In the U.S. Labor Day weekend is upon us: observed the first Monday in September, Labor Day celebrates the contributions of workers to their economies and societies, just as much of the rest of the world does on International Workers’ Day on May 1. Regardless of whether you celebrate in May or September, our staff at 25YL/Film Obsessive has a list of Labor Day film recommendations for your weekend viewing. From comedy to tragedy, documentary to fiction, classic to cult, there’s a little of something here for everyone. Celebrate with us those who toil in mines, offices, and factories—and those daring enough to just say no to the indignities their work forces upon them.

Modern Times (1936)

Then the most famous star of cinema and possibly the most recognizable face in the entire world, Charlie Chaplin resisted the oncoming and quickly ubiquitous direct-sound technologies sweeping his industry for the better part of a decade. By 1936 there were no films other than “talkies.” But his long-awaited Modern Times was at its heart still a silent film, the kind that wowed crowds and endeared his Tramp character to millions. The difference: direct sound, including human voices, in a few key moments, including the Panopticon-like surveillance system his employers used to monitor his character’s activity and an inspired bit of gibberish lyrics in a deliriously giddy song-and-dance finale.

But Chaplin’s was more than an attempt to hold on to the past: it was a warning about the future, not to embrace new technologies too quickly or carelessly. In Modern Times, the forces of industrial invention conspire to surveil, to monitor, to ensnare and enslave the worker in the cogs of a giant machine whose only purpose is to benefit its already-rich-and-getting-richer ownership. A rich man himself, Chaplin sided with the worker: he claimed his work had no political significance, but it was hard to mistake the image of the Tramp, even accidentally, holding up a flag and leading a parade of protesting workers. His were Modern Times, indeed. — J Paul Johnson

The Grapes of Wrath (1940)

Though times today may not be as dismal as the Great Depression, a film like The Grapes of Wrath still resonates significantly. While its story is from decades past, its themes hold a relevant truth even now. Yet, the importance of the movie isn’t just its depiction of struggle but the staunch perseverance of protagonists who keep on going despite degradation.

Based on the Pulitzer prize-winning novel by John Steinbeck, this 1940s classic tells the tale of the Joad family. Forced off their family farm by landowners, they cross the United States enduring one hardship after another in search of a brighter future. Ending more happily than the novel, director John Ford serves a stirring story of endurance.

The film features several iconic scenes, not least of which is the “I’ll Be There” speech delivered by Henry Fonda. Portraying Tom Joad, a haunted look on his face, Fonda tells troubled Ma Joad where to find him in the future. It’s a rare kind of monologue, precise and deep, touching on all the ills and wonders of the world without overstaying its welcome. Hearing the speech, it’s no wonder there are those to this day searching for the ghost of Tom Joad. — Jay Rohr

They Live by Night (1948)

Before becoming a director in Hollywood, Nicholas Ray worked in U.S. federal agencies of President Roosevelt’s New Deal, during which time he traveled through the South and Midwest. This time on the road as head of the Theatre Section of the Special Skills Division in the Dept. of Agriculture’s Resettlement Administration (RA) made him an ideal choice for RKO Radio Pictures producer John Houseman to direct They Live by Night, a low-budget, workmanlike adaptation of Edward Anderson’s Depression-era novel Thieves Like Us. It would be Ray’s first film and an early example of the outlaw-couple tradition in film noir.

Although it was shot in outside of Hollywood in Southern California rather than on location in rural Texas, the setting for the novel, Ray did not rely on exteriors created in an RKO soundstage. George E. Diskant’s haunting cinematography even resembles photographs taken for the Farm Security Administration, which absorbed the RA in 1937. The film’s social realism and progressive politics—Ray had been a member of the American Communist Party—qualified it for a place on critic Thom Anderson’s list of “film gris.” Noir or gris, it represents Ray’s best work and remains one of the great laborist crime dramas of the Classical Hollywood era. — Will Scheibel

The Wages of Fear (La Saliare de la Peur, 1953)

The Wages of Fear (La Saliare de la Peur) may just be the most exciting, pulse-pounding thriller in cinematic history. Its plot is bare-bones: four down-on-their-luck European vagabonds are hired at $2000 each to drive two trucks loaded with explosive nitroglycerine over 300 miles of treacherous mountain dirt roads with the intent of using the chemicals to extinguish a company fire. Thirty minutes separate their two trucks, each with two men. Why? to limit fatalities in case either truck explodes.

