The following contains spoilers for Avengers: Age of Ultron, Avengers: Endgame, WandaVision, and Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness.

Full disclosure: apart from Captain America: The First Avenger (2011) and its sequel The Winter Soldier (2014), I must confess that I am not a fan of the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU). Somewhere during “Phase Two,” I contentedly dropped out and have only checked back in on rare occasions to finish out a particular story arc (Avengers: Age of Ultron [2015], Captain America: Civil War [2016]) or when the treatment of a new character looked kind of interesting (Doctor Strange [2016], Black Panther [2018]). The latter occurred most recently with the mannerist, conceptually brilliant WandaVision (2021), a nine-episode miniseries that aired on Disney+ to set up “Phase Four.” Created by head writer Jac Schaeffer and directed by Matt Shakman, it served as the first standalone story about Wanda Maximoff (Elizabeth Olsen), the telepathic, telekinetic Avenger who becomes the Scarlet Witch, the main antagonist in Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022).

Technically, Wanda was not so much a new character in 2021 as a character who had been sorely underused in Age of Ultron and Civil War (and, I’m told, the last two Avengers movies [2018, 2019]). WandaVision focuses on her married life with the android Vision (Paul Bettany) in the fictional suburb of Westview, NJ. Moving chronologically from the 1950s to the present, episode by episode, two thirds of the series is presented in the style of at least one popular sitcom from a decade in commercial television history, complete with fake advertising breaks appropriate to the period: I Love Lucy and The Dick Van Dyke Show for the 1950s (Episode 1), Bewitched for the 1960s (Episode 2), The Brady Bunch for the 1970s (Episode 3), Family Ties and Full House for the 1980s and 1990s (Episode 5), Malcolm in the Middle for the 2000s (Episode 6), and The Office and Modern Family for the 2010s (Episode 7). The irony of this self-reflexive conceit is that WandaVision was Marvel Studios’ first foray into television with the MCU’s continuous, ever-expanding storyline, and that Olsen is the younger sister of twins Mary-Kate and Ashley, former child stars who appeared on Full House. And what is a classic sitcom without a spin-off? Wanda’s nosy neighbor (wicked witch Agatha Harkness, deliciously played by Kathryn Hahn) is set to return next year in her own series, Agatha: Coven of Chaos.

Over the course of WandaVision, we gradually learn that Wanda has been traumatized by the losses she has suffered—her parents when she was a child growing up in war-torn Eastern Europe, her twin brother Pietro in Age of Ultron, and finally her beloved Vision in Avengers: Endgame (2019)—and started a new, virtual life as a way of coping with her grief. Inspired by her favorite U.S. sitcoms from her childhood, she recreates Vision and together they raise two boys in Westview, but peculiar disturbances interrupt her nostalgic fantasy. This illusion of an idealized, middle-class family provides a temporary psychological escape for Wanda through the power of denial. Meanwhile, the actual residents of Westview whom she holds hostage are barely conscious of being “cast” in her “show.” In the end, Wanda makes the difficult decision to sacrifice her family to free Westview, but her acceptance is not a redemption. The final scene of her immersed in the Darkhold (Marvel’s book of dark magic) confirms that we have been watching the origin story of a new antagonist, the Scarlet Witch, as per Wanda’s trajectory in the Marvel comics.

Star Elizabeth Olsen, who made her stunning debut in the film Martha Marcy May Marlene (2011), delivers a finely calibrated performance like nothing I ever thought I would see in a Marvel Studios production, shifting between a humorous camp sensibility in Wanda’s sitcom “roles” and sincere emotion when that meta-theatricality breaks down. Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (henceforth DSMM) is as much a continuation of WandaVision as a sequel to Doctor Strange, with Stephen Strange (Benedict Cumberbatch) protecting a new character named America Chavez (Xochitl Gomez) from the Scarlet Witch and the demons she summons. America is a teenager who possesses the ability to travel through parallel universes (the “multiverse”), and the Scarlet Witch pursues her with the intent of harnessing her power to reunite with her children in Westview, which would kill America in the process. After reprising her role, Olsen said that her characters are neither heroes nor villains, and yet some fans had trouble reconciling their empathy for Wanda and her turn to the Darkhold. For me, it is exactly this level of complexity that makes DSMM the exceptional sequel to improve on an original film (I found the first Doctor Strange all but unwatchable) and a welcome addition to the MCU.

Wanda Maximoff/Maximum Melodrama

“You break the rules and become a hero,” the Scarlet Witch tells Doctor Strange, “I do it and I become the enemy. That doesn’t seem fair.” The Wanda story arc supports her provocative contention, demonstrating that within this masculinist sci/fi-action franchise, there lied an untapped potential for what film critics have called “woman’s film” melodrama. Feminist film theorist Linda Williams has explained that “woman’s film” melodrama is a genre comprised of “films addressed to women in their traditional status under patriarchy—as wives, mothers, abandoned lovers, or in their traditional status as bodily hysteria or excess, as in the frequent case of women ‘afflicted’ with a deadly or debilitating disease.” Williams observes that the distinguishing feature of the genre is “the sensation of overwhelming pathos” for the female protagonists, achieved not only through the “portrayal of weeping” in the films themselves, but also in how the “audience sensation mimics what is seen on the screen.” No wonder that in the genre’s heyday of the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s, it was colloquially referred to as the “weepie.” Among the most celebrated examples include Stella Dallas (1937), Dark Victory (1939), Rebecca (1940), Mildred Pierce (1945), Letter from an Unknown Woman (1948), All That Heaven Allows (1955), and Imitation of Life (1959).

