My favorite part of watching as many movies as I possibly can is that you are always left open to experiencing something that resonates with you like you did not imagine possible. I had read a brief synopsis of Hirokazu Kore-eda’s 2004 film Nobody Knows but I did not anticipate the film to tap into the documentarian parts of my childhood. A 30-day free trial of Hulu had me trying to find the best little gems of the service before time ran out. I had recently seen Kore-eda’s 2018 film Shoplifters, and while I was not as enamored with it as the rest of the film circle, I was enchanted by his glimpses of deep humanism in the struggles of the everyday.

It is those small details that keep me fixed in international cinema because there is an attention paid to the profoundness in the mundane that most American filmmakers seem unable to appreciate or even recognize. It is the look on the face of someone much too young who knows that without some quick thinking neither them nor their siblings will eat tonight that allows us to really see ourselves in the other than it is the act of leaving the home and executing the plan to make money. It is the gentle exploration of lower-depth realism Kore-eda implores that made the world pay attention in Shoplifters and made me pay attention to Nobody Knows.

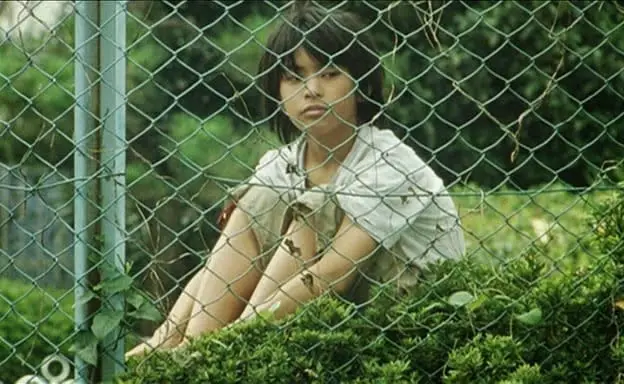

Nobody Knows finds Koreeda firmly in his element—the film is a family drama where 12-year-old Akira manages his family’s small Tokyo apartment whenever his loving, yet unreliable mother engages in another one of her disappearing acts. Akira lives in the apartment with his three siblings, the existence of all of them except Akira, hidden from their landlord. Clearly no stranger to his mother’s neglect, Akira knows exactly what to do when he reads the latest note leaving him in charge of the apartment and his siblings with the help of only a little money wrapped within the paper. You can sense the realization in the eyes of the older children, their journey through their own world that they long ago created has resumed. They have been abandoned, yet they long for their mother, they have made their own rules yet are in desperate need of an endearing authority figure, they relish their independence yet crave their fully formed family. The juxtaposition of wants and desires, of expectations and reality, of independence and adolescence, have created a world in which nobody knows.

Kore-eda takes the world building power of cinema and turns it on its head. He does not just create a world that these siblings know; he creates a currency, a network, a language, and an understanding that can only be understood by those who have lived the experience. Based on a true story, Kore-eda is somehow able to tap into the experience which necessitates taking care of yourself to survive while being drastically ill-equipped in years. He is able to deeply understand what it’s like for a child who should be taken care of, to be doing the caretaking. He can film the intricacies of someone who is suddenly and often charged with taking on the role of head of household when what they really want to be doing is playing video games. Akira’s life is so much different than the two boys he brings over to play. At first, the boys love going to his house—there are no parents home, no limitations on what to eat and win, and no one to tell them to stop playing the video games they spend all night playing. The freedom the boys feel is quickly abandoned when the reality of a home with no adults sets in. When the kids run out of food and the house begins to smell because they can no longer afford to pay for trash removal, Akira’s new friends swiftly become his old friends as they vow to stop going to his house to play.

What Kore-eda also is able to deftly communicate through Nobody Knows is the network children create between themselves in order to survive a lifestyle with no adults. These siblings are all one another has, and in the absence of a parent, the oldest becomes the one in charge despite needing nurturing himself. The story centers around Akira and his attempts to traverse the position his mother put him in. Kore-eda explores what it is like to exhaust your too few resources and be left in a situation that you have nothing left for yourself or your siblings. The desperation you feel is palpable but still inside of you is the desire to make life easier for the children in your care and hope that at least some of the realities that you had to deal with can escape their concern.

At one point in the film, Akira pulls some money from the minimal allotment he has to feed and clothe everyone and keep the house running, and give some to each of his siblings as a present “from” their mother. He wants them to be saved from the realization that their mother has abandoned them and is not taking care of them, he wants them to think she is still thinking of them and sending essentials their way despite her absence. Within this network, the children, Akira’s younger siblings are, in fact, spared their reality but the oldest sister under his care has become aware of the situation they are in. She gives her money from “their mother” back to Akira to make his load a little easier and to do her part to take care of the family. The children also have created jobs for each other to participate in to keep the house running (as well as possible anyway with four children under 12 living with no adult supervision) and to fill up their days as none of them can go to school with their mother gone. They are each the most stable force in the lives of each other; therefore, integral to love and support throughout the actuality they must endure.