Director Henri-Georges Clouzot makes the most of the film’s second half, which is nearly without peer in its suspense. The drivers must back onto rotting planks over a mountainous ledge, navigate pools of highly flammable oil, and use their cargo to detonate obstacles. Georges Auric’s score and Armand Thirard’s cinematography create an almost unbearable tension: watch and you feel as if your sofa might burst into flames at a single, slight wrong movement.

So tense is The Wages of Fear you might overlook its anti-corporate message: that the American company whose oil field is aflame is already well known for its unethical practices and exploitation of local labor, that the job assigned to the four drivers is considered way too dangerous for their own more-valuable unionized employees. Corporations are all too quick to exploit non-unionized workers, especially in underdeveloped nations (the film is set in an unspecified Latin American country), all to eager to let the poor gamble their health, their lives, to preserve the company’s profit. But Clouzot doesn’t exactly idolize the type of men willing to take these assignments, either, making The Wages of Fear a more ideologically complex film than most simple anti-capitalist fare. — J Paul Johnson

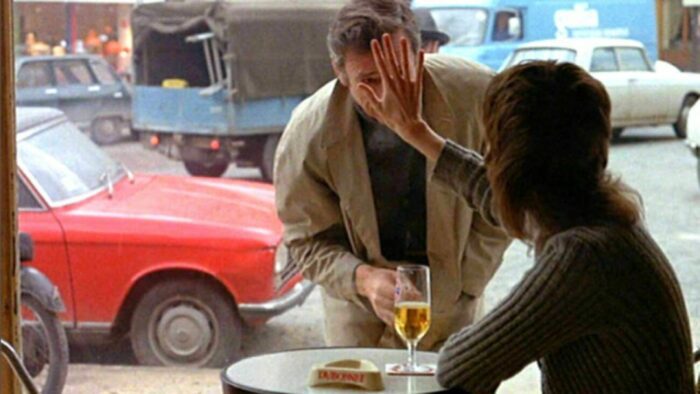

Tout va bien (Everything’s All Right, 1972)

Jean-Luc Godard’s 1970s films veered into highly politicized territory—endorsing not-so-subtle Marxist agendas. Yet, unlike modern polemical art, Godard was infinitely self-reflexive—ever mindful of his own complicity. In 1972, he teamed with Jane Fonda, one of Hollywood’s most outspoken stars at the time, to create Tout va bien (Everything’s All Right). Equal parts leftist manifesto and madcap comedy, documentary realism and cinematic fiction, the result is a fascinating encapsulation of a sausage factory strike, as mediated by an impudent American reporter Suzanne (Jane Fonda) and her auteur husband (played by Yves Montand, doubling as a New Wave director/ostensible stand-in for Godard himself).

Deeply cynical, Tout Va Bien looks at the futility of the 1968 France Revolution—offering an acerbic dissection of the ways new hierarchies organically emerge to fill the absence of former systems. We witness rampant hostility and factious divisions—between employers and employees, union workers and union leaders, male and female strikers. After the momentary triumph of working-class solidarity, it appears that gender and class rifts are reemerging with a fury.

What makes this critique of the radical failures of a proletarian uprising so complex is the way it also exposes and upends the entire mythological narrative-building around revolutions. One factory worker disparages Suzanne as being no more than an “expensively dressed reporter” “scribbling about [a poverty that] wasn’t [hers].” As a member of the media elite—the bourgeoisie class that spins yarns and stories—Suzanne symbolizes another mechanism of exploitation: plundering real-life inequality and struggle for the sake of spectacle and content. Clearly, Godard, as a storyteller concerned with social movements and struggles, this is a highly self-critical text—darkly questioning his underlying motives and modus operandi. — Paul Keelan

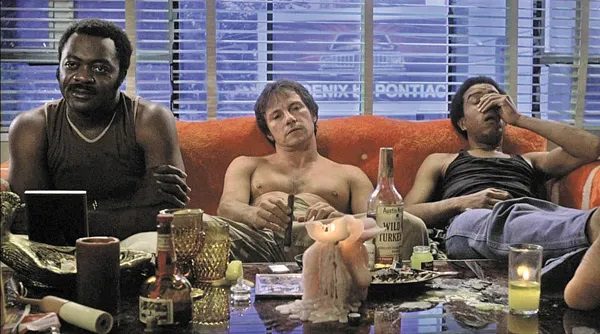

Blue Collar (1978)

