Before we are even given the first image, the opening moments of You Were Never Really Here set up the film’s key themes.

As the film begins we hear a protracted, and high pitched ringing, that gradually fades out to be replaced by the roar of a jet engine, finally cut off with a crunch, as if of a body hitting the pavement from a great height (foreshadowing the later death of a specific character). We then begin to hear the whispered voices of both the film’s protagonist Joe (Joaquin Phoenix) and of a young girl, Nina (Ekaterina Samsonov). Both are counting down, their voices intermingling with Joe’s laboured breathing and muttering, as he repeats the words of his father: “stand up straight, only pussies and little girls slouch” and “you must do better, you must do better”.

These sounds have been mixed with a low-pass filter, often used as cinematic shorthand for disorientation or to create the sensation of being underwater. Finally, we are given the film’s first image, a dark space, with dust particles floating through the air and the sounds of bubbles rising through water. More foreshadowing, this time of a later scene at a lake, where the motif of Joe and Nina counting down resurfaces.

From this, before a character has appeared onscreen, we know that these two people are linked somehow. There is the threat of violence, due to the brutal crunch and the threatening, claustrophobic mutters. They both feel trapped as if underwater due to the laboured breathing and low mix of sounds. This is confirmed by our second image, an extreme close up of Joe suffocating himself with a plastic bag, followed by a reverse shot of Joe as a child, confirming “I must do better, Sir.”

From its first seconds, the film has established its primary themes as an unpicking of toxic masculinity, through a character study of a man left near-suicidal by the influence of his misogynistic and authoritarian father and whose experiences are in some way linked to those of a young girl.

That You Were Never Really Here is a character study—and not directly interested in its thriller elements—is shown by its style. Fight scenes are left off-camera with plot exposition murmured, often almost drowned out by the score. As critic Judd-Porter (2018) described:

“Gone are monologues given by villains, satisfying final deaths of the big baddie, gratuitous scenes of hyperreal ultraviolence. What takes their place are scenes of genuine loneliness, of flashbacks to sources of intense childhood and wartime trauma, and an overall mood of intense and overbearing hopelessness.”

The focus is on Joe’s journey as he is pushed into a scenario where he is forced to confront the suffering of his own.

The portrayal of Joe is one of the most complicated aspects of the film. In many respects, he fits the formula for a conventional revenge thriller protagonist: a former soldier, antisocial, tortured by personal demons, working-class and out to enact revenge on besuited elites. He even does for a living what Taxi Driver’s (1976) Travis Bickle aspired to do: saving female teenagers from sex slavery. It is a common trope in some so-called ‘rescue-romance’ movies, including in You Were Never Really Here, that rapists are often financially and socially advantaged against both rescuing hero and victim.

In description, this characterization seems like a setup for a narrative propelled by the main character’s jealousy, in line with a film like Taxi Driver or the later Joker in which Phoenix also starred and to which You Were Never Really Here has been often—and usually inappropriately—compared. However, Ramsay’s film acts to subvert this archetype.

Joe is bulky, bearded and muscular, he is outwardly extremely masculine, slouching down the street with his hood up and his head down. However, when we see him privately, he becomes a very different person. In his interactions with his mother (Judith Roberts), we see him being affectionate, caring and protective. He jokes with her, pesters her for leaving messes but cleans up after her, puts her to bed and sings with her while polishing the silverware. Although he is clearly the caregiver in the relationship, his closeness to his mother suggests an infantilized character, also expressed in his diet, snacking on sweets and sugary drinks rather than the hard liquor of thriller convention. The film even throws in a couple of ironic Norman Bates references.

There is a consistent thread of Joe portrayed as almost childlike: he has a sweet tooth, he sings to himself, plays with his knife, reads lying on his stomach, tearing out pages when he is finished with them. He is devoted to his mother and childishly slurps his milkshake in the film’s oddly uplifting ending. These, as well as the nostalgic songs playing throughout the film, suggest an innocent quality, but also an arrested development. A half-recollection of an innocent childhood Joe and Nina have been denied.

This softer side is illustrated too in his interactions with Nina; in the parental manner he dries her hair and carries her on his shoulders. His behaviour is markedly different around women from around men. He seems more comfortable around women and children, while men find him hardened, violent, distant and withdrawn. As his employer, McCleary outlines his plan for a typically masculine happy ending (sailing his yacht, pointedly named Josephine II after his late wife, out through the harbour, drinking beer and eating steaks together), Joe is not even listening. He is absorbed instead in the childish activity of sorting through a bowl of jelly beans for his favourite colour. The only time he does show a sensitive side to a man is when the other man is dying. Having just mortally wounded—and thereby emasculated—him, Joe lies down beside the man, holds his hand and sings with him.

