“Who the hell owns that dog?” – Fred Madison (Bill Pullman), Lost Highway (1997)

“My dog barks some.” – O.O. Spool (Jack Nance), Wild at Heart (1990)

In his seminal essay Zur Genealogie der Moral (1872, On the Genealogy of Morality), the German philosopher Friederich Nietzsche writes at great length about morals and the so-called ascetic ideals. Trying to describe the ascetic philosophy, Nietzsche uses an analogy of dogs in the basement – where those who try to live in accordance with the ascetic ideals of poverty, humility and chastity often take the “dogs” and place them in the basement, hoping to silence the dogs and believing that they live peacefully in the cellar without “hostile barking and shaggy rancune” (Nietzsche 2007 [1872]: 78). In doing so, however, the well-meaning people often end up creating a pressure-cooker-like situation where the dogs gnaw at each other and become increasingly aggressive or even perverted.

That analogy, I will argue, is interesting and potentially useful when exploring the films of David Lynchs. Films in which we often hear barking dogs, people who talk about dogs, bark like dogs and act like ferocious, wild animals. Lynch’s films are full of animalistic noises, and they often feature sounds and images that illustrate the primal urges and fantasies of different characters. Animalistic behaviors or sounds can occur without warning as if to illustrate the inability within the main character to repress or constrain his/her predatory nature, and manipulated animal sounds can illustrate the dogs in the basement – the things that our main character has hidden or tried to silence.

In this essay, I will look at that particular aspect of Lynch’s work, delving into different scenes and sequences from his scant filmography. Tentatively, I argue that there are (at least) three different levels of animalistic sounds and behavior in the works of David Lynch:

- animalistic sounds that illustrate the predatory side of a human being during a violent act or when a character recalls his predatory actions;

- animalistic noises and imagery used in a more general sense to illustrate the dogs in the basement, i.e. the primal urges and fantasies within a given character or in society as a whole;

- characters that bark or sound like wild animals as if to illustrate the total, if only momentary, loss of control.

From Animals to Human Beings: The Grandmother and The Elephant Man

The first and perhaps most explicit example of this animalistic motif and sound design is seen in the 34-minute long short film The Grandmother (1970), which is an abstract story, yet more narrative and explainable in nature than David Lynch’s previous short films. In this film we meet four characters, simply called boy, mother, father and grandmother, in as much as we never hear their actual names, nor have any traditional dialogue in film. The mother and father talk to their son, it seems, or rather they yell and bark at him while proceeding to either beat him or pet him (in a disturbingly sexual manner). The son’s name might be Matt (or something similar), but it is virtually unintelligible, and the cries of his parents sound more like generic barking than like any specific name. Given that we see the parents crawling on all fours while sounding like sniffing and barking dogs, it is also more than likely that we are meant to notice their likeness to animals before ever understanding their actual words.

The animalistic sounds illustrate the primal and uncontrollable actions of the two parents – the father seemingly barking at his son while correcting him, and the mother sounding like a whimpering dog while caressing and pulling at her son in a strangely sexual fashion. The libidinal and destructive urges, which we usually keep down or silence, are heard on the soundtrack, and the use of extreme close-ups and unnaturalistic colors also serve to de-humanize the parents or to illustrate their animalistic side.

Fig. 1-4: The parents crawl on all fours and make whimpering and barking sounds like wild dogs, but, ironically, they discipline their son by sticking his face in his own urine stain on the mattress. Frame series: The Grandmother (1970).

Ironically, the parents are angry with their son because he has a habit of wetting his bed, it seems, and their way of disciplining their son is eerily reminiscent of humans trying to teach a young dog not to wet the carpet. This, too, I suspect, is a typically Lynchian point: We should always look beyond the obvious. In other words: The son’s actions, which we might often connect with dogs, result in reactions from his parents that are far more animalistic and far less civilized. This irony is reminiscent of The Elephant Man (1980), where the main character, John Merrick, is likened to an elephant, but where Merrick is, in fact, the most humane and civilized of all the different characters. “I am not an animal,” as he famously says, “I am a human being.”

