moment reveal that he is ready to give up this quasi-IMMORTALITY if, instead, he gains PURPOSE by actually living.

And that, along with its various touching personal scenes, my friend, is what makes this movie a truly moving and educational one. It tells us that escapism may be useful and beautiful. It might even be an inherent part of human life’s fabric, but we should not turn it into a cult by abandoning purpose or the search for it.