Exploring the darker side of labor and unions, the directorial debut of Paul Schrader, Blue Collar is a fantastic drama of political and personal corruption set in the (at the time) thriving car manufacturing industry of Detroit. Starring Richard Pryor (in a rare and brilliant serious role), Yaphet Kotto, and Harvey Keitel as a trio of assembly line workers who concoct a plan to settle their financial pains and take revenge against their exploitative union by robbing the union office, only to find themselves under the thumb of the same hierarchical system they sought to strive against.

The cast bring real heft and humor to their roles. Despite their differing perspectives, backgrounds and personalities, the easy fraternal connections and loyalties between the characters are strongly established and painful to see cut down thanks to some superb writing from the Schrader brothers. As you’d expect from Schrader, the script is fantastic, articulate, tragic, angry and natural, and there are some brilliant moments of directing of some fantastic sequences accentuated by the foreboding sound design. The Detroit landscape is extremely well captured by the film’s vérite style, most notably in the nail-biting climactic car chase. It’s one of Schrader’s most keyed-in and irately political works, with a more sociological bent than his usual psychological portraits, but it resists dry polemic at every turn, resulting in a film that’s as thrilling and funny as it is angry and insightful. — Hal Kitchen

Norma Rae (1979)

Opening with a documentary-like set of establishing shots of the machinery, and the labor behind them, required to keep the O.P. Henley textile mill operational, Martin Ritt’s 1979 film Norma Rae wastes no time exposing the harsh realities of the working conditions of those in the mill and how their overall lives are thusly impacted. Despite sweating the days away working around machinery that causes anything from temporary deafness all the way to death to the employees, Norma Rae and many others can hardly afford to bring anything more with them to lunch than a single apple.

Living in a place so small that everyone knows when you “go into town” Norma Rae, played compassionately and tenaciously by Sally Field, feels stifled. She has no formal education, she always knew she was going to work in the mill. Both of her parents work in the mill and it’s practically the only employer where she lives. When she meets Reuben (Ron Leibman), a textile workers union of America organizer sent to her mill to try to form a union, she recognizes a chance to have a clear voice in her life and an opportunity to gain some autonomy within her monotonous factory existence. What Ritt and Field do so perfectly in the film is to make palpable the relation between one’s job and one’s sense of self and the impact of what one does for a wage on their life at large. As Norma Rae takes the journey of realizing how to assert herself in a meaningful way to the benefit of herself and those she both works with and shares her small town with labor takes on a whole new meaning. — Ashley Rincon

9 to 5 (1980)

Have you ever fantasized about a sudden change in power at the top of your company? Ever wanted to be your own CEO? Ever thought you accidentally poisoned your boss? No? Well, surely you’ve heard Dolly Parton’s “9 to 5.” Of course, the famous workers’ anthem isn’t just a song—it’s the bedrock of the 1980 screwball comedy of the same name in which Lily Tomlin, Dolly Parton, and Jane Fonda go from secretaries to CEOs overnight.

There’s a great deal of pot smoking, kidnapping, and animated wildlife in this workplace comedy, but it remains, at its core, a deeply pro-union film. Like Norma Rae before it, this film centers women as the agents of change in America’s mill-grinding work culture, but the three stars of 9 to 5 use far more outlandish methods of revolution. Infidelity, corporate espionage, even murder won’t stand in the way of lunch breaks and paid parental leave. There are few films as funny, charismatic, and outright anti-capitalist as 9 to 5. Before there was Sorry to Bother You, the biggest psychedelic trip in popular socialist film was helmed by three queens of pop culture. No one can say women never ran the world. — Todd Pengelly

Joe Versus the Volcano (1990)

Joe Banks (Tom Hanks) is sick. He’s told his particular ailment is a brain cloud, but, in actuality, he’s soul sick. The kind of sickness that comes from working at a meaningless job for four and a half years. It’s a feeling of being stuck doing something Joe hates while he waits for retirement so he can finally live. The only problem is that he’s been given six months to live and now his entire world is thrown upside down.