Similar scenes can be found in Twin Peaks (ABC, 1990-1991), where Bobby (Dana Ashbrook) and Mike (Gary Hershberger) bark at James Hurley (James Hurley) in the jail cell, and in Twin Peaks: The Return (Showtime, 2017) where we have some more surreal instances of people barking and sounding like wild animals both in the woods and in the prison cell.

In relation to the jail scene from the beginning of the original series, Gary Hershberger has once told me that it came “out of the blue.” It was not scripted, nor was it explained by David Lynch, and Hershberger and Ashbrook did not know what the intention of the barking was, but they naturally thought that the sounds were meant to illustrate the animalistic, bully-like behavior from the two football players. As Hershberger puts it:

David said, “Gary, have you ever been to the zoo?” “Yeah,” I said. “Well, do you know that there are monkeys that bark at each other in a very angry way? I want you to do that.” I just said “Okay,” but I didn’t know what he was getting at until I saw the final scene which is both funny and slightly scary at the same time. Often in Twin Peaks, we have these competing moods and themes, and we don’t exactly know how to process or deal with it. (Halskov 2015a)

In Twin Peaks: The Return, the alcoholic, barking man, played by Jay Aaseng, might be nothing more than a drunk (as the character name would have us believe), but the sheer surrealism and strangeness of the scenes might also lead us to believe that those scenes are part of a fantasy or dream space or even an alternate reality. In both cases, the barking sounds would seem to serve a clear purpose, either by pointing to the unrestrained and uncivilized nature of an alcoholic man (who, by drinking, is less capable of keeping his dogs in the basement) or by cueing a transition from one narrative plane to another.

The Bark of Repression

In other David Lynch films, where dogs and animal sounds play a less outspoken role, they might still serve a clear function in specific scenes and sequences. In Eraserhead (1977), for example, we hear a barking dog during the surreal dinner sequence where Henry (Jack Nance) meets his mother in law (who makes strange passes at him) and where he gets a headache akin to Pete’s headaches and nosebleeds in Lost Highway (1997). Here, the barking dog seems to add to the general chaos and surrealism of the scene, reminding us of the reality (of fatherhood) that Henry is seemingly trying to repress.

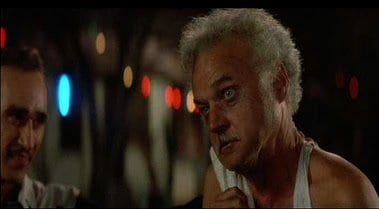

Similarly, Lost Highway (1997) deals with a character who tries to repress his own actions (of having, at least seemingly, killed his wife in an act of frustration), and in the Žižekian reading of the film, Fred Madison escapes into a fantasy space, envisioning himself as a young and virile man in a noir-like dream world. “I like to remember things my own way,” as he says (Žižek 2000).

This interpretation is fairly traditional, yet it is interesting to note that animalistic motifs and sounds are also used in this case to support that interpretation. In the first part, where we follow Fred (Bill Pullman), we hear a dog barking off screen in a few scenes. Fred notices the dog, annoyed by it in the same way that Pete (Balthazar Getty) later reacts to the experimental jazz track (heard on the radio) that we have seen Fred play at the Luna Lounge in the beginning of the film. Pete reacts to Fred’s music, as it seemingly gives him a headache, but perhaps more acutely because it reminds him of the reality which he is trying to escape from, and in the same way Fred, in the beginning of the film, reacts to the barking dog, as if it reminded him of his own primal nature: “Who the hell owns that dog?”

During the middle section of the film, then, we see a gradual disintegration of Fred’s fantasy space, and as Pete thinks of Alice and sees her face, the image becomes blurry and we cut to a spider (a black widow) crawling on the wall. Through out-of-focus shots and point of view-editing, we see the gradual disintegration of the fantasy space, and through montage editing Alice (Patricia Arquette) is compared to a deadly spider, reminding Fred of the reality he is trying to escape from (that he killed his wife out of jealousy and a feeling of inadequacy or loss of control).

