At first glance, The Handmaiden (2016) may seem a crude performance of female sexuality and an ode to gendered stereotypes. But The Handmaiden is nothing if not a contradiction of first impressions. The film was developed from a 2002 Victorian crime novel, Fingersmith, written by Sarah Waters. Herself a lesbian woman, it’s not surprising that the narrative upholds an interesting and authentic reflection of female identity and sexuality. What’s more unexpected is that Park Chan-Wook succeeded so faithfully in preserving this in his 2016 film adaptation. But against expectations laid by straight, male filmmakers carelessly approaching WLW (women-loving-women) relationships, Park’s delicate exploration of cultural taboos and multi-faceted characters across his filmography stands him in good stead as a voice in queer cinema. Already a renowned director in South Korea, with hit films including Lady Vengeance (2005) and Joint Security Area (2000), Park arguably pushed his way to global recognition with the Handmaiden, which, amongst other accolades, became the first Korean film to win a BAFTA in 2018.

Full of thwarted conspiracies and unexpected twists, The Handmaiden explores the nature of patriarchal performance and possession against the backdrop of 1930s Japanese-occupied Korea. It follows the criminal scheme of Count Fujiwara (Ha Jung-woo), who sets out to defraud Lady Hideko (Kim Min-hee) by using Sook-Hee (Kim Tae-ri), a petty criminal, as his “mouse”. Sook-Hee is recruited to get close to the heiress and convince her to marry the Count so that he can steal her fortune. Following a three act structure, we are given the very intentional privilege of looking through the individual lenses of both our female protagonists. The first act, viewed through Sook-Hee’s perspective, sees her laying the foundations of a grand conspiracy that will con Lady Hideko out of her inherited fortune. The second takes the same timeline as perceived by Hideko, and exposes a counterplot to betray Sook-Hee and have her locked away. Whilst the final act presents the aftermath of the women’s decision to band together.

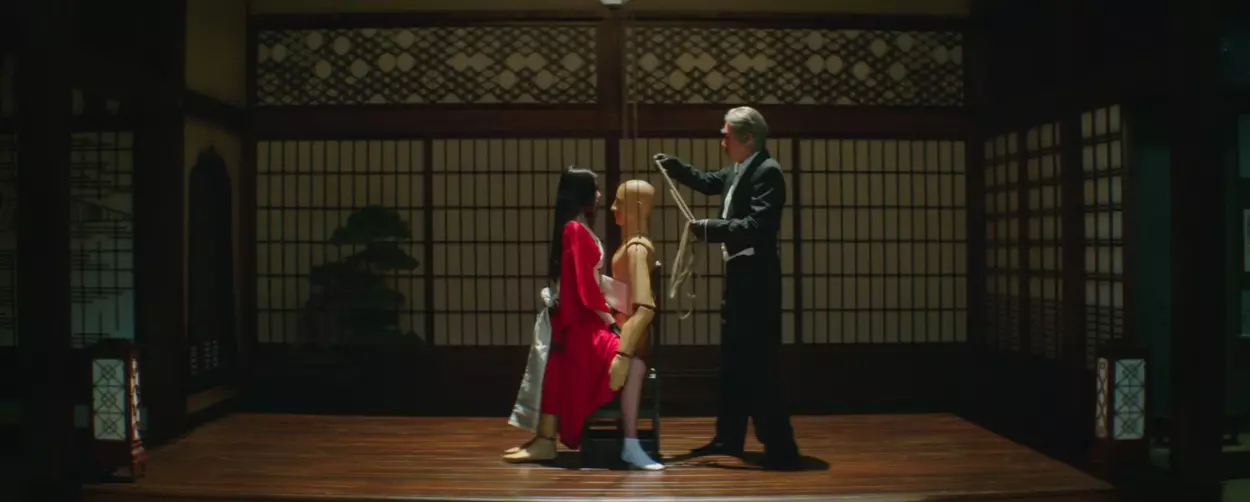

Initially, both women are blinded by the influence of the patriarchal figures who control them, and by their own internalised misogyny. Each woman views the other as “foolish and naive” and malleable to their own manipulation. Neither seems to notice the performance of naivety in the other as a learned and calculated strategy, though both exercise it. Instead, they are eager to view each other through the male gaze, specifically that of the Count, who has recruited them to defraud each other. Both women are serving as puppets, as they have done to men their entire lives, but this unique opportunity to perform patriarchal domination gives them a false sense of autonomy. As such, the two women look down on one another, conditioned by an oppressive and inferior view of women.

Though at first these tensions seem a presentation of female duplicity and competition, we later understand them as the survival mechanisms that they are. Beauvoir (1949) put it like this: “humanity is male and man defines woman not in herself but as relative to him; she is not regarded as an autonomous being”. Hideko and Sook-Hee have both suffered the loss of autonomy at the hands of men. Both orphaned as young girls and taken under the control of oppressive, patriarchal figures, they are treated like objects, recruited as pawns to be used in men’s games and indulgences. Sook-Hee must steal and deceive to make money for the Count, whilst Hideko must spend her life reading erotic novels to audiences of perverted men at the order of her Uncle (Cho Jin-woong). Both are considered instruments of patriarchy, ultimately disposable once they have fulfilled their function.

