The Boondock Saints is an amazing example of a cult classic. It isn’t the film alone but the surrounding stories that make it unique. That’s because The Boondock Saints isn’t merely about Irish vigilantes slaughtering mobsters, it’s about a first-time filmmaker’s meteoric rise alongside the cautionary tale of his rocket descent. Even those who don’t care for the movie should appreciate the varied implications of this indie actioner’s existence.

Twenty-five years ago, The Boondock Saints got released in five U.S. theaters. It didn’t do well, but instead of fading into oblivion, it lingered in obscurity. As the movie spread throughout video rental shops, Blockbuster in particular, the audience grew. Devoted fans evangelized the flick to anyone listening. Meanwhile, watching the film with such disciples meant more than a mere viewing. Either throughout the picture or afterward, one got treated to the mythology of the movie’s origin, the Gospel of Troy Duffy.

It’s the tale of a blue-collar bartender who left Boston for L.A. One night, he observed a drug dealer swiping the last cash from a dead junkie. The incident inspired him to write a script about vigilante justice. That screenplay would attract the attention of Miramax, secure a fifteen-million-dollar budget, and seat Troy Duffy in the director’s chair.

Of course, that’s only part of the story. Mainly, the portion people prefer to hear. It sells the fabled promise of overnight success so many creatives desperately desire to be true. Furthermore, the quality of the film suggests anyone can make a movie given the opportunity.

The Boondock Saints follows the MacManus brothers. Fraternal twins living in Boston, they run afoul of Russian gangsters while celebrating St. Patrick’s Day. When the criminals are found dead, eccentric F.B.I. agent Paul Smecker enters the scene. His Sherlockian investigation of the deaths paints a portrait of self-defense, and when the brothers turn themselves in, they confirm his conclusions. However, despite being let off the hook for these justifiable killings, the twins soon believe they’re God’s chosen enactors of punishment. What ensues is a cartoonishly violent extravaganza involving Hong Kong inspired shootouts, Agent Smecker’s increasingly unhinged investigation, and the hard lesson that being action heroes can have painful, tragic consequences.

Nonlinear storytelling is the main narrative trick in The Boondock Saints. Every action sequence cuts off before bullet one, jumping to Smecker alongside Boston police. Flashbacks verify the brilliant investigator’s conclusions to the point he eventually appears in them as if an observer.

This interesting convention puts viewers more in line with the police perspective than the vigilantes’, wondering what happened. Furthermore, the cops’ behavior at each crime scene shows their evolving relationship with Smecker. What starts out as Boston P.D. being resentful, dismissive, and homophobic about the flamboyant investigator gradually shifts into obvious respect as they dutifully note his every observation.

Action blends into the ongoing narrative without changing gears too much. Basically, police provide exposition interspersed by wild gunfire. This also allows The Boondock Saints to highlight its own absurdity.

Although films like Die Hard (1988) and Lethal Weapon (1987) featured flawed heroes who didn’t shake off injury like invincible demigods, most high-octane violent adventures didn’t pursue humanity and plausibility. Instead, they embraced bombastic events that bordered on the comically absurd, showcasing the surreal nature of action films. Movies like Speed (1994), Bad Boys (1995), and The Rock (1996). Then there’s The Last Action Hero (1993) which failed in its attempt at a postmodern deconstruction of the genre (at least as far as the box office). Yet, the movie utilized a hallmark of 90s cinema: self-awareness.

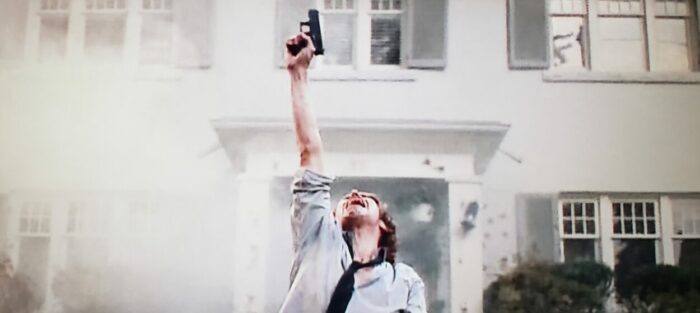

In its own clumsy way, The Boondock Saints borrows from all these action influences. The MacManus brothers aren’t bulletproof, though they are borderline superheroes. For example, one jumps off the top of a building and only gets a temporary limp after landing on concrete. The vigilantes seem like strategic idiot savants until drunkenly shooting a cat by accident. They also possess plot dependent accuracy; dead eye marksmen when spinning upside down yet unable to shoot a nearby hitman whose death would interfere with an intended plot twist. Meanwhile, the brothers bicker like an odd-couple buddy-cop comedy.