Although Joe is shown to be masochistic—as when he throws a knife at his feet or chokes himself with plastic bags—there is never implied to be a sexual dynamic to this behaviour. It is more a self-harming compulsion, a way of punishing his powerlessness and inadequacy for his failures to help himself or other victims of abuse. As a child, we see him screaming into a plastic bag out of frustration at his inability to prevent his father’s abuse of his mother, an action he continues as an adult. In many ways, he is still the child who grew up in an abusive household who has yet to properly process what happened to him. The childlike imagery used to portray him works to convey that idea, lending his character an innocence and vulnerability quite unlike most traditional heroes of the genre.

In the climax, we see this inadequacy internally exorcised rather than externally exercised through violent action, as it is in Joker or Taxi Driver. In You Were Never Really Here, it is Joe’s feeling of impotence that he must overcome, and not the impotence itself, that’s okay.

Ramsay and Phoenix foreground the idea of physical exposure as it connotes to emotional vulnerability. When Joe breaks down in tears at the end, he sinks to the bedroom floor and rips off his shirt, making him appear all the more powerless. Joe’s naked body, which features prominently in several scenes, is flabby, pink, scarred and misshapen, far from the “Hard Body” of the traditional Hollywood male.

Here his bare torso is framed surrounded with images of idealized naked women. Joe is feminized by the comparison, given vulnerability and vitality, as if one of the objects of visual pleasure that the Governor has filled his mansion with has come to life. Significantly, this feminized framing aligns Joe more with the Governor’s young female victims than the Governor himself.

Compare this to the way that, for instance, Martin Scorsese films Travis Bickle’s body in Taxi Driver:

While Scorsese’s camera plays long with Bickle’s delusions of grandeur, emphasizing his poise, strength and endurance, Ramsay depicts Joe’s strength as ungainly, brutish and tragic, and betrayed by layers of emasculating baby fat. While Travis, also a war veteran, uses an arsenal of concealed militaristic weaponry that he grafts onto his own body, Joe uses a ball-peen hammer, a blunt household tool, and one that ties into his past victimization.

You Were Never Really Here sheds the satirical adoption of masculine iconography of Taxi Driver, instead portraying a protagonist with a newfound self-awareness. Travis’s attempts to regain his militaristic pride while denying its failings are replaced by Joe’s efforts to atone for his military and familial failures. Joe never believes that he is a victim of counterculture; his error is in believing that he is not personally a victim of mainstream patriarchal culture. His greatest moment of character growth comes when removed of everything else, he finally confronts the fact that he is.

One of the key distinctions made in the depiction of Joe in You Were Never Really Here from the heroes of other dark revenge thrillers is in how the narrative mirrors his character in others. It is common for thrillers to draw comparisons between the hero and the villain, depicting them as two sides to the same coin. But in You Were Never Really Here, the picture is more complicated.

As a result of his abusive childhood, Joe often unreflectively emulates his father. He wears a towel over his face (as his father is seen doing in a flashback) and he uses a ball-peen hammer (his father’s weapon of choice) to carry out his punishment of child abusers. As he picks out the hammer at the hardware store, his eyes are fixed and glazed over as if drawn hypnotically to the weapon (although he is possibly also smiling at the irony of it, depending on how we interpret Phoenix’s performance).

Ramsay’s film suggests a fear on Joe’s part that he might be, or might become, like his father and his growth throughout the film is in large part motivated by his desire to free himself from his father’s influence.

Although he clearly struggles to escape his father’s shadow, Joe and the film’s antagonist, Governor Williams (Alessandro Nivola), are not compared at all. They never share the screen, meet or directly interact in any way, and unlike Travis Bickle, Joe does not seem to envy either Williams’ social power, his wealth or his sexual control. These are merely the trappings that allowed him to operate as an abuser, as they do his real-life headline counterparts. No, contrary to thriller convention, Joe’s main parallel is to Nina.

