With successful—if controversial—poetry, novels, and screenplays completed, in 1969 Pier Paolo Pasolini returned to the medium of film as director with Medea, his adaptation of the tale of the betrayal of Medea by Jason, based on Euripedes’ play, and starring opera singer Maria Callas. Desirous of its sensuality, the motion picture became a way for Pasolini to materially express a philosophical and sacral reality, however personal.

Poetry contributed a deep literary acumen which Pasolini consciously lived through political realities. He matures at a time when Italy had become a darling of capitalist prerogatives, resulting in what he deemed a “cultural genocide” in the import of consumerism. He mourned the casualties—the decimation of cultural diversity and expression—especially in the depletion of bucolic lifestyles still prevalent in rural Italy at the time. His depth comes from facing his life as a gay, subversive film-philosopher head-on, intimately intertwined within the lives of sub-proletarians in streets. It would ultimately cost him his life on November 2, 1975.

Poet-cum-Auteur Pasolini got his start in the movies working as a writer on Federico Fellini’s 1957 Nights of Cabiria. Medea, adapted from Euripides’ 431 BCE tragedy of the same name, is Pasolini’s 12th film. By 1969, the Italian auteur had taken on Oedipus Rex (1967), auto-poetically processing Freud’s mythic love for mother and disdain for father (who was, in Pasolini’s case, a straight-up Fascist in Musolini’s military).

Both Pasolini and Euripides were poet goths uncovering and probing power’s underbelly, creatives rubbing shoulders with the philosophers of their day. Euripides subverts the crowd’s expectations, portraying the marginalized of Athenian society in depth as humans with their own agency–assertive women, virtuous slaves, civilized barbarians. Likewise, Pasolini breaks convention in the history of film adaptation to opt for a conjured realism, drawing insights from archeology and anthropological study which took flight during the late 19th and early 20th century. Intelligentsia’s recluses, the poets’ paths–like Parmenides’ before them–intertwine with Hers.

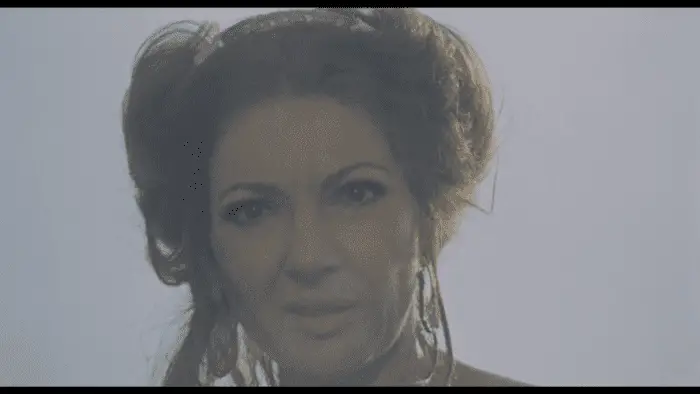

Maria Callas is cast in her first film role after decades of film as prima donna supreme: Medea inhabits Callas on the operatic stage from 1953 onward. She, too, subverted the norm. Lambasted initially for her “ugly” voice, Callas’ resonant timbre stirred her audience out of indifference. Critics eventually came around. At and on all stages, Maria Callas was brilliant—and unlucky in love. Before the name Onassis became associated for most folks as “Kennedy-Onassis” with the remarriage of widow Jackie Kennedy, Aristotle Onassis disingenuously courted Callas: stringing her along, siphoning money, time, and passions, for years. Medea is also Giuseppe Gentile’s acting debut as Jason—he was an Italian Olympic medalist. Given this perfect symmetry of personas matching the characters they meant to play, I can only say: touché, Padre Paolo.

The Gospel According to Matthew, Oedipus Rex, and Medea started a trend of films that re-examined elements of well-established and institutionalized religions and myths in function of their representations of marginalized lower-class peoples, their ritualistic aspects, and their utopian and revolutionary potential–triggered and enhanced by sex and violence. (Mathijs and Sexton 138)

Medea hearkens to Pre-Socratic, archaic Greece, illustrating gestalts of historic crimes in which Reason and Order—the prioritization of logos—banished the mysterious sacred. The scope of the film explores terrain well beyond that laid out by Euripides’ tragedy but present in other ancient sources. As in his adaptation of Sophocles’ Rex, Pasolini knows “an image can have an allusive force equivalent to that of a word,” allowing the text to shine by omitting much of the play’s own contents as such, letting Medea speak in depth visually. “It is one of his main skills as a director that he[…] does not need words to express his characters’ thoughts” (Macdonald 29).

