With the upcoming release of Sofia Coppola’s latest feature Priscilla, an adaptation of Priscilla Presley’s memoir chronicling her relationship with Elvis Presley, it’s the perfect time to analyze the profound impact Coppola’s filmography has had on independent film culture. From Lost in Translation to Marie Antoinette and Somewhere, Coppola has established a definitive name for herself through the bold, empowering female-centered narratives and recognizable dreamy nostalgia alive in most of her films. Her distinctive style put her ahead of her other filmmaking peers when, at age 29, she first broke out onto the indie film scene in 1999 with her feature film debut The Virgin Suicides.

Approaching the expansive topic of female adolescence and womanhood in all its complexity and odd beauty is a forever relevant subject that contemporary filmmakers such as Diablo Cody, Greta Gerwig, and Marielle Heller have tackled. However, no female coming-of-age movie about teenage girls on the precipice of burgeoning maturation and self-discovery amidst parental restraint has struck as deep a chord as The Virgin Suicides.

An adaptation of Jeffrey Eugenides’ 1993 novel set against the backdrop of an idyllic neighborhood of a Detroit suburb, The Virgin Suicides follows the tragic demise of the Lisbon sisters: Lux (Kirsten Dunst), Mary (A.J. Cook), Therese (Leslie Hayman), Bonnie (Chelse Swain), and Cecilia (Hanna Hall), through the lens of four infatuated boys who live on the same street.

The film opens with shots of an ordinary day in the neighborhood—the sun is shining, the birds are chirping, and a neighbor is mowing his lawn. Suddenly, the camera cuts to the Lisbon family’s youngest, Cecilia, lying lifeless in a bloody bathtub after her first suicide attempt. It’s a drastic and jarring juxtaposition that immediately places the viewer in the mindset that there’s darkness brimming beneath the surface of this almost-Stepford wife community. It’s far from suburban paradise.

After being taken to the hospital, Cecilia has an encounter with a doctor—a revealing conversation that illustrates how misunderstood she is.

“You’re not even old enough to know how bad life gets.”

“Obviously, doctor, you’ve never been a thirteen-year-old girl.”

In an effort to get Cecilia to socialize more with boys her own age, the Lisbons throw an exclusive party for the sheltered girls. Cecilia, however, removes herself fairly early on during a scene where her sisters and the boys from across the street are giggling and laughing at a boy with Down syndrome, Joe, treating him as a spectacle. This is a prime example of teenagers trying to conform and go along with what their peers are doing. Outsider Cecilia didn’t want to be part of the joke, looking uncomfortable and sad.

Cecilia doesn’t have much dialogue in the movie: her second gruesome suicide attempt follows not long after her first, in which she succeeds by leaping from the home’s second story and impaling herself on the fence’s spikes in the front yard. In a powerful wide shot, the Lisbon patriarch (James Woods) is holding Cecilia in his arms, and the mother (Kathleen Turner) shields her daughters away from the traumatic sight.

That one line Cecilia speaks in the hospital is the most revealing and sets the inevitably dismal tone moving forward. Cecilia’s suicide becomes the talk of the town, everybody gossips and assumes why she took her life. Naturally, certain neighbors blame the dysfunctional parents—an uber-religious and over-protective mother, and an endearing, albeit clueless father who does his best. The delicate topic circulates throughout the school and is prevalent in the sensationalized media coverage. Coppola—who grew up in a predominantly male environment—tastefully handles such delicate and intense subject matter with innate respect and understanding. Her feminine instincts were instilled within her from a young age.

Aiding in the further downward spiral of not only the Lisbon sisters are the other sociopolitical and economic factors at play in mid-1970s Michigan that Coppola interweaves within the narrative. Not only was there a drastic decline in the automobile industry but cemetery workers were on strike. The ‘70s were a prescient, crucial era for labor union movements across the United States, one of them taking place on March 24, 1970, at a Detroit cemetery where about 50 workers at three Roman Catholic cemeteries walked off the job after six months of unsuccessful labor contract negotiations.

In that same year, on September 15, over 400,000 auto workers at Detroit-based General Motors (GM) walked out—a strike that endured for more than 67 days. The revolutionary strike ruined the nation’s economy as strikers fought for better working conditions, better pay, and inflation protection. Thus, the disarray occurring in the Lisbon family is also reflected in the outer world.

The four male friends (Chase, Parkie, Tim, and Paul) mentioned earlier (an older version of one of the boys narrating the film, voiced by Giovanni Ribisi) are riveted, intrigued, and beyond fascinated with the Lisbon sisters. It’s important to call attention to the notion that the girls are all observed, dissected, and lusted over through a male gaze. There is no female first-person perspective here, which is ironic given that the movie is directed and written by a woman. Thus, making the conscious decision not to tell the story from the Lisbon sisters’ points of view symbolizes they are merely sexualized objects for male desire and objectification.

Laura Mulvey’s Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema denotes the term “male gaze” (first used by art critic John Berger) as one in which the portrayals and narratives of females in cinema are purely constructed in a limited scope, whose sole purpose is to be objectified and to satisfy the psychological desires of men and—on a broader level—male society as a whole. The Virgin Suicides utilizes this one-sided viewpoint through the eyes of teenage boys to further symbolize the isolation and alienation of the Lisbon girls as if they are voiceless and passive bystanders in their own lives. They are seemingly at a distance, out of reach, and intangible facets of the boys’ active imaginations—mysteries the boys are eager to solve and understand.