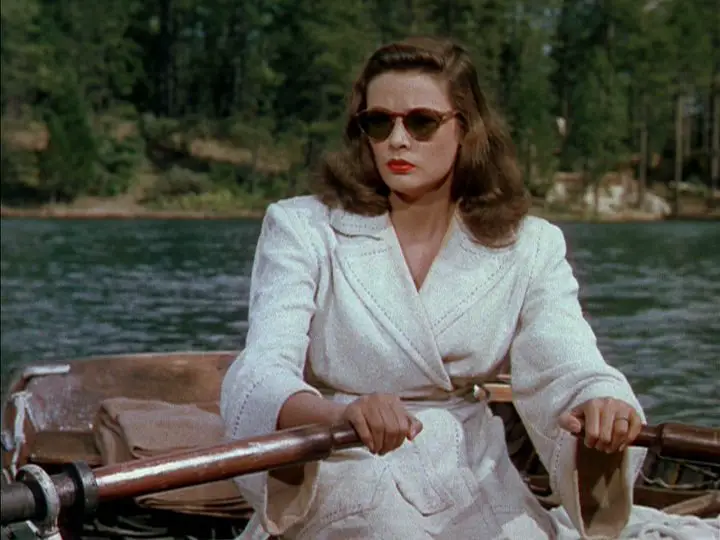

Wanda reminds me of my favorite female character in “woman’s film” melodrama: Ellen Berent (Gene Tierney) in Leave Her to Heaven (1945), a Technicolor fever dream directed by John M. Stahl and adapted from the 1944 novel of the same name by Ben Ames Williams. Tierney was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Actress, but lost to Joan Crawford in Mildred Pierce (talk about melodrama!), and the film became Twentieth Century-Fox’s highest grosser by 1946. Both Wanda and Ellen are deeply passionate women who destroy themselves in following their single-minded obsessions. Driven by rage, Wanda sets out to reconstruct her family, while the jealous Ellen seeks her husband’s love and attention. The major difference is that Ellen’s madness is hinted at early in the film. Having lost her father, whom she adored, the newlywed woman forms a possessive attachment to her husband Richard (Cornel Wilde), afraid of losing him next. With its pop Freudian psychology, the film overtly attributes Ellen’s neurosis to an Electra complex—she insists that Richard resembles her father. Ellen’s fears of abandonment are not unjustified, however, as Richard allows family members to intrude on their honeymoon, beginning with his younger brother Danny and going so far as to invite Ellen’s mother and cousin Ruth to stay with them.

Just as the Scarlet Witch attacks the Kamar-Taj, possesses her “other self” in Westview, and violently dispatches the members of the Illuminati, Ellen is also capable of great cruelty and almost witch-like manipulation (Richard may be more right than he realizes when he jokes, “You know, if you lived in Salem a hundred years ago, they would have burned you”). Seeing Danny as a competitor for Richard’s attention, she lets him drown while pretending to teach him how to swim. After learning that Richard and Ruth have fallen in love, she commits suicide and frames Ruth for her murder.

Yet, if Leave Her to Heaven does not endorse all of Ellen’s actions or even ask its audience to find her conventionally sympathetic, it also contextualizes her behavior in a way that renders easy judgements (she’s a “bad woman,” she’s “just crazy”) completely wrongheaded. Partly through Tierney’s sensitive performance, the film reveals the grievous social conditions under which this “badness” is acted out, not the least of which is the lack of understanding and support for women’s mental health in the mid-1940s. Richard does seem to prioritize the feelings of others over those of Ellen, oblivious to her needs and desires as his wife, apparently preferring the homosocial company of his brother and avuncular groundskeeper. For example, when Ellen throws herself down the stairs to cause a miscarriage, it is not the act of a femme fatale, but a woman who has been made a “prisoner,” to use Ellen’s word choice, in a domestic environment, as plans for her family’s future—to say nothing of her own—are made for her.

Whether Ellen or Wanda are villains is beside the point. The spaces that Leave Her to Heaven and DSMM give them for expressing such excesses of emotion makes them the most compelling characters in their respective films. As Olsen told Hollywood Life in an interview, “My goal is to always have [Wanda] have some sort of evolution, and the evolution in this for me was really empowering.” Elaborating, Olsen continued, “She has a new kind of confidence that we haven’t seen in 8 years, and she’s really not apologizing for anything. She feels very clear in her beliefs. I find it very admirable, and I enjoyed throwing her into this journey of madness. I think it’s okay to play characters that people get frustrated with sometimes. I enjoy that as an actor.” Like Ellen, the Scarlet Witch is perversely fun to watch. Aided by the typically offbeat horror-movie touches of director Sam Raimi, Olsen makes her character scary without reducing her to a one-dimensional monster-of-the week. Mrs. Berent’s identification of Ellen’s problem—“that she loves too much”—might also be said of the Scarlet Witch, and therefore it’s hard not to be moved when she relinquishes her children to her “other self,” who assures her, “they’ll be loved.”

While it appears that the Scarlet Witch kills herself when eliminating the Darkhold at the end of DSMM, how she will factor into future films or TV series set in the MCU remains uncertain. Although Olsen told The New York Times that she would be open to returning to the MCU for a Scarlet Witch film, she added, “But it really needs to be a good story. I think these films are best when it’s not about creating content, but about having a very strong point of view—not because you need to have a three-picture plan.” Regardless of where her story goes from here, we can be sure of one thing: it’s Wanda Maximoff’s multiverse and we’re just living in it.

Will Scheibel’s new book Gene Tierney: Star of Hollywood’s Home Front, on the star of Leave Her to Heaven, is available this month from Wayne State University Press.