They’re human beings with definite flaws who pull off superhuman feats of action through dumb luck. Still, the movie makes it a point to observe their successes aren’t a matter of skill.

Agent Smecker remarks at one point, “Television is the explanation for this—you see this in bad television. Little assault guys creeping through the vents, coming in through the ceiling—that James Bond shit never happens in real life! Professionals don’t do that!”

As such, the film tries to have its cake and eat it too. In the essay “Dark Humor in Cat’s Cradle” Blake Hobby referred to metafiction as “this self-referential quality, where fiction calls attention to its own status as art.” Applying that to The Boondock Saints, the movie preempts criticism of its own absurdity by highlighting the ridiculous origins of the MacManus brother’s strategies, essentially calling out the ludicrous nature of all action movies. Openly stating that the film’s violence is unrealistic then plays into the narrative.

When the vigilantes finally meet defeat, it nearly shatters the group. Calm and cool when winning, getting shot up instantly turns them into screaming, frightened children. Apparently being on a mission from God doesn’t come with Christ’s own Kevlar vest. This oddly raises the stakes mid-movie as the titular saints realize they can die in this endeavor. After all, these aren’t vengeful fellows with little or nothing to lose à la Death Wish (1974), Out for Justice (1991), Hard Target (1993), or The Substitute (1996). The twins have a moral motivation for this kind of street justice. Their sidekick, however, is a man pushed too far.

![[L to R] David Ferry, Brian Mahoney, Willem Dafoe, and Bob Marley as Dolly, Duffy, Smecker, and Greenly in The Boondock Saints (1999). Screen capture off of DVD. Franchise Pictures. Three detectives and FBI Agent Smecker ride a cargo elevator while discussing a crime scene.](https://filmobsessive.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/20240305_051639-700x342.jpg)

Though it doesn’t strain credulity too much, The Boondock Saints is rife with such coincidences. The MacManus brothers always have the skills, knowledge, or chance encounters necessary to advance their plans. Even Agent Smecker can leap to conclusions the clues don’t always indicate. While this keeps the plot constantly moving forward, it strains reason, although no more so than Steven Seagal charming people in any movie.

Perhaps a better cast would help sell some of the flaws. But the acting in The Boondock Saints isn’t exactly top tier. Sean Patrick Flannery and Norman Reedus are great as the leads Connor and Murphy MacManus, yet they have cringeworthy Irish accents dueling for worst with Tom Cruise in Far and Away (1992) and Julia Robberts in Michael Collins (1996). That is when they remember to use it. Similarly, mob boss Giuseppe “Papa Joe” Yakavetta played by Carlo Rota is performed with an accent that can only be described as foreign. About the only person off the top shelf is Willem Dafoe as Agent Smecker. He can be hypnotically histrionic especially when the strain of the case pushes him over the edge.

Hit-or-miss acting aside, the movie is also a hodgepodge of various cinematic technics popularized in the 1990s. Slow motion gunfights abound as does a camera orbiting people during exposition. Much of The Boondock Saints, however, is Filmmaking 101 which can give it an amateurish quality. Transitions involve fading to black so often it could be a drinking game cue.