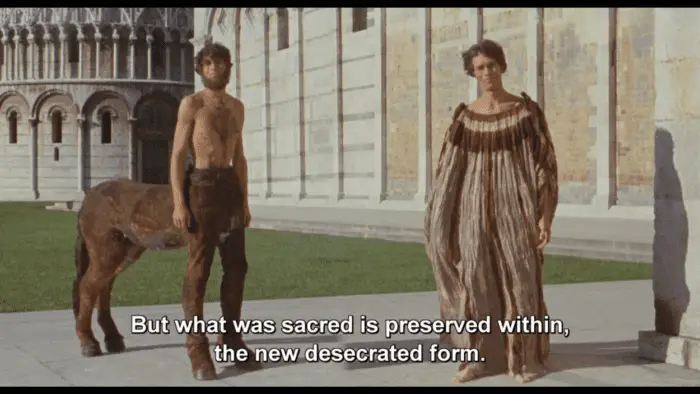

The film opens with the Centaur, Chiron (Laurent Terzieff), lecturing a growing child Diomedes/Jason (Gentile). He chides, “All is sacred, all is sacred, all is sacred!” eventually taking on human form as Jason’s body grows. The young would-be hero is “no longer concerned with the seed and its mysteries.”

Enter Otherness contra Order. In Medea’s Colchis (shot in Turkey’s Cappadocia), at the edge of the known world, feats of Barbarian magic manifest Frazerian fertility sacrifices. Divine, cosmic, and philosophical “reason unlike our own” color Colchian culture. Meanwhile, Medea’s soundtrack supplants the a-rational tone with the chants, bells, and exotic instrumentation courtesy of Tibetan monks. We are elsewhere, transported to a world not yet conquered by written word or the arche of absolute time. In breaking the boundaries of the play to elucidate strands of the myth’s backstory from elsewhere, Pasolini plumbs depths made possible by his enormous knowledge of myth, affinity for mystical religious practice, and taste for the tragic flaws of our time.

For some, nothing could be so horrifying as Medea’s decision to murder her own children. They miss the point, as ever. To understand Pasolini’s Medea, we need to unpack some of the ancient and archaic baggage condensed into its 110-minute runtime.

“If both civilized Athens and the heavenly gods protect Medea, how can we make sense of the world?” bemoans Richard Rutherford (48), who earlier informs us of Euripides’ tendencies to render the unexpected for the dominator culture: “women behave manfully, slaves show nobility and virtue, barbarians express civilized sentiments” (xxiii). Men such as he tend to idealize the Heroic. Legends of the Argo and Jason’s seafaring adventures precede Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey (Graves 586), giving us a window into the archaic Greece depicted in the film. It’s important for us to consider the conditions under which these heroes were produced—and by what means they prospered—before throwing shade or condemnation Medea’s way.

Robert Graves sketches the terrain in his magisterial The Greek Myths. The time is 1100 B.C.E., the thrall of the Bronze Age. An alliance of patriarchal tribes—one worshiping Heracles, another Apollo, and “men of all tribes” under the aegis of Demeter—spew into the surroundings from central Greece (576). The Doric invasion is only one of a plague of similar such activities as fraternal warring males tearing through the countryside: raping, pillaging, capturing, burning towns to the ground, driving their inhabitants to the edge of civilization, and so on. This we see from the perspective of the Argonauts as they set out for Colchis on a somewhat less idealized Argo; an oversized raft will do for Pasolini.

Burgeoning archeological research originally developed in the 1950s—Marija Gimbutas’ kurgan hypothesis—argued that against distributed federations of peaceable and matrilineal (not “matriarchal”) cultures, Indo-European invaders (now called the Yamnaya culture) began their millennia-long spree from the steppes north of the Black and Caspian Sea (modern-day Russia):

The former cultural border lines disintegrated, the great Old European art and architectural traditions vanished or deteriorated; the religion and social structure changed. The horse, the wagon, the yoke, the dagger and spear, the patriarchy, and new gods and mythical images (typical of Indo-European mythologies) were introduced or imposed. (Gimbutas 131)

Despite Gimbutas’ acumen—reading comprehension in 20+ languages, acting as translator to Harvard scholars at a time that women still needed male escorts to access the libraries, and as a thorough, scholarly archeologist—following her death in 1994, she becomes the test-case for how not to do the job. Because of her attempt to elucidate pre-Indo-European conditions in Europe, she is dismissed as having made wild, unsupported claims of “primitive matriarchy;” which she did not do, and did not use that word. (For cultures deemed “primitive,” see Graeber & Wengrow’s The Dawn of Everything [2021]). Colchis hardly looks like “matriarchy”—however, it may well faithfully reconstruct how a matrilineal, archaic culture in that time and place may have appeared.

The essence of Gimbutas’ assertion has not only been validated, but deepened. The discipline of archeology is in the throes of a new revolution in archaeogenetics—with the ability to bear our her claims, and then some. What we now know is that this activity was not only the source of the exhaustive spread of Indo-European languages—which seeded everything from Sanskrit, to English, to Persian, to ancient Greek—but also the spread of particular genetic lines. In some cases, this resulted in a complete genetic replacement of populations; at least, where the Y-chromosome is concerned. Stated differently, invaders hailing ultimately from a culture based in the steppes, wielding chariots, horses, and deadly weaponry (including bands of violent male youths), descend on peaceable cultures. According to some interpretations of the genetic evidence, they murder all the males and take females as their prize, a tactic which overcomes cultures in their worst iterations (c.f. Sanday [1981]). Whatever happened, the Bronze Age, and its production of Heroes, was the source of a massive genetic bottleneck reserved specifically for male lines of transmission. Its spread was as vast as these languages.