“I’ve been too chickenshit afraid to live my life, so I sold it to you for three hundred freaking dollars a week!” Joe exclaims as he quits his job in spectacular fashion. He’s not sure what his plan is for the numbered days he has left, but he’s sure he’s not going to waste them down in that depressing basement. In many ways, Joe’s brain cloud diagnosis is life-changing. It’s the jolt he needs to recalibrate his life. It’s so easy to get stuck working at a job that pays next to nothing and squashes your zest for life. There are few things in life as cathartic as quitting that job and choosing to live for yourself. Just ask Joe Banks. — Tina Kakedelis

Office Space (1999)

Through whip-smart comedy, Office Space called out all the feelings of corporate bureaucracy and workplace discontent with jest like no other comedy of its kind or its time. It stands united, yet diametrically opposed to the same push against monotony and empty employment achievement presented in the same year by David Fincher’s Fight Club. Between the two, Office Space is the easier pill to swallow.

Judge and his cast created a dream scenario of liberation from these woes. A silly bout of hypnotism lets Ron Livingston’s Peter Gibbons run his own schedule, shuck his responsibilities, gain newfound confidence, get the girl, and tell it like it is. The gusto (and memes/GIFs) coming off this movie is bottomless. The funniest part of it all isn’t so much watching Peter gallivant with a freed mind. It’s watching everyone else react to it with either quandary, emulation, or promotion. Seeing him inspire his co-workers (David Herman and Ajay Naidu) and fluster the low-key antagonists (Gary Cole, John C. McGinley, and Paul Willson) makes for better revolution material that punching each other and making anarchy soap. — Don Shanahan

Haiku Tunnel (2001)

Most films set in office landscapes are about alienation and existential dread. Working in a corporate setting is often an excellent backdrop for satirizing the dehumanizing nature of being a cubicle confined cog. Furthermore, the ennui seemingly inherent in modern existence is presented almost ad nauseum. Consider features like Office Space, Fight Club, In Good Company, Up in the Air: companies are evil, never fulfill individuals on a deeper level, and every human component of a corporation is treated as expendable. And the fact it doesn’t feel untrue is what makes this formulized symbolism seem so compelling. However, Haiku Tunnel takes a refreshingly different direction.

The film by autobiographical monologuist Josh Kornbluth shares the story of the best temp worker in business presented with the horrifying prospect of going perm. Offered a permanent position, Josh must make the leap from someone without attachments to an integral part of an office community. His various slipups and almost blatant attempts to get fired result more in nurturing, constructive criticism than anything hostile. Haiku Tunnel is a satire about finding connection where it seems the least likely, a relatable tale for the modern era featuring the other side of the corporate coin. — Jay Rohr

Monsters, Inc. (2001)

The beauty of good animation lies in its ability not only to connect with children, but with the adults who are always, begrudgingly, stuck on the couch watching over their children’s shoulder. That connection makes the repetitive nature of a child’s viewing schedule a little less dull for the parent, which is why I’d like to thank myself for picking such a fantastic movie to subject my parents to over and over again. Monsters, Inc., one of Pixar’s earliest staples and a childhood favorite of mine, remains one of the greatest examples of an animated film that connects with kids and adults.

For children, the connection is obvious: Monsters are funny and the adventure is silly. For adults, the connection is more tender. There’s the obvious humor dredged from work culture that only those old enough to work a nine-to-five will truly understand; but, there’s also a deeper current running through Monsters, Inc. It’s a film about bringing humanity back to the work place, about placing people over profit, about caring for the younger generations. Mike and Sully are great at their jobs, but they seek to fundamentally transform their business to save a single child. It’s a scary proposition, but it makes for a special film. — Todd Pengelly

North Country (2005)

Niki Caro’s excellent docudrama focuses on the true story of women in northern Minnesota’s mining industry in the 1980s. But what happens in North Country can happen anywhere—and all too frequently, does. Inspired by the first-ever class-action lawsuit for sexual harassment in American history—that of (Lois) Jenson vs. Eveleth Taconite Company—North Country’s plot centers on Josey Aimes (Charlize Theron), a composite character based on Jenson and others.

