When you confront the title of Sam Raimi’s 1995 western tribute The Quick and the Dead, you are met with foreboding biblical allusions. Referencing 2 Timothy 4:1 and 1 Peter 4:5, the heavy crux of those descriptors is God’s judgment. Plenty of westerns over the history of cinema have called down the thunder of fate and punishment for their protagonists and antagonists. Normally, the engine of judgment runs on the quality of each opponent’s aim. But this is Sam Raimi, the audacious man behind The Evil Dead and Army of Darkness. That pulp specialist took the doom-and-gloom revenge western and made it downright frisky 25 years ago.

The many synonyms of “playful” describe the shine given to every dusty crease of The Quick and the Dead, from boot heels to gun muzzles. Written by Simon Moore (Under Suspicion, Traffic) as an homage to the spaghetti westerns of Sergio Leone, it would take uncredited on-set rewrites from John Sayles and an unofficial doctoring from Joss Whedon to add the right amount of gloss that would play right into Raimi’s strengths. At the time, The Quick and the Dead was another haughty cactus in the arid multiplex desert released during a decade-long glut of westerns riding the coattails of Unforgiven. The entertainment quotient keeps this stylish romp above its peers.

Thanks to the overbooking of locations during that ’90s saturation, the Old Tucson lot in Arizona became the canvas for the fictional town of Redemption. Production designer Patrizia von Brandenstein (Amadeus, The Untouchables, Ragtime) gives this one-street town of dreary denizens flair beyond tumbleweeds. The townspeople are controlled by the wealthy outlaw John Herod, played by the second-billed Gene Hackman. His decadent mansion and roof-mounted sniper squad tower over the weak, who cannot usurp his power. Every year, Herod gives the people a glimmer of a chance to take him down by hosting a quick-draw tournament.

The annual affair dangles that challenge, coaxing contestants with a hefty $123,000 cash prize. The event brings assassins, frontier celebrities, opportunists, hired guns, and hardasses with itchy trigger fingers to Redemption. Each arrives at the local watering hole run by Horace (Pat Hingle) to announce their presence and throw their hats into the lucrative ring. Gaudy introductions highlight a studly array of daring pistoleros, and Raimi passes around the spotlight for the arriving talents to sound off, putting all the egos and danger in one place for several perky scenes.

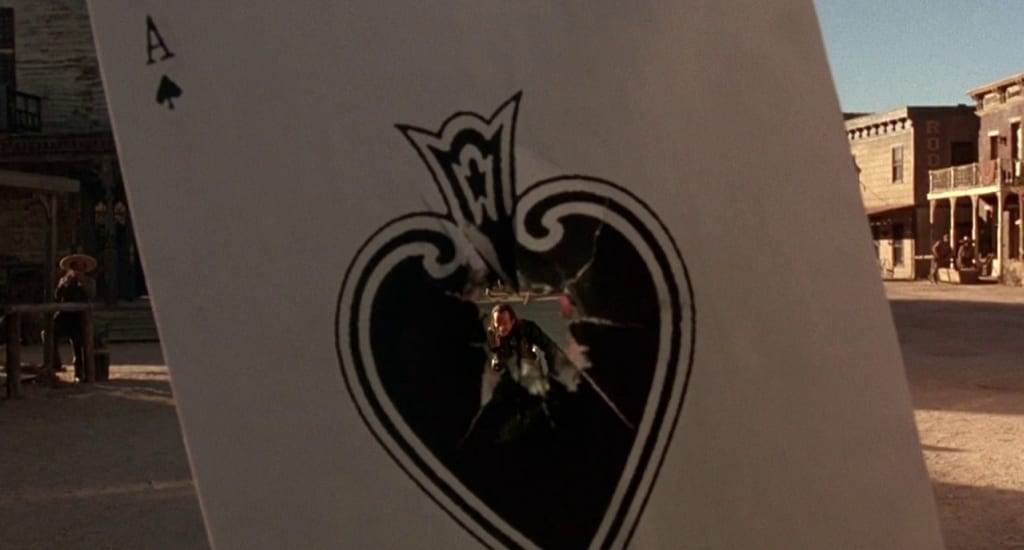

Lance Henriksen, with his black attire and mustache-combing vanity, is Ace Hanlon, flipping off horseback to shoot playing card targets (a stunt Lance practiced and performed himself). Keith David is Sgt. Clay Cantrell, pulling drags from his enormous pipe with educated cultivation. Decadence like theirs is matched by ex-cons and two-bit thief types played by Mark Boone Junior, Kevin Conway, and Tobin Bell. No one sounds or looks the same versus other such movies, with their faceless opponents lacking personalities. This is a battle royal of personality. Costume designer Judianna Makovsky (Pleasantville) gives them unique, character-defining looks which are all you need to spot the proverbial white hats from black.

A few contestants stand out thanks to their recognizable charisma. With a wide smile and a great big ego stands The Kid, Herod’s own illegitimate son, played by a pre-Titanic Leonardo DiCaprio, who would love nothing more than to earn proper respect and replace his old man. Tossed into town shackled and pious is Cort, a former posse mate of Herod’s and now a man of the cloth, played by Russell Crowe in his American debut. The last entrant is the boldest: the top-lining Sharon Stone leads as the sharpshooting and mysterious (gasp) woman nicknamed Lady, who has Herod in her crosshairs as revenge for a prior family tragedy.

The frolic begins when this dynamite cast is called to grit their teeth, gloat, and glare with firearms in their hands underneath the hat brims and duster jackets. The script produces a bevy of tough-talk quotes that curve the corners of your mouth in a dastardly way to match the performances. The snappy accents and voices of Henriksen, Davis, and others would alone make this movie a terrific radio play, even before their aforementioned bold looks and statures. All are having fun with little snippets of character notes, making big impacts with very little.

