The middle of the 20th Century saw the worldwide proliferation of new national cinemas. Characterised as new wave movements, and typified by blending cinéma verité, neorealist, and often surrealist aesthetics, such cinemas reflected the changing attitudes of the time, with latent existential intellectualism and countercultural romanticism. Italy delivered the films of Fellini and Antonioni, France Godard and Truffaut, England Lester, Anderson and Russell, and America the new leading lights of Hollywood such as Ford Coppola and Scorsese, still regarded as titans of the cinematic landscape. However, one such auteur, considered their equal at the time, has fallen by the wayside in the decades since, his films neglected and often forgotten. This being Arthur Penn, who delivered the world iconic, revolutionary and intellectual works like Bonnie and Clyde and Alice’s Restaurant. Penn is hardly alone in going underappreciated or in his flame diminishing over time, but his canon is still uncommonly strong and richly deserves reappraisal.

The Miracle Worker (1962)

Penn first broke through in the early 1960s with one of his most conventional, though far from least powerful of successful works, The Miracle Worker. Arguably director Arthur Penn’s most mainstream film, The Miracle Worker is the closest he has come to producing a conventional Hollywood drama. This may even be argued as one of the films that defined the term Oscar-bait, as it ticks a lot of the requisite boxes: an inspirational true story with strong theatrical performances and big emotional swells. However, it is still recognisably an Arthur Penn film, with his intelligence, verve and ferocity intact.

The film follows the attempt by Anne O’Sullivan, a governess, to find a way to educate her charge, a child named Helen Keller, who was left deaf and blind by a case of scarlet fever as an infant. It’s an absolutely hysterical film with nearly every line delivered at a shout and many scenes almost free of dialogue, the story instead told through violence as Sullivan and Keller do battle over getting Keller to eat with a spoon or learn to sign.

The actors absolutely hurl themselves into these scenes and the physical performances from leads Anne Bancroft and Patty Duke really are extraordinary, even if Bancroft’s Irish accent isn’t convincing for a second. Frankly neither are the Southern accents of the supporting cast (Keller was raised on a plantation in the Deep South in the 19th century) but it sort of works. The accents are just another respect in which the film is completely unhinged. It’s an absolutely exhilarating film to watch, with the emotions at such a consistently high pitch. The film is made up entirely of scenes that if taken in isolation would seem to be the climaxes of any other film.

If there’s one word to summarise this film it’s passion; every piece of its educational themes and delivery is enthused by absolute, unwavering conviction and certainty. It’s rare to see a film so defiantly and resolutely confident, and protagonist Anne perfectly embodies that righteousness. Maria von Trapp and Mary Poppins wouldn’t have lasted a day.