Aimes is faced with all-too-common a plight: fleeing from an abusive husband yet struggling to raise children on her own. Her job—working in a Taconite mine—might provide a way out of her situation, except the men who dominate her workplace treat her as a sexual object and lower-class citizen. The harassment she faces exists for no reason other than that she is a woman in a male-dominated workplace. As Aimes, Theron, of course, is typically excellent and Caro directs with confidence. North Country’s story may be rooted in the second-wave feminism of the 1980s but remains powerful and relevant even today. Long before #MeToo, it was the women of the Iron Range who stood up to rampant sexism in the workplace. — J Paul Johnson

Ingenious (2009)

Starring a pre-MCU Jeremy Renner, 2009’s Ingenious really speaks to the folks out there with non-stop ideas and dreams. They are our friends who are the thinkers, the scribblers, the Pinterest sharers, the tinkerers, and the amateur do-it-yourself specialists. They are more than just the ranter we know who starts sentences with “You know what I would do…”

Moreover, those ranters with the big ideas are one level of people that embody the good, old-fashioned American Dream. Ingenious‘s inventors Matt (Dallas Roberts) and Sam (Renner) are two guys that want to set the world on fire to better their lives and stamp their own ticket as self-made men. The movie shows the downs that go with the ups-and-downs of business. We see the failed ideas, errors in salesmanship, total loss, and, most detrimentally, the financial stress that follows people away from work. These downs have causes as well as cures. In getting that low, our guys are humbled by what’s really important and never lose the drive to keep their hope and dreams going.

In the business of original ideas and inventions, all it takes is one really successful idea to make all the hard work and previous failure worth it, even if that one idea is a talking bottle opener. The true story that Ingenious is based on is just one more chapter in that long novel of self-made American success stories where little dreams can become reality. — Don Shanahan

Made in Dagenham (2010)

Here’s a reminder for everyone: striking works. If you’ve been paying attention to the UK lately you’ll know how significant the pressure to strike for better wages, better benefits, and safer conditions has been.

Made in Dagenham is another true story of the labour movement at its finest, showing the impact of direct action as a force for real material change against a capitalist economy that puts profits over people. The 2010 film, with fantastic performances by Sally Hawkins and Bob Hoskins at its heart, tells the righteous story of the 1968 Ford sewing machinists strike in the Dagenham plant, which helped solidify equal pay for women nationwide.

Sometimes a little too cheesy and rote for its own good, but ultimately extremely charming, Made In Dagenham is like a hot cup of tea after a long day at work: cozy, warm, and just a little too sweet, not that it matters. Beneath all the big beehive barnets, rotary phones, and other charmingly quirky 60s nostalgia is a serious message in support of direct action and as part of the fight for women’s rights, of strikes and the working class labor movement as fundamental to British history. That’s something that—as British society is heating up toward a general strike, with more workers laying down their tools to demand better pay and conditions—is really worth remembering. — Riley Wade

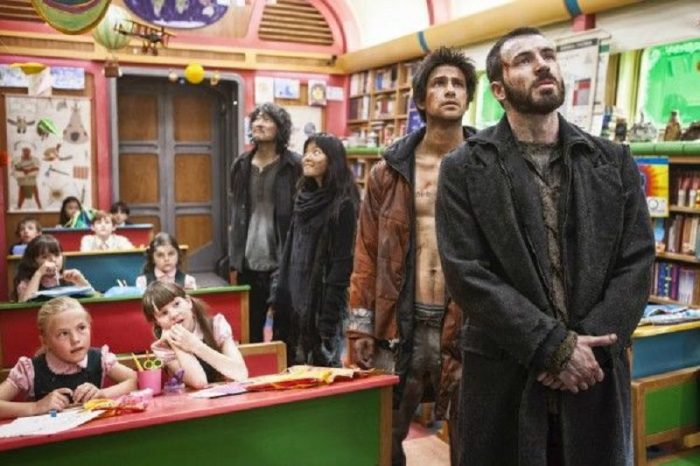

Snowpiercer (2013)

Snowpiercer is Bong Joon-ho’s breakthrough film for America audiences, and rightfully so. It finely balances its scathing if not a bit heavy-handed critique of conservative economic policies with mainstream blockbuster elements. Like Parasite, class conflict is at the center of the film’s allegorical narrative. Unlike Parasite, Joon-ho is working in a dystopian future, chronicling a revolutionary leader, Curtis (Chris Evans), as he spearheads a revolt on a post-apocalyptic train, which cannot disembark due to environmental conditions.