Fans are right to point to the twin stardom springboards in this flick, both of which were handpicked by Sharon Stone. DiCaprio, whose salary was paid by the actress out of her own pocket, brings a smirking gaiety, and Russell Crowe adds a needed layer of stoicism in a film of mostly vile-vs.-vile. Legend has it that Sam Rockwell auditioned for Leo’s role after Matt Damon turned it down. Likewise, Crowe was a virtual unknown, whereas Raimi initially favored his Darkman lead, Liam Neeson. My, what could have been?

While each member of the ensemble drips with their own measure of merry menace, no one tops the great Gene Hackman, who was 65 at the time and enjoying his senior peak. When he admonishes DiCaprio in one of those tough-talk quotes, “I’m not sick or old, and you’re not half the man I am,” that’s the master actor talking, too. There is never a wasted movement or expression with the two-time Oscar winner. His signature snicker and grinning, evil cackle that caps his line deliveries never get old. Find the Old West nickname for “clinic,” and that’s Hackman’s strut in this movie.

Hackman looms large, but The Quick and the Dead is still Sharon Stone’s star vehicle. The then-36-year-old (in the same year as her Casino Oscar nomination) plays Lady as dry as the Mojave soaking up the preening rain of all the chauvinism around her. Contrary to the Hollywood tendency to force a romance, her Lady pushes back all three potential suitors with a dismissive and steely resolve to keep the character tough. Raimi and company even cut a love scene with Crowe’s Cort (someone Stone later labeled as her favorite on-screen kisser) to strengthen that, and it was a wise choice. For better or worse, Stone is the least animated of the cast. Her sorrowful backstory flashbacks involving her character’s marshal father (an extended cameo from Gary Sinise) are the biggest swerves that take audiences away from the appealing action.

Luckily, there is action to spare. Where the playfulness of The Quick and the Dead really zings is with the collected filmmaking craft on display. There are 11 gunfights in this movie, and all were intentionally staged and shot differently despite having the same basic objective. One secret MVP of the film was gun coach and weapons master Thell Reed, a real-life fast-draw professional who put the actors through three months of training and used nothing except period-authentic firearms. The results really show, with the performers drawing from their own holsters with skill and speed. When the countdowns and showdowns are upon us, amid the blowing horns and soaring strings of western veteran Alan Silvestri’s assertive score, the created anticipation and tension are outstanding. We see and believe the actors are there twirling their pistols and pulling their own triggers, instead of stuntmen.

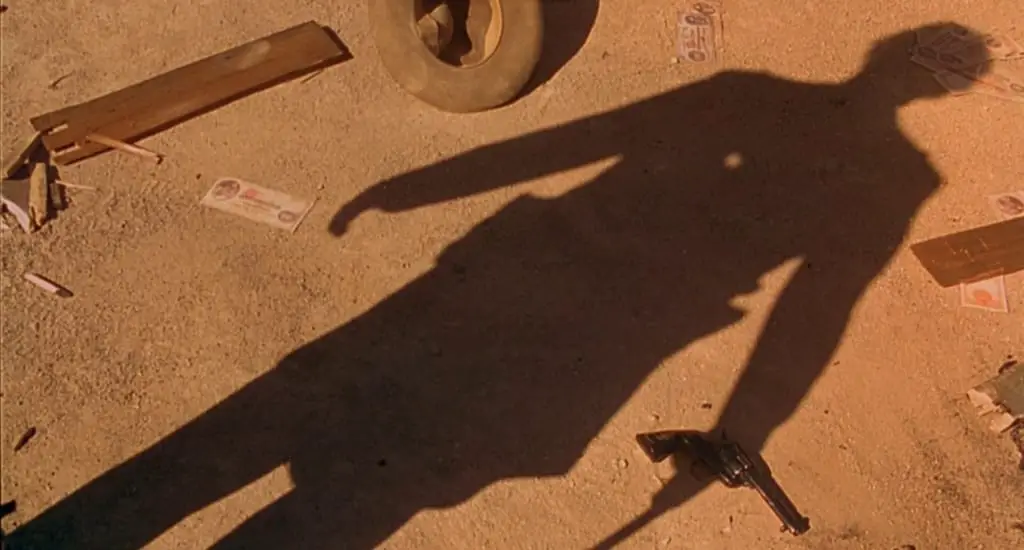

Sam Raimi surrounds his sense of pulp with true professionals getting the chance to inject more high-spirited style into the western tropes. The dynamite combination of cinematographer Dante Spinotti (Heat, L.A. Confidential) and two-time Oscar-winning editor Pietro Scalia (JFK, Black Hawk Down) is responsible for much of that whirling excitement. Spinotti plays with every camera tool in the shed. Split-diopter shots merge depth and perspective across long sets. The variations of movement from crash-zoom closeups and shifty rolls come from all angles. Raimi has a blast with framing and perspective through various structures (and body parts) as holes for light and shadow. Scalia gives those tricks a roller coaster effect of speed between rapid cuts, slow-motion montages, and dissolving transitions that would all make a comic book tip its hat.

Speaking of comic books, the whip-cracker turning this deadly game into a playground of punchy luridness is future Spider-Man trilogy helmer Raimi. The man is a genre master, and his prior horror roots give The Quick and the Dead the right violent edge beyond the waggishness of its overall feel. Like the gunfighters waiting for the clock to strike, Raimi hits his viewers with eye-opening suddenness. Plenty of westerns get their jolts and kicks from hollering and shooting their rounds into the air. Raimi knows putting a bullet through your adversary is far more enticing.