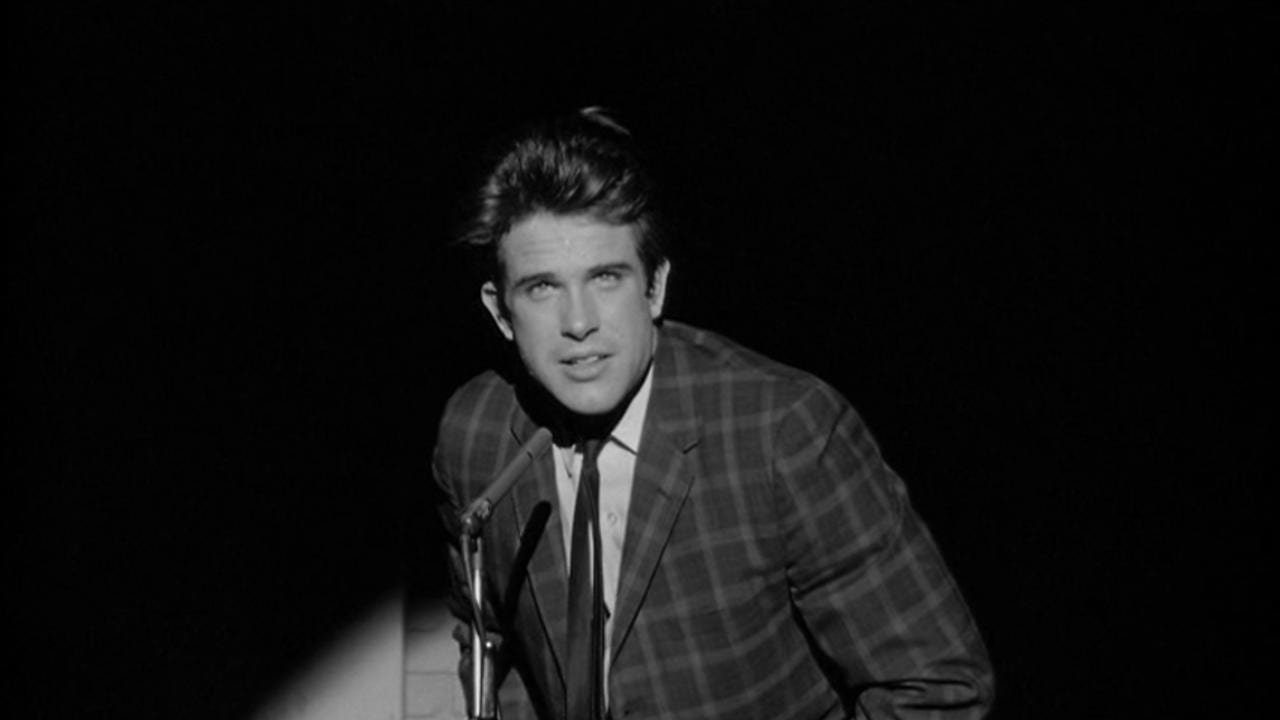

Mickey One (1965)

As a filmmaker, Arthur Penn spent much of his career retelling narratives of characters paralyzed by indecision, fighting forces too vast and powerful to be properly comprehended, never mind overcome. We’ll see many later examples of this, but perhaps no other of his films, for better or worse, more acutely articulates this struggle than Mickey One. It may be, in my opinion the weakest film in his canon, but it’s nonetheless a fascinating conundrum.

“Mickey One” is the name given to our main character when he steals the Social Security card of a Polish man whose name his temporary employers find too taxing to pronounce. He is a nightclub comic who awakes from a reverie of revelries to discover he has run up inconceivable sums of debt to the mob, whom he learns intends to keep him working for them in perpetuity until his infinite debt is paid. Rather than succumb to such an existence, he runs, hopping a train car, but soon finding the nightclub circuit calling to him. It’s in this state of transitory, Kafkaesque not-quite existence that ‘Mickey’ spends the film, in constant hesitation. He’s not so much on the run, but always one foot out of the door.

This setup allows the film to touch on many different themes. Religion is a recurring background element, with the quizzical line ‘is there any word from the lord?’ a leitmotif for the film. However, the most prominent theme, to which almost every single moment of the film ties back, is the horrifying existentialist impression that Mickey, and indeed all of us, are rats in capitalism’s maze.

Mickey’s whole life is comprised of things, things he once fleetingly possessed on credit and must now pay the interest on. He owes everything and yet has nothing but his wits and his legs carrying him ever forward, into another compromise, another exposure, from which he runs, for they carry with them the latent, unnameable threat, of what? Servitude? Or erasure?

Being made by artists, it’s no coincidence that both this and its later transatlantic cousin O Lucky Man! should come up with the same answer to this existential nightmare: retreating into one’s art, accepting the compromises of social living, and trying to make the best one can of it. In the hopes that one day, you might be as strong as the best of us: those who can slip free from the bonds of their childish possessions and maintain their innocent grace. As the film’s one truly free character, Kamatari Fujiwara’s nameless, destitute street artist, has done. Drifting loosely and silently through the narrative, salvaging scrap, the detritus of capitalism, to make his own artistic statement.

This statement is the antithesis of Mickey’s neurotic paralysis. The work the artist exhibits, and names simply: ‘Yes!’ is a Heath Robinson-style parody of industrialisation in three dimensions, with seemingly no purpose but to destroy itself. It embraces its own transitory and self-destructive nature, in order to exist for one beautifully nonsensical moment.