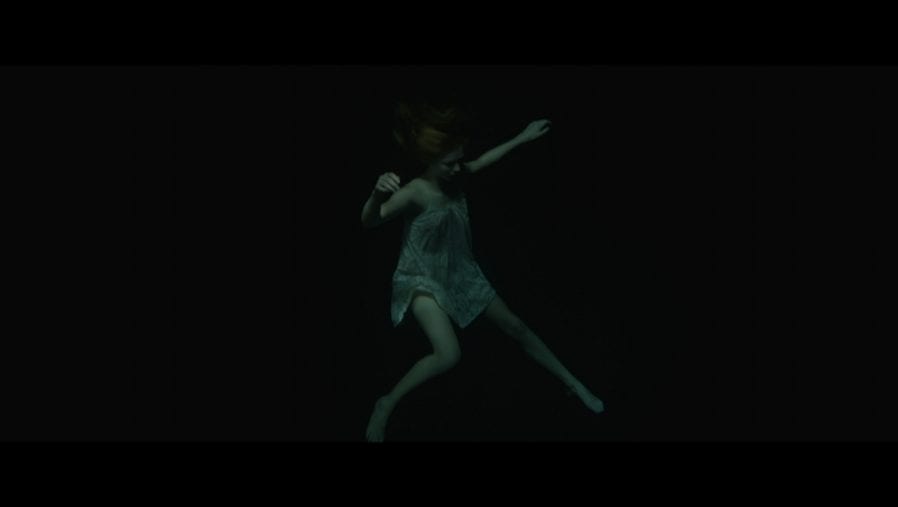

When Joe sinks his mother’s dead body (killed by the secret service) and attempts to drown himself, he has a vision of Nina drowning beside him.

This scene, foreshadowed since the opening, ties Nina both to his mother and to himself. As a child, he was unable to prevent his mother from being abused by his father, and by giving up on himself, he is—so he thinks—dooming Nina to a life of abuse. This spurs him to a final attempt to rescue her by killing Governor Williams, arriving to find that Nina has just done that herself, slicing the man’s throat with a suitably macho straight razor.

One might read Nina’s killing of Williams herself as a total subversion and disavowal of male agency in rape narratives. She is after all, functionally a prop character up until the reveal of Williams’ body, with little dialogue or agency of her own. Her killing Williams is effectively a twist, where we learn that the young girl, previously traumatized into passivity, has become as ruthless as Joe in her desire for escape. However, the picture is again more complicated than that.

It would be disingenuous to say that Nina entirely rescues herself or that because she kills Williams herself, she and Joe do not need each other. Joe provides valuable support and by killing the bodyguards, inspires her and eliminates the threats that constrained her from taking action to liberate herself. Perhaps she would not have been able to kill the Governor if she had not known that Joe was going to come for her.

This thematizing answers one of the key problems of this sort of narrative, that they can ingrain unrealistic conceptions of women escaping abuse through their inner strength. Ramsay’s film instead acknowledges that true stories of child sexual abuse are rarely wholly empowering, to quote Diane Shoos: “emphasizing the need for strength of the part of the victim, but equally acknowledging and providing for, the weakness instilled by victimhood”.

Joe and Nina’s connection is reinforced through several recurring cinematic motifs in the film. The first—established in the opening—of Joe and Nina both counting down, reappears twice later in the film: first in the scene where Joe rescues Nina from the brothel and again in the scene where the vision of Nina rescues Joe at the lake. As we later infer, it is a coping mechanism they both independently developed to help them through their abuse. There are parallel shots of them both reflected in vehicle windows, in both cases after they have emerged from a place of despair, in Nina’s case, the brothel and in Joe’s the lake.

However, the best evidence to support the link between the characters is one brief but crucial shot in the lake scene, showing Nina follow Joe as he swims to the surface. Nina’s decision to defend herself is, therefore directly tied to Joe’s decision to abandon his suicide attempt. It is through their empathy, emotional support and mutual empowerment that both Nina and Joe overcome their despair and grow throughout the film. It is through Nina’s killing of her abuser that Joe is able to exorcise the influence of his own abusive father, which he could not have done had he killed Williams himself, that would be another sublimation, not an acknowledgement.

Joe’s fears of turning into an abuser like his father are resolved by his empathy and affinity to Nina, a fellow victim. To apply Candida Yates’ writing on Taxi Driver “the underlying and continuing instability in the movie hinges upon who it is that actually needs rescuing (Yates, 2007 p.89)”. This is undoubtedly true in You Were Never Really Here and potentially more explicit than it was in Taxi Driver. However, there is also reciprocity in You Were Never Really Here, that is absent in the earlier film. Iris (Jodie Foster) did not seek her rescue and remained passive in her interactions with the narrative; Nina does not; she forms a bond with Joe that inspires them both into mutual action.

If, as described by Ryan Kelly (2018), “Cinemas of masculinity are characterized by what Freud calls the compulsion to repeat, a pattern whereby films continually reiterate and revisit without mourning traumatic events”, then what we see in You Were Never Really Here is finally an act of mourning. When Joe eventually breaks down in the film’s climax, he is relieved of his need to self-martyr in acts of rescue as Nina has rescued herself, and he is free to finally save himself from his own compulsion to relive his trauma.