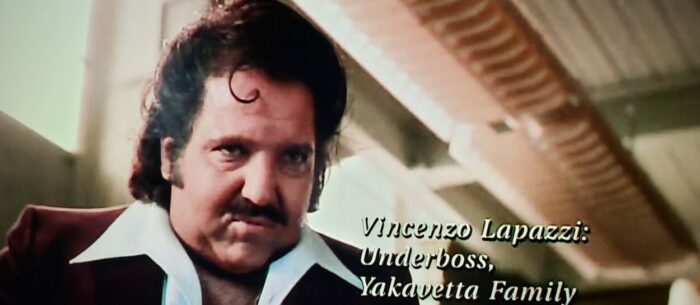

What I’m getting at is that the overall movie seems to lack intention. When quality acting occurs, it elevates pedestrian dialogue. And the script doesn’t have much conversation, preferring to reveal character details simply by stamping statements on screen—this is mob boss Generic Italian name, rank, serial number, etc. The pastiche of cinematic techniques never seems like a choice, or homage, rather slickness stolen from other flicks.

In a way, those borrowed techniques made the film familiar without feeling pretentious. Plus, many directors have done similarly. Almost every J. J. Abrams movie uses that orbiting camera trick during ponderous exposition dumps to make them seem more energetic. And Tarantino has long been given a pass on epic cinematic theft under the banner of homage.

The difference in my opinion is partly a matter of the era during which The Boondock Saints emerged alongside later facts about Troy Duffy. The 1990s saw a boom in independent film production. As detailed in Peter Biskind’s Down and Dirty Pictures: Miramax, Sundance, and the Rise of Independent Films, a kind of cinematic gold rush occurred. Anything that fit into a certain mold got snapped up by aspiring studios. This resulted in a deluge of films similar in content and stylization.

My Private Idaho (1991) tells a tale of male prostitutes with a Shakespearean bent then along comes Johns (1996) leaning into gritty realism with a shade of sentimentality. Quentin Tarantino makes hitmen amusing rogues who chitchat about mundane trivialities during crimes gone wrong; enter Love and a .45 (1994), Killing Zoe (1994), and Truth or Consequences, N.M. (1997).

Talking about his documentary Overnight (2003), Mark Brian Smith mentioned, “One critic said our movie was one of the best representations of the go-go ’90s… producing and releasing was secondary to acquiring, and that’s why films got shelved and certain filmmakers got forgotten about.”

Overnight chronicles the rise and fall of Troy Duffy. What started as a making of documentary soon turned into a tale of alcohol fueled arrogance and hubristic downfall. It shows Duffy being handed the keys to Hollywood then effortlessly alienating every golden opportunity with an abrasive personality that is oafishly devoid of humility. Pissing it all away reduced the budget of The Boondock Saints significantly and removed any possibility of marketable talent like Keanu Reeves, Patrick Swayze, or Kenneth Branagh. The documentary is essentially witnessing an act of arrogant self-immolation that can make it hard to enjoy the movie he finally produced. Duffy comes across so unlikable it’s hard to want him to succeed. And I think that’s bled into contemporary criticism, a sign of which is any mention of his personality. It certainly soured my enjoyment of the movie.

Plus, in the post Pulp Fiction (1993) period any movie remotely similar to Tarantino received harsh criticism for being a copycat. The Boondock Saints with its quirky characters, nonlinear narrative, and stylized violence certainly falls into the knockoff bin. Consequently, its imperfections become an unflattering caricature inadvertently critical of the style Tarantino inspired. Still, for many this movie isn’t delightfully cheesy enough to be forgiven, especially with politically incorrect moments that aren’t ironic enough to get a pass.

The Boondock Saints emerged in an era of imitators, snapped up by a Miramax milking a dying cash cow, the Tarantino breed. Writer-director Troy Duffy seemed to show overnight success was possible. Unfortunately, not every star that rises is able to hang in the heavens. It certainly doesn’t help when someone ascendant straps on a rocket pack and aims straight for the ground. Moreover, whatever made the script shine like gold to studios, Duffy couldn’t put it on screen. So, he made a movie just bad enough to seem like anyone could do the same.

Today, the movie inhabits a niche loved by some and adamantly hated by others. It didn’t age well. Yet, it was once dumb fun expressing the fact it doesn’t take genius to make something entertaining. The overnight opportunity so many seek wasted on a fool, The Boondock Saints is a Hollywood dream and nightmare rolled into one.