The women struggle to escape their patriarchal conditioning, which intensifies when they begin to battle with feelings of lust for one another. Just as they associate autonomy with the male gaze, so do they with desire. Sook-Hee’s initial feelings towards her mistress come out in a misogynistic impulse to possess her: “of all the things I’ve washed and dressed, has anything been this pretty? I’d like to show her to the people at home”. Whilst Hideko’s feelings mirror a similar “othering”, and her violent outbursts towards Sook-Hee and the other female servants reflect an inherited performance of patriarchal violence.

Having said this, Park is clear that these women are not passive victims, destined to repeat or succumb to their own cycles of abuse. The Handmaiden showcases the complexity of identity, and challenges our instincts to consign women to prescribed stereotypes. Hideko, in particular, presents as every female caricature, and the audience is left scrambling for which box to put her in. In the end, she is neither the docile sex object, the madwoman in the attic, nor the damsel in distress: she is an autonomous and determined survivor of abuse, and a woman with autonomy and desire in her own right. The POV camera angles and dimly-lit filming locations serve to subvert the typically fetishised topics of The Handmaiden, allowing the characters to explore their sexuality and revisit their trauma on their own terms. Just as women in the real world, they dip their toes in every trope and expectation, but in the end always masterfully disappoint.

But in order to reach this revelation, the women must transcend the patriarchal desire to control. Through calculated activities orchestrated by the Count, Sook-Hee and Hideko begin to find connection through performance, roleplaying all of the attachments that they have been denied throughout their lives. The Count tells Hideko to use Sook-Hee’s “greed she got from her mother” against her, by captivating her with clothes and jewellery. But in these moments of supposed manipulation, we see both women authentically enamoured with these representations of femininity. They use these objects of indulgence to embody dynamics that permit them to enjoy and connect to one another, playing dress-up and taking turns to play maid and lady: “ladies are the dolls of maids”, Sook-Hee observes, but both give themselves up to be dolls for the other, reminiscent of young sisters playing dress-up. Defying misogynistic associations with vanity, The Handmaiden presents women’s proclivity for objects of beauty as a tool for connection. In the dark, eerie mansion that has served as Hideko’s prison, the women decorate their interactions with flower petals, jewellery and pretty dresses. The ‘feminine touch’ is portrayed as a rightful source of liberation.

Hideko and Sook-Hee escape their realities through role-switching, using lavish clothes and luxurious bath oils as props to fulfil their shared fantasies. As Sook-Hee bathes her, she tells Hideko that she is her “baby”, much to the heiress’ delight. She innocently sucks on a lollipop that Sook-Hee has given her, and lets the handmaiden shave down her “sharp tooth” with a thimble, rubbing her finger in and out of her mouth as the camera pans down to Hideko’s breasts through Sook-Hee’s gaze. Later on, Sook-Hee expresses her desire to have breast milk so that she could “feed” the mistress. Whilst the sexual connotations of their interactions are clear, it is not sexual gratification that they seek—it is maternalism, friendship, and connection. “Is this the companionship they write about in books?” Hideko asks herself, finally realising that her draw to Sook-Hee is about more than an exertion of control.

In first sex scene between the two, Sook-Hee describes every action as a guided session on what men might expect on their wedding night: “he’ll touch you like this”, she says, and Hideko plays along: “keep doing it like the count would”. There is humour and tenderness in the contrast between their untamable lust and their detached commentary of the male gaze. Whilst this is evidence that the women are yet to escape this gaze, we see how they are using the guise of performance to find each other. Through their embodiment of male desire, they are permitted to possess and explore each other’s bodies.

The women find freedom in everything that’s been used against them: sex, performance and possession. All the while, these same notions feed the downfall of the men in the narrative. Hideko and Sook-Hee’s sex scenes bookmark their journey to liberation: once when they first begin to see each other as equals, and again once they have completed their final escape. In contrast, the men’s sexual fetishes and advances are presented as pathetic and impotent. Their pursuits of indulgence and power are posed as empty and humiliating, whilst the women’s are shown to be rooted in connection and self-empowerment. Hideko and Sook-Hee empower each other to escape from their patriarchal puppeteers, whilst the men craft their own downfall—and ultimate death—through their continued desire for power, violence, and revenge.

All of this performance at the hands of men ultimately leads the two women on a path to discovering their own autonomy, and to escaping their oppressed fates. Eventually confessing their deceit to each other, they recruit the help of Sook-Hee’s mother figure, Bok-Soon (Yong-nyeo Lee), to devise a final feminist plot against the Count. The two women escape Korea with Hideko disguised as a man, taking on the Count’s identity in a final act of retribution through the appropriation of masculinity. The film closes with the two women having sex in their room on a boat to China, where we see them using metal bells to play with each other. These same bells were used to abuse and violate Hideko when she was a child, which draws us back to the film’s prevailing motif: through a journey of self-realisation, The Handmaiden shows two women using their experience of patriarchal oppression to ultimately escape it.