Mickey One the film does not achieve this level of transcendent beauty. Despite its aspirations to a freewheeling joie de création, it is, perhaps appropriately, too weighted down by its own self-shackled form. Its New Wave Brechtian playfulness ultimately caps its effect and leaves it feeling more like a cinematic essay than a truly moving piece of art itself.

The Chase (1966)

Arthur Penn saw more artistic success with his next film, even if the critics of the era didn’t recognise it. 1966’s grueling sociological thriller The Chase is possibly my favourite Arthur Penn film. There may be some respects to do with race in which the film is bothersome, but for an American film, set in Texas and made in 1966, it has its head screwed on remarkably straight. Critics at the time declared its histrionics unrealistic, which is a) not the point, and b) not the case. It’s as savage and angry a film and as close to a horror film as Arthur Penn ever made (with the possible exception of Mickey One).

The film, in a narrative that calls to mind everything from traditional biblical epics to Zorba the Greek, Darren Aronofsky’s mother!, Dostoevsky’s Demons, Nemes’ Sunset, Akira, Inherit the Wind, High Noon, Short Cuts, Cool Hand Luke, No Way Out, Do the Right Thing, and To Kill a Mockingbird, tells the story of a small Texan town’s descent into chaos when a convict breaks out of jail. The film follows, among many others, the Sheriff (Marlon Brando) as he tries to get the escapee (Robert Redford) to turn himself in, while the rest of the dissolute town drinks themselves into a lynch mob over the course of a long Saturday night.

The resulting narrative culminates in one of the most tense and unsettling “end-of-second-acts” I’ve ever seen, as minor characters are devolved into detestable villains through their mutual empowerment of one another’s monstrosity. The script and direction are sharp and alive in a way that made me appreciate the recent Assassination Nation a lot more, it may have barely achieved what it set out to do, but it’s rare that films that dangerous come along these days. But I suppose it was also rare then too.

It’s a brutal dismantling of the American myth of idealism’s triumph over evil and a venomous indictment of mob mentality that is rich with detail and tension. Brando’s Sheriff Calder is another of Penn’s hopeless idealists, whose attempts at de-escalation fall on deaf and drunken ears as the rule of law collapses and the small town descends into pandemonium. Penn may have articulated these ideas a year later with Bonnie and Clyde, but here he approaches the subject from the perspective of law and order and its desperate attempts to keep reason and trust alive, and this is not a film to be missed by any means.

Bonnie and Clyde (1967)

Dejected with law and order and its social contract to reign in the mob, Penn determined to form a mob of his own, equally doomed to failure, with Bonnie and Clyde. There are many films that follow the ‘boy and girl on a cross country crime spree’ premise, some wonderful (True Romance/Gun Crazy) some reprehensible (Badlands) and others a little of both (Natural Born Killers), but there can be little doubt that Bonnie and Clyde is the definitive and one of the most important American films ever made.

The film mythologises the story of Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow, two outlaws who became folk heroes in the depression ravaged 1930s, when banks were fair game for public retribution. Clyde is a charismatic but impotent rogue and Bonnie a bored young woman emotionally trapped by the day-to-day grind, and in one another, and the retinue of followers they accrue, they find a willfully self-destructive form of ascendancy.

However, despite the potency of their eulogistic myth-making it’s the sheer weight of their mortality that Penn impresses upon you. As long as the mob exists to put down rebels, the legendary rogues are anything but immortal. In Arthur Penn’s hands, their story becomes a fascinating re-purposing of the outlaw hero of American legend, a savagely anti-authoritarian polemic and the true birth of the new Hollywood movement. American cinema came of age with the release and success of this film, stepped out of the shackles of the Hayes code, studio systems and McCarthyist censure to find a new richness, to explore the full power of cinema as a righteous tool of political attack.

With most films that demand respect for the ground they broke, the film itself is a distant curiosity, examined and probed rather than seen. In some ways this is true of Bonnie and Clyde, but Penn knew cinema and how to manage it and wield it to create something that is not pleasant or enjoyable or reassuring, but something that is innately powerful. It is neither one of the best films I’ve ever seen, nor certainly one of my favourites, but it is unquestionably one of the greatest.