I did not expect to connect so much to Nobody Knows before seeing it, but the reality is that my own childhood does not look that different from Akira’s. I too had a mother who would suddenly vanish for unidentified periods of time, sometimes leaving a little money behind and some checks to use to pay the bills, and sometimes not. Like the kids in the film, I didn’t have a father to help shoulder the burden, either. I didn’t have someone to talk me through why I had to grow up so fast while simultaneously feeling the weight of abandonment that only coming home from school to a note and a little money to last for who knows how long brings about. I didn’t realize until about a year ago—the first time that I truly had my heart broken—how much that pain I’ve buried yet carried around and adds an immense weight to my life and relationships. I thought I had escaped my childhood. I graduated from college, went to grad school, bought a house, had two kids and a stable job. I have lots of friends, I try to help everyone out that I can, I eat well, I exercise, I volunteer, everything around me is always clean, and my bank account always has emergency money in it. I had crossed so many items off the list of what makes a successful person that I honestly thought I overcame the childhood I came out of.

It wasn’t until I was going to therapy to help get over that terrible relationship I had (When Movies Are Your Therapy) that I realized that so much of the way I am is a byproduct of the continuous unpredictability of the life of my formative years. It took a breakthrough in my therapist’s office to realize that I kept going to school so I could constantly forge connections, that I bought a house to give myself a sense of stability, that I had kids so I would never be alone, that I kept a job I hated so I would know that I could always pay the bills, that I’m so helpful because I believe that I have to earn the love of others since the only people that were supposed to love me left me, that I eat well and meal prep on Sundays so I know there is food in the refrigerator for the whole week, that I exercise to try to clear my mind of the continually running to-do list I repeat in my head, that I volunteer to build more connections and to make amends that the life I came from didn’t put me in a worse off position that others, that I keep everything neat and organized to ground myself from the constant upheaval I went through as a child, and that I compulsively don’t let my bank account dip below a certain number to avoid the financial stress I went through as a child. I really had to wrestle with the idea that the childhood I had created these behaviors that, on their face, seem like positive attributes of a person, but that are fueled by a dark reality.

In addition to the above mess of personality features, I am also rarely shaken by unexpected events. My closest friends think of me as the friend group’s “crisis manager” because I am rarely unnerved. Here again, however, is a trait that seems positive on its face but informed by so much negativity. Not much gets me off my game because I had to deal with an electrical fire on my own when I was eight, and a broken window in the middle of a snowstorm when I was 11. I accidentally locked myself in the utility room of my house while doing laundry one time that my mom had been gone for 22 days—I always kept track—and in any of those aforementioned incidents panic was not going to lead to anything productive. Like Akira, I had to think of a way to get to the store, to get money, to take care of a house, and to keep it all together somehow. There was no time then for me to begrudge my lot in life or to wish for anything to be different because I was too busy just surviving each day.

To me, that is the most amazing thing about Nobody Knows, that Kore-eda is somehow able to show the psyche of the children in the film. The amount of which must be normalized to be able to keep moving forward is something anyone in that situation can relate to, and anyone outside of that situation will think disingenuous. It took me watching this film with another person to really hit me how much I related to this film because it told “a day in the life” of how I used to live. Where he saw situations too unbelievable to employ the suspension of disbelief required to enjoy a film, I was nodding in agreement for having done something quite similar as a means to make it through another day.

I hope Nobody Knows this version of the secret life of children. I hope Nobody Knows this level of abandonment, pain, and neglect, and I hope Nobody Knows how real the events depicted onscreen are. The farther away we get from the ground, the harder it is to remember the struggles of the young. I hope Nobody Knows the devolution that takes place onscreen as we watch four young people being robbed of their innocence and carefree years. I hope Nobody Knows the subtlety of expression that accompanies a life filled with moments and situations that are bigger than you, but yet, left for you to handle. I hope Nobody Knows the zen-like calm than becomes part of you when your daily life becomes one filled with so many problems and complications that can only be answered with a measured and relaxed response. I hope Nobody Knows what it is like to pretend that everything is okay as a means to escape the reality one is trapped in or to be so preoccupied with issues of survival that nothing fazes you. The reality is, however, that this film is based on a true story and that I sat nodding my head in understanding during its runtime so it is clear that too many know what this life is like, despite how much we may wish that Nobody Knows.