The contours of the original mythic content bears witness to this process as imaginatively experienced on the coast of the Black Sea in the modern-day Republic of Georgia. Jason, aided by Medea, steals the Golden Fleece. The majority of Medea’s depictions of these events passes in silence, much as they pass in our moment; for now, at least. Stricken by Eros at the behest of patriarchy’s greatest ally, Hera, Medea betrays family and homeland to serve the desires of Her would-be captor. Could this allude to a mythos still driving current events, or at least hearken to the stealing of some form of substantive knowledge, given the Golden Fleece’s afterlife as a Masonic (fraternal) totem? Advanced metallurgy, perhaps, or something about…time?

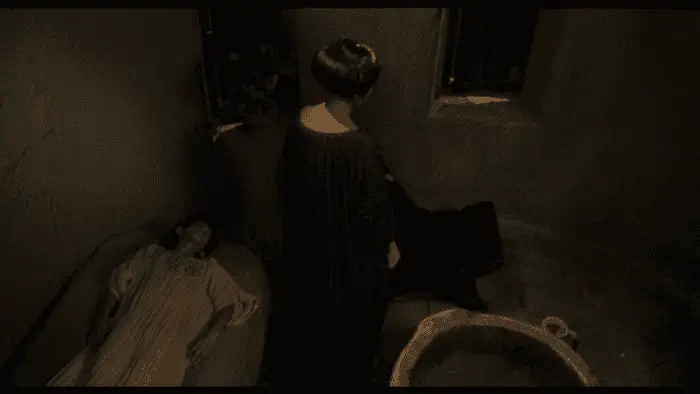

Jason begrudgingly accepts marriage as a compromise to achieve his ends. As a sacrament, marriage extends well beyond written sources. Monogamous marriage likely developed in the Neolithic, along with more sedentary agrarian lifestyles, resulting in what scholars call the Neolithic Demographic Transition (NDT)—a shorthand for population explosion. If the science is any guide, this event falls well before the development of “star clusters,” overzealous men and the many children they produced with multiple mates. But Medea has awoken; She is not only wife and mother. “I’m still what I once was—a vessel bearing experience not mine,” Medea announces to Her Nurse (Annamaria Chio) who well knows the deep well of Medea’s magic. (I shivered when I watched it this time, knowing what I know now.)

Euripides’ original tragedy, and Pasolini’s adaptation, puts agency back on the table for our heroine. As She snaps out of her weeping to churn into the planning stages for the demise of Her unfaithful, emotionally impoverished, opportunistic husband, She paces to and fro with her Chorus who are not yet brave enough to stand for themselves. How can they, when even in our own time, millennia later, contemporary choruses of women are weighed down by succeeding generations of Patriarchs—Scalias, Kavanaughs and Thomases in the Supreme Court? Trumps in the Presidency? Weinsteins running Hollywood? No matter, She will do this for them. For maximum suffering, better to murder those he loves most and revel in the sight of Jason dying on the inside. Even better: decrease instances of R1a and R1b haplogroups.

It’s truly amazing what a little knowledge has the power to do in this world. Perhaps we can move on from the plagues of these cultures, and the contemporary white supremacy they ultimately inform. We can, and should, replace them.

Cited

Gimbutas, Marija. “The three waves of the Kurgan people into Old Europe, 4500-2500 B.C.” Archives suisses d’anthropologie generale, Geneve, 43, 2, 1979. 113-137.

Graves, Robert. The Greek Myths. (Penguin Books: 2012 [1957]).

Euripides. Medea and Other Plays. trans. John Davie with notes by Richard Rutherford. (Penguin Books: 2003).

Mathijs & Sexton, Cult Cinema. (Wiley-Blackwell: 2011).

Pasolini quoted in Susan Macdonald’s “Pasolini: Rebellion, Art and a New Society,” Screen 10:19-34 (1969). pp. 25. Op. cit.

Additional References

Audiovisual:

Callas. dir. Tony Palmer (1978) featured in Medea. dir. Pier Paolo Pasolini (1969). Blu-ray, 2011.

“Introduction to Pasolini’s ‘Medea’ (1969).” Panel discussion. New York University, September 28, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HwZlgLsF2yU

Medea. dir. Pier Paolo Pasolini (1969). Blu-ray, 2011.

Text:

Anthony, David W. The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World. (Princeton, 2010).

Graeber, David and David Wengrow. The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity. (Picador, 2021).

Mallory, J.P. In Search of the Indo-Europeans: Language, Archeology and Myth. (Thames and Hudson: 1994 [1989]).

Sanday, Peggy Reeves. Female Power and Male Dominance: On the Origins of Sexual Inequality. (Cambridge University Press, 1981).