Later works

After the success of Bonnie and Clyde though, Arthur Penn seemed incapable, or was perhaps simply unwilling, to keep the attentions of American audiences, with his best films of the era only receiving their just deserts in the rotation of home releasing. His 1975 film Night Moves, fits firmly into the mid-’70s, revisionist take on the film noir, with a similarly human, more difficult and nihilistic bent as a product of America’s post-Kennedy assassination, post-Watergate counter-culture. Gene Hackman plays a very Hackman role as a private detective dispatched to the Florida Keys to bring home the daughter of a washed-up actor, who undergoes a crisis in a similar fashion to James Mason’s lead in Sidney Lumet’s equally underrated The Deadly Affair, throwing himself into his work after discovering his wife’s infidelity.

The film stays a fairly conventional, if more adult and melancholy than usual, film noir, that is until its final minutes with an extraordinary, surreal final reveal that leaves you with a sense of the “who killed the chauffeur” nihilistic potential of the arbitrariness of the genre. Hackman gives another strong performance and the supporting cast (including before they were famous James Woods and Melanie Griffith) are characterful and human. There are some analysis-worthy motifs like a line about seeing Bobby Kennedy’s assassination and how on TV it seemed like it was underwater, that take on new meaning as the film ends and add an allegorical layer to the films’ dark cynicism. Once again, Arthur Penn seems to be articulating a frustrated and crushing sense of despair at the political dissolution of his times.

This attitude continued into his later work, his formerly spry and idealistic heroes became drabber, more downhearted, and more compromised. Warren Beatty gave way to less glamorous and more externally conflicted stars such as Gene Hackman and Jack Nicholson, who starred in his uncanny revisionist Western The Missouri Breaks.

The Western genre as it was previously known, effectively died in 1962 with The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, but was quickly resurrected by the wave of Spaghetti Westerns in the mid-’60s that were effectively Samurai movies translated to a western setting. After that, the genre began to be used by new Hollywood filmmakers as an arena to breed darker and more mature

subversions of its Americana iconography, and so was a natural fit for Penn, seeking an outsider community where his idealistic rebels could simply live in peace.

The film follows a gang of horse rustlers led by a forlorn Jack Nicholson as, like the Hole in the Wall Gang and The Wild Bunch, they find themselves driven to ground by a new breed of lawman, this time in the form of a mercurial regulator played with feverish and demoniac joviality by Marlon Brando. Although extremely well played by the cast—especially the colourful Brando who gives arguably the most extraordinary performance of his career—and Penn’s directing is typically raw and freewheeling, the film is held together by a fantastic script, rich with ambiguity, character, nuance and a pervasive sense of both melancholia and increasingly fleeting joy.

The rebellious spirit of the ’60s was slowly dying in Arthur Penn’s films, as it was everywhere, and this middle-aged bourgeois compromise found voice in his last great film, his lyrical odyssey of Americana, Four Friends. The film follows Danilo (Craig Wasson), who starts the film arriving in America from Yugoslavia, a child full of idealistic promise and belief in the American dream. From high-school, through college and beyond, we follow his search for his mercurial high-school sweetheart Georgia, but more directly, for some distilled essence of America itself, of a place he might call home and not find his hopes and dreams shot down at take-off.

Years pass by in a flurry and before he knows it, his ambitions have drifted off in the current and his world has grown smaller. It’s an unsettling and eerie journey through a man’s life, with many devastating disappointments, shocks and tragedies along the way. Yet, Four Friends still emerges as Arthur Penn’s most sentimental, tender and oddly uplifting work, and acts as a reflective note of resolution and contentment after a career filled with expressions of angst and torment.

That’s an amazing list of fantastic movies for sure. And I agree, how could you leave our little big man??

LITTLE BIG MAN, Penn’s picaresque but powerful anti-Vietnam war epic—based on a revisionist Western novel whose heroes are Native American—merits prominent mention here. Cavalry attack on the Indian village (to the incongruous fifes-and-drums of “Gary Owen”) remains an iconic and chilling indictment of “Manifest Destiny” and the subjugation of indigenous cultures.