For those that experienced life under the cruel regimes of governments such as the fascists of World War II, those traumatic experience are greatly magnified through the art produced as a result of the endured suffering. Just as Pablo Picasso’s painting Guernica intensifies the atrocities committed by the fascist government of Spain against civilian resistance, Pier Paolo Pasolini highlights the utter depravity of humanity through the actions of the fascist Italian government against its citizens in his iconic controversial film Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom (1975). With lengthy dialogue-heavy scenes where the fascists explain their cruelty and numerous scenes of extreme explicit content, Pasolini showcases the evil of humanity and its tendency to kill and brutalize innocence as a whole.

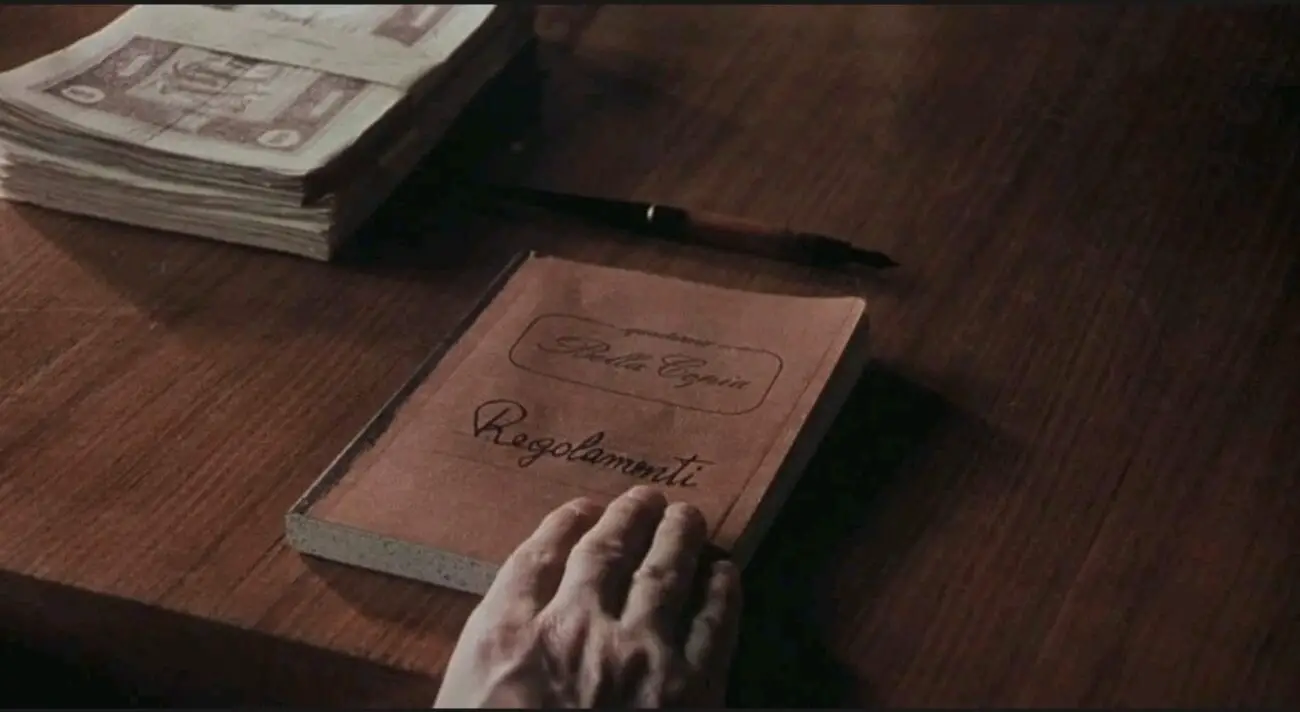

At the beginning of the film, the audience is shown four libertine men sitting together at a table and negotiating terms for an event of torture and sexual assault. These men are The Duke (Paolo Bonacelli), The Bishop (Giorgio Cataldi), The Magistrate (Umberto Paolo Quintavalle), and The President (Aldo Valleti). As they converse with each other, they choose four male guards, four male studs, and ten young boys and girls to be kidnapped from a nearby village to be the victims of extreme physical and sexual violence. This scene of negotiation highlights the lack of any empathy or compassion held by typical fascist governments as these central libertine figures view the acts or orchestrating large-scale kidnappings and torture through the most businesslike viewpoint possible. This scene also highlights the danger of rationalizing evil acts through intellectualism as they spout ideals held by philosophers such as Freidrich Nietzsche, distancing themselves from their horrible actions through the fragile lens of acting out true human nature, instead of willing forces that have their own agency to not commit such heinous acts in the first place. Pasolini also uses these titles of duke, magistrate, bishop, and president to show the potential for oppression against common people that can be held by such influential figures in society, as they hold the most influence in citizens lives due to their spheres of wealth, law, religion, and federalism being present in day-to-day functions of industrialized nations. Furthermore, Pasolini’s highlights the inherent impunity held to such positions of power as they’re able to orchestrate events of criminality while there’s no reasonable method for innocent civilians to resist them due to their massive sway over a country’s functions.

