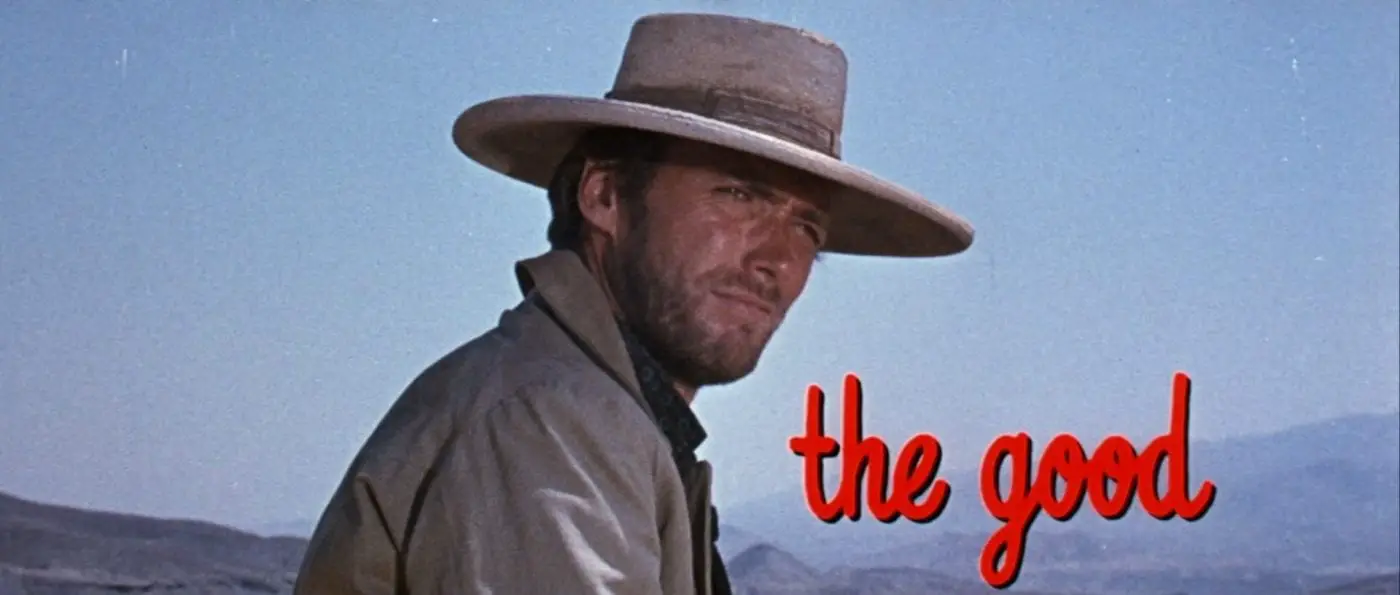

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly is tied with Once Upon a Time in the West as Sergio Leone’s greatest works. Some days, I am sure it is Once Upon a Time in the West; others, I am positive it is The Good, the Bad and the Ugly. Today, it is the latter. The Good, the Bad and the Ugly is the third and final film in Sergio Leone’s Dollars Trilogy, a loosely connected trio of films that took the Western genre and shook it all up to hell. While I have previously argued that A Fistful of Dollars is the most influential Western of the last five decades and that El Indio from For a Few Dollars More is the best villain in any of Leone’s Western pictures, I can confidently proclaim that the third film in the bunch is by far the best. It is a dizzying, supremely stylish—from the opening credits to the final shot—and altogether riveting movie that solidifies Sergio Leone and Clint Eastwood as the two most vital talents in the genre since John Wayne and John Ford got together. In my opinion, Leone and Clint prove here that they are superior to Ford and Wayne. Read on, friend, to see why.

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly is an epic Western. Not just in its running time, but in its scope and ambition, and in the details. Clint Eastwood turns in his final appearance as the Man with No Name, even though he does have a handle, Blondie; Lee Van Cleef returns, though this time as a very bad man, Angel Eyes; and the guy who steals the show, Eli Wallach, stars as Tuco. As great as Clint and Van Cleef are here, it is Wallach who turns in a performance for the ages. So hilarious, desperate, and duplicitous is his turn here, it is a great shame that Wallach was not rewarded with a little gold man. The Good, the Bad and the Ugly follows the search for Confederate gold during the American Civil War, but it is the way the characters interact and relate to one another that makes this picture such a classic. They’re all outlaws, again having a massive impact on Rockstar’s masterpiece, Red Dead Redemption 2, though some have a certain kind of moral code that dictates their actions and ultimately their success or failure.

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly is more ambitious than any of the Westerns that preceded it. It is in many ways the final word on what the Western can be. This is a coming of Jesus kind of moment: all Westerns are broken up into before and after this picture. Every movie that followed Leone’s third Western was influenced by The Good, the Bad and the Ugly. If they deny it, they’re lying. It is difficult to believe that Quentin Tarantino’s Westerns—while both excellent—could have existed without Leone’s Dollars Trilogy, but especially The Good, the Bad and the Ugly—the most confident and audacious entry in the trilogy. Leone in this picture proved that he was more than an imitator of Japanese samurai pictures or just a talented scholar. Here, he perfects his vision of the Western, and it is a knockdown, drag-out affair.