In that sense, the small images and sounds of animals function as keys to unlocking Lost Highway – or at least as visual and sonic cues that can support our analysis.

The same, then, could be said of the famous traffic sequence from Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me (1992) where the image and sound of the barking dog not only emphasize the chaos and cacophony of the situation, but where the barking dog also serves to illustrate Laura’s and Leland’s attempts at repressing the abuse. In that scene from Fire Walk with Me, Leland (Ray Wise) and Laura (Sheryl Lee) are driving in a car, held back at a traffic light by a lumber truck and an old walker who is slowly trying to cross the street. On the soundtrack, we hear different non-diegetic sounds and some diegetic noises of cars speeding up and a dog barking. As Mike/The One-Armed Man (Al Strobel) pulls up next to Leland and Laura, the sound becomes louder, and we can barely make out his words, as he finally yells “It’s him. It’s your father.” Those words could naturally illustrate the reality that Laura is trying her repress (the dogs in the Palmer family’s basement, as it were), and the sound and image of the dog might by a Nietzschean motif or a more vague reference to the animalistic nature of the abuse, apart from contributing to the general chaos of the scene. As the sound editor Douglas Murray puts it:

[Laura] is putting her hands over her ears, so it’s kind of mirroring what she is going through, and that’s why Leland is honking the horn. That whole sequence is so great… We recorded all of those car revs – and they are some violent revs – and it’s just such a great cacophony. Leland realizes what is happening, and he is just looking insane, and Laura is going through such a horrific time in her life, which we wanted to illustrate. (Halskov 2015b)

Animalistic Sounds, Split Personalities and Externalization of Evil

The famous scene from Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me naturally resonates with a sequence from the original series that preceded the 1992-film. In that sequence, which is recognizable or even iconic to all Twin Peaks fans, we cut from The Bang Bang Bar to The Palmer residence where we hear the repetitive sound of a skipping record, before we witness the brutal killing of Laura’s cousin Maddy (Sheryl Lee).

What makes that scene particularly gruesome and effective is the Epsteinian use of slow-motion sound, the constant switch between real-time and slow-motion and the flickering between Leland and BOB (Frank Silva).

In the 1920s, the French filmmaker and theoretician Jean Epstein wrote and talked about the importance of photogénie, and this principle, said Epstein, could only be created by giving us close-ups of actors and by using different techniques to illustrate the inner life of a given character. One way of achieving this was grossissement (magnification) where small things are enhanced optically or where subjective sounds are magnified, for example by using slow-motion (Epstein 1921). Slow-motion could function as a sonic close-up, thought Epstein, with an added expressive quality.

While Lynch might never have seen a film by Jean Epstein, let alone heard of his theories, he has often used an Epsteinian kind of slow-motion sound, and the use of slow-motion in Maddy’s death scene has a uniquely animalistic quality, as if to illustrate the constant battle between man and primal force within Leland Palmer. “Picture and sound were slowed whenever we saw BOB struggling with Maddy,” recalls sound editor Patrick McCormick, “and the slowed audio definitely suggested the animalistic nature of BOB. This was a stylistic choice made by David Lynch, as was the repetitive needle bump sound from the record player” (author interview, December 11, 2014).

Bugs and Bad Neighbors: Blue Velvet

Something similar is at play in the film Blue Velvet which is centered on Jeffrey Beaumont (Kyle MacLachlan) and his journey into the dark underbelly of small-town America or, perhaps more plausibly, into the darkest corners of his own mind.