As the film works as an adaptation of the Marquis De Sade’s original novel The 120 Days of Sodom and Dante Alighieri’s Inferno, Pasolini is able to expertly shift the timeframe of Sade’s late 1700s novel to Italy in 1944 while utilizing the circle divisions of Aligheri’s work into dividing acts within the film. These changes enhance the overall quality of the film as its ability to utilize Sade’s twisted narrative features into a commentary on the actions of a real-world government and setting makes the content more provoking compared to its fictional counterpart, while the divisions of Aligheri’s work is used to show the descent into suffering felt by the kidnapped victims and make the fate more tragic. While exploitation and controversial filmmakers forgo any sense of style or technique to focus purely on the sufferings present in their films, Pasolini instead uses his strengths as a director to make the film appealing in a filmmaking and design sense to intensify the scenes of rape and torture. Through the use of static camera shots and detailed set design, Pasolini immerses the audience into the lavish setting of a massive mansion with wide and well-furnished rooms, while the static camera shots bring out a painting-like aspect to the film’s images as all the detail in a scene is able to be highlighted effectively due to it not being cut around frequently. However, the beautiful sets deliberately contrast against the brutal actions taken against the young boys and girls against the screen, while the actions are further reinforced due to the camera being focused on it at all times. Furthermore, Ennio Morricone’s lavish score further contrasts the audio and visual sufferings within the film, making the film a pair of both decadence and depravity.

After the intro sequence where the libertine figureheads orchestrate the massive kidnapping in the Republic of Salò, the dehumanizing nature of the film’s plot begins to start. As all the boys and girls of a nearby village are lined up and stripped naked before being taken away to the mansion location, they’re judged on the base physique in an almost pageant manner. In another scene later in the film, all the captive boys and girls are told to bend over and cover the genitals as the libertine characters decide which hidden figure in the group has the most visually appealing posterior, with the winner being condemned to death. These scenes of physical inspection and observation bring a clinical nature to sex and nudity, juxtaposing Pasolini’s previously made series Trilogy of Life, where the films had a jovial and innocent outlook on nudity and sex compared to the brutal and disgusting portrayal of sex and nudity in Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom. The libertine characters also use sex as an aspect of control as they and their “studs” constantly rape and molest the individuals in multiple scenes throughout the film. The positions of power between the older characters and the young captives are visually present in their drastic physical difference as the guards and libertines are both taller and stronger than their victims, while the guards and libertines are armed with weapons while the victims are defenseless, further reinforcing the exploitative nature of fascists against everyday citizens.

Pasolini further shows the exploitation of the citizens by fascist governments during the “Circle of Shit” sequence of the film. Signora Maggi (Elsa De Giorgi) tells a story that involved the death of her mother, causing one of the young girl victims to wail as a result of her own mother’s death and begging for mercy by God, invoking anger from the libertine characters based on their rules of non-religious worship, which will bring death to those who break it. As a result, The Duke defecates on the floor in front of the young girl and demands her to eat it with a spoon, eventually leading to all of the individuals having a feast involving fecal matter in a dining area. This scene is the ultimate statement of innocence being attacked as the young girls and boys are forced to partake in the most violating and disgusting act imaginable along with their captors, who surprisingly seem unfazed by eating faeces compared to their victims. While the fascists enjoy the disgusting act, their control over their young victims to become involved without their consent underlines the lack of agency people have compared to a governmental faction. This scene, just like the others, is also shot in extreme visual detail with numerous close-up shots and the camera focusing on individuals biting into (fake but near-realistic) faeces, bringing a sickening quality for the audience.

In the “Circle of Blood”, the film rapidly closes to a brutal finale. With all the young victims exposing rule-breakers to their captors to avoid their eventual demise and the deaths of a male collaborator and servant girl due to having a forbidden sexual encounter, the film ends on the condemned boys and girls dying in excruciating methods of scalping and cut-off tongues while only a few survive due to their obedience with the fascist captors. These scenes of violence are shown through a first-person point of view as the libertines observe through binoculars in an upper window into a courtyard where the victims are killed. This becomes the most immersive point of the film as the audience looks through the same binoculars that the evil fascist characters hold to their face, making the audience complicit in their viewing of depravity as much as the fascists are complicit in organizing and enjoying the horrendous events. And while the outside world watched the deaths of millions during World War II before being involved, the depravity present in such cruel governments never goes away as the world still continues to watch heinous actions from a distance just like the characters at the end of the film.