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly—in spite of its title—is less about cleanly defined moral roles and more about the blurred lines between them. As mentioned above, everyone in this film is an outlaw, whether in big or small ways. Yes, Angel Eyes is plain evil, but both Blondie and Tuco also show themselves to be capable of some pretty sadistic acts. Blondie leaves Tuco stranded in the desert, his hands bound together. Tuco walks Blondie through the desert ’til he nearly dies of thirst. Both though still pretty much like each other and do have a moral code, even if it’s skewed and off. Angel Eyes, though, is just plain rotten. He kills those who hire him, he kills those who attempt to bribe him, he kills everyone with little provocation. I argued in my last article that I believe El Indio is the best villain in Leone’s Westerns and I stand by that, but that does not mean that Angel Eyes isn’t just f***ing electric and terrifying. Lee Van Cleef proved in For a Few Dollars More that he could do good. Well, here he does bad and I mean Bad. Sergio Leone and his creative team have what I like to call Wrestling Psychology. Lee Van Cleef is a monster heel, running through everybody, to the point where you are sure that he will destroy our hero, Blondie, and our kind-of-not-but-very-likeable-hero, Tuco. But then he’s outmanoeuvred. His death does not quite rival El Indio’s last call or indeed Henry Fonda’s death in Once Upon a Time in the West, but it is still really, really damn satisfying.

The relationship between Blondie and Tuco is the reason why I have watched this film more than any other Leone picture. I just love the interplay between them. The lovely early surprise of finding out that they are working together to scam towns out of bounties is a delightful thing and subverts Clint’s reputation as the good guy, even if he is billed that way in the title. Similarly, the closing moments of the picture—where you think that Blondie is going to leave Tuco for dead, only to return right back to that relationship—are rather amusing. They kind of love each other, in a weird way, and it makes my heart sing! The scene where Blondie and Tuco kill Angel Eyes’ men together makes me whoop and cheer like Hunter S. Thompson after taking many illicit substances!

And how about that ending? The standoff is probably the most iconic scene in any Western ever made, and that is saying something when you are contending with the ending of High Noon, of the gold blown into the wind in The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, and indeed of the triumphant but melancholy return of John Wayne’s character in The Searchers. The human cost of pursuing earthly wealth at the expense of judgement in the world after is a very Western thing indeed. The death toll is high, as is the pain endured by all men involved. I love the scenes with the army Captain where the two agree to help out the cause, all the while scheming the best way to get to the gold. There may very well be a good allegory at work here, where Sergio Leone is commenting on the senseless and brutal nature of war and how what drives us is not principle or morality (as it should), but instead the prospect of earthly rewards. Clint Eastwood’s role is again subverted here, where we expect him to help out the Union army because, well, slavery was f***ing evil and so were those who tried to uphold it. Instead, he is single-minded and just wants to get that sweet, sweet gold.

So, why are Sergio Leone and Clint Eastwood the superior of John Ford and John Wayne? Well, they easily matched the epic scope and sheer charismatic power of that pairing, while also being way more switched on, as far as exploring the morality of what life in the Wild West was really like. Of course, it’s not quite as subversive as what Clint would do in High Plains Drifter, or as fair and righteous a commentary on the treatment of the Native Americans as Clint also did in The Outlaw Josey Wales, but it laid the groundwork for all that. Here, there are no heroes, just men, caught between two hard places. Kill or be killed has never been as true as it is in The Good, the Bad and the Ugly. It is no coincidence that these movies were made in the 1960s. They are in touch with the great social, political, and moral upheaval that occurred in that decade.

It is not true to reality that one would be as doggedly righteous as John Wayne was in almost every picture (provided, of course, that you accept the lie that the Native Americans were the enemy). Clint Eastwood is the most iconic Western star of the last 100 years because he was a true everyman: flawed, dangerous when pushed into a corner, and capable of doing the wrong thing for the right reasons or vice versa. He could shoot you in the back, he could steal the boots off of your feet, and yet there is something about him that makes him stand for the small human efforts to set things right after so long of them going wrong. We believe in Clint Eastwood, both inside and outside of movies, to be someone whom we look to for guidance, so powerful is his ability on-screen. (Don’t worry, we can forgive you for that Mitt Romney business, Clint. We all go a little mad sometimes.)

Before we finish, let me say a few words about the music, because it is arguably just as iconic as any of the other elements of the picture. Ennio Morricone did a lot of good work, but this is unarguably his crowning achievement. Everything in this movie is dead on, but I would argue that it is the music that is the most persuasive of the power of the artistry on display. Play this music at any point in your life and you too will feel like an outlaw gunslinger, ready to do battle at the slightest hint of disrespect. Morricone’s work is just as iconic as Bernard Herrmann’s Psycho score or the power and drive of Danny Elfman’s Batman score, and you know, probably even more so. It infuses the human with a desire to live free or die hard. It puts the viewer right smack-dab in the action. Put on the gun belt and the bandolier; you’ll need ’em.

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly may not be the single most influential Western of the last five decades (that honour goes to A Fistful of Dollars), and it may not have the best villain (that honour goes to For a Few Dollars More), but it is the best picture in the Dollars Trilogy. Its scope is formidable, its power, its emotional resonance, and its uncanny style and flair cement this film as perhaps the single greatest Western ever made. Sergio Leone crafted this masterpiece in such a fashion that it will live for as long as there are movies and humans to watch them. If for some batshit crazy reason you have never seen The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, I hope this piece has somewhat convinced you of the folly of that decision.