The film is structured as a Wizard of Oz-like fairytale in three acts, where the first and last part of the movie are shot in bright, overly saturated colors, using slow-motion and some recurring musical themes. The middle section of the movie where Jeffrey meets a troubled and alluring nightclub singer, who is aptly called Dorothy (Isabella Rossellini), is often interpreted as a dream, inasmuch as the camera zooms into a severed ear in the opening of the film and out from Jeffrey’s ear at the end of the movie (as he is lying in a chair in his garden). Was the middle section of the movie, with its noir-like characters and low-key lighting, nothing more than a reflection of the psychosexual fantasies and dreams of a young man? This question, of course, is never answered directly in the movie, but Jeffrey comes to learn that, at least in his mind, he is not as different from the dangerous gangster Frank Booth (Dennis Hopper) as he would like (us) to believe. “You’re like me,” Frank says at one point, and that line is perhaps more poignant than we would immediately think. Jeffrey might well be trying to help Dorothy, as he claims, but he spies on her out of (sexual) curiosity, and when she asks him to hurt her, he finally complies, hitting her resoundingly in the face. As Jeffrey hits Dorothy, the scene changes from real-time to slow-motion, emphasizing the primal nature of his actions, and Alan Splet’s sound design adds an animalistic quality, combining unintelligible shrieks with heavy roars of what sounds like a lion.

That scene looks and sounds like Maddy’s death scene from Twin Peaks, and, once again, it illustrates the animalistic nature of our seemingly innocent character.

The connection between Jeffrey and animals is unavoidable. At the beginning of the movie, before we are introduced to Jeffrey and the severed ear, we zoom into the lawn and see beetles in the grass, underscored by a heavy rumble on the soundtrack (what we hear is, in fact, the sound of termites eating wood, recorded by a contact microphone). Later, as Jeffrey tries to find a plausible excuse for entering Dorothy’s apartment, he calls himself “the bug man,” in what is a wonderfully polysemic reference to both the beetles (bugs), a flaw in the system (a bug), a mechanism used in surveillance and eavesdropping (a bug) and Jeffrey’s creepy, animalistic side (he is, indeed, a bug) (cf. Kaleta 1995 and Halskov 2012).

.There are many other instances like these in the films of David Lynch, and one could naturally mention the scenes with Grace Zabriskie and Harry Dean Stanton in Wild at Heart (1990), either watching wild animals in the TV or, themselves, sounding like ferocious animals. It would also be natural to mention the strange character O.O. Spool (Jack Nance) who talks to Lula (Laura Dern) and Sailor (Nicolas Cage) about his dog before he suddenly starts to bark.

Examples like that abound in the films of David Lynch, and this essay has hardly been able to explore all the relevant scenes and sequences, nor has it explored all the potential meanings and functions of the animalistic motifs and sounds in Lynch’s works. Hopefully, however, this essay could help shed a light on one of the most significant yet often overlooked aspects of David Lynch’s productions. In other words, we might think that Fred Madison is posing an arbitrary question when asking his wife, “Who the hell owns that dog?” Then again, he might be posing a very relevant question, and the answer might hold a key to unlocking yet another part of the Lynchian mystery.

Literature

Epstein, Jean (1921), “Grossissement,” Bonjour Cinema. Paris: Editions de la Sirère, pp. 93-108.

Halskov, Andreas (2012), “Blue Velvet og det nysgerrige øre,” 16:9, #46, June. Online: http://www.16-9.dk/2012-06/side07_anatomi.htm.

Halskov, Andreas (2015a), “Interview: Gary Hershberger & Dana Ashbrook,” Det røde rum. Online: https://detroederum.wordpress.com/boger/tv-peaks/gary-hershberger-dana-ashbrook/.

Halskov, Andreas (2015b), “What’s the Frequency, David? Noise and Interference in the Films of David Lynch,” 16:9, August 16. Online: http://www.16-9.dk/2015/08/whats-the-frequency-david/. The video-essay was later brought in Filmmaker Magazine.

Kaleta, Kenneth C. (1995), David Lynch. New York: Twayne Publishers.

Nietzsche, Friederich (2007 [1872]), On the Genealogy of Morality and Other Writings, edited by Keith Ansell-Pearson, translated by Carol Diethe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Žižek, Slavoj (2000): The Art of the Ridiculous Sublime: On David Lynch’s “Lost Highway”.

Washington: University of Washington Press.