After Cecilia’s “accidental” death, the boys get a hold of her diary—one of the many trinkets and other objects from the girls they collected over time. Tim Weiner (known as ‘The Brain,’ played by Jonathan Tucker) tries to decode Cecilia’s handwriting. He mentions that her Is are all over the place, signaling “emotional instability.”

“What we have here is a dreamer. Someone completely out of touch with reality – when she jumped, she probably thought she would fly.”

Weiner’s self-assured comment about what he perceived as Cecilia’s state of mind is yet another example of the obsession to dissect the female, to get to the source of her pain. In some way, it could be gleaned that the boys saw themselves as saviors—only they could save the girls from themselves. These inferences about Cecilia’s inner world help them gain closeness to her and the others, even though they could never truly grasp or know what she was experiencing every day of her short life. The collected objects serve as a portal into the Lisbon girls’ psyches and their deepest thoughts, allowing them to feel a transcendent sensation of connection.

“We felt the imprisonment of being a girl.”

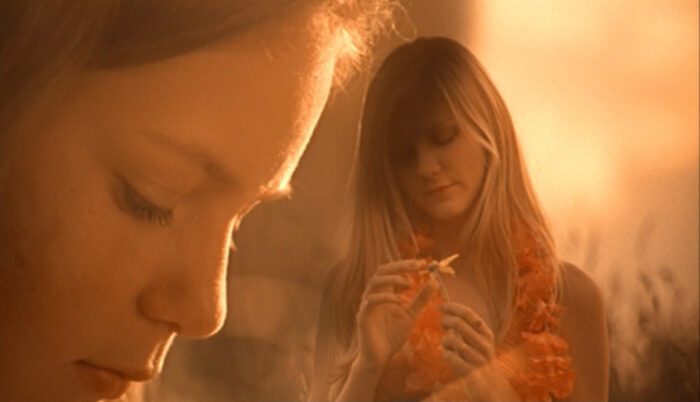

Perhaps, these collections of memories and mundane insights into their daily existence aid in providing meaning in the boys’ own lives, calling back to the concept of females as a mere catalyst for male desire and inner introspection. Beautiful montages of the girls in a sprawling field flicker across the screen, giving off a dream-like quality that is synonymous with Coppola’s signature cinematic style.

The precocious 15-year-old Lux (embodied by Coppola’s muse Kirsten Dunst) is at the forefront of the film’s male gaze ideology. She is far from the stereotypical girl-next-door; she’s an enigma that nobody can seem to crack—not even the tantalizing Trip Fontaine (Josh Hartnett) which drives him crazy.

After Mrs. Lisbon agrees (on a few conditions, of course) to let the girls go to the homecoming dance, their lives begin to look brighter and more optimistic. Lux and Trip win homecoming king and queen and, with iconic ‘70s hits such as Styx’s haunting “Come Sail Away” blaring in the background, it’s a realistic snapshot of a teen dance. It’s also truly the first moment in the entire film that they look happy. Unfortunately, that spark of hope and happiness doesn’t last long enough, a further symbol of how fleeting life is and how adolescent emotions come as quickly as they go.

Lux and Trip spend the night together on the football field. When Lux wakes up the next morning, Trip is out of sight. That was the last time they would ever see each other again. Lux’s breaking of curfew results in drastic measures being taken: the girls are pulled out of school and are forbidden to leave the house. The impeccable implementation of lighting throughout the movie underscores the tonal shifts and puts the viewer into the exact mood conveyed in every scene. In an emotional scene where Lux’s mother forces her to burn her favorite rock records, it’s perceived that the music is what influences Lux’s sexual nature and rebelliousness. The atmosphere in the house is gloomy, dull, and far from warm, a precise mirroring of the depressed inhabitants who live there.

In a defiant act to save their last tie to Cecilia, the girls band around her favorite elm tree that is infected with a fungus and would be chopped down. Eventually, the other elm trees face the same fate, too. An important element of the narrative Coppola emphasizes is that of impermanence. As time accordingly marches on, the Lisbon house is filmed in a time-lapse segment marking its decay and lack of care over the weeks and months of neglect. Travel catalogs become the only way the girls escape their dreadful prison, and the boys go with them.

“Unable to go anywhere, the girls traveled in their imaginations.”

These “impossible excursions” that would never come to fruition stayed with the boys for the rest of their lives, as dreams become better than wives—dreaming and yearning for something other than real life is another theme in the film. The girls began to fade from their memories, turning into pale shadows of who they could have been. They hatch a plan to escape with the Lisbon girls, but their dreams of going on the open road never come to be. The suicides of the rest of the Lisbon girls followed, with Lux being the last to go, a contagious symptom of the poison that filled the air after Cecilia took her life. The town speculated what happened to Lux, Mary, Therese, and Bonnie, but they didn’t care—it’s only a superficial facade. They go back to their swanky parties and daily tennis games, indicating how quickly (and rather disturbingly) people move on from horrific tragedies. The Lisbon girls wanted to be remembered.

After revisiting Sofia Coppola’s The Virgin Suicides, the exact feelings, emotions, and thoughts I had upon the first watch are instilled within me. Coppola created a sensitively poignant masterpiece that is about much, much more than repressed teenage girls in an upper-middle-class suburban town. It’s about life and the loss of it. It’s about falling in love, falling out of love, getting one’s heart broken and never recovering. Coppola manages to infuse many timeless aspects of adolescence that are mesmerizing, poetic, stark, and unsettling. The harrowing demise of the Lisbon girls is an allegory for a society and upbringing that failed them. At its prolific core, Coppola’s film is about how memories slip away and come back, and how human connection in unpredictable times should be savored because life’s cruel uncertainty waits in the wings.