Adapted from a French graphic novel about climate catastrophe and the social aftermath, Snowpiercer is piercingly cynical—not only toward the train’s caste system, but also toward the cyclical and seemingly moot reoccurrence of social revolutions. Dividing the on-board passengers into a three-tiered hierarchy—First Class, Economy, and Freeloaders—and separating the haves and have-nots between the tail of the train and the front (near the engine), the system in play benefits a select minority and dehumanizes the vast majority. Supposedly, however, this inequality is necessary to maintain homeostasis (at least according to the conductor).

Boldly, Snowpiercer leaves viewers with more questions than answers—wondering A) if closed ecosystems can ever be sustainably equitable, B) if social stratification is part of the fundamental nature of reality, and C) if revolutionary acts are actually noble or merely pre-scripted byproducts of devious social engineering. By its final monologue, Bong Joon-ho even dares to put the film’s own function and potency under the microscopic—wondering whether the “blockbuster production” and “devilishly unpredictable plot” of a pre-orchestrated rebellion ultimately serves as another means of distracting/culling the poor. — Paul Keelan

Pride (2014)

It may be Labor Day in the US, but the working-class struggle is a nationless one, and as a UK-based contributor to 25YL I’d be remiss not to throw in a couple of my favorites. Here’s the first. Matthew Warchus’ Pride is, as Billy Bragg’s ending song beautifully portrays, about one thing above all: solidarity. Specifically it’s a kind of solidarity held between marginalized groups staring down at a society that loathes them.

A semi-fictionalized account of the actions of Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners in 1984, Pride is a film which breaks down barriers between blue-collar laborers and unionists (many of whom are also queer) and the queer community (many of whom are also working class)- instead uniting them in a singular struggle against the abuses of Thatcher and her homophobic, elitist Tory government. With some delightfully quotable comedy, and memorable performances, Pride never feels dire or tired, only angry and joyful and… well… proud. While it doesn’t get everything right (LGSM leader Mark Ashton’s commitment to communism is never discussed) the film’s unflinching political openness, dedication to joyous working-class solidarity, and righteous anger at classist conservative politics is a raised fist of feel good cinema that strikes truer today than it ever has. — Riley Wade

Paterson (2016)

Paterson doubles as the name of both setting and protagonist in Jim Jarmusch’s charming character study of a quiet New Jersey Transit bus driver and his wife. The film celebrates the working-class ideal of consistency – showing the poetic quality of proletarian labor and perfunctory routines. Each day, Paterson (Adam Driver) wakes to a vintage Casio alarm, puts on his uniform, packs his lunch, drives the same route, interacts with many of the same New Jersey locals, eats lunch by Paterson falls, drinks a single beer at the local watering hole, walks his dog, and enjoys a hearty dinner pie with his whimsically sweet and seemingly old-fashioned housewife. Throughout the day, Paterson scribbles poetry on the “beat”—jotting down stray conversations and passing observations. Gradually, his notebooks fill up with enchanting verses about his quotidian encounters.

Jarmusch has never been hesitant to use his films to pay homage to chic, hipster tastes. Here, Beatnik mythology and literary naturalism/realism is heavily featured. Blue-collar sensibilities seep into the textures and cadences of the film, not to mention Paterson’s lyrical musings. Both the setting and the tone are clearly influenced by the pre-Beatnik American modernist, William Carlos Williams – redefining mundanity by infusing it with meticulous attention and wonder. The plot is ancillary to Jarmusch’s aim to exalt everydayness through punctilious perception and language. With the backdrop of the post-industrial Paterson landscape, which once manufactured textiles and silks but now survives as a ghost of itself, Paterson works as a eulogy to a lost way of life—honoring a world where beatific splendors are to be found in the banal minutia of making ends meet. — Paul Keelan

Roma (2018)

The humility on display in Alfonso Cuaron’s Oscar-winning films begins in stark black-and-white opening on a fixed shot of cleansing water washing over detailed tile as it drifts across the view and empties off-screen. An unseen mop makes miniature waves in the present liquid. Holding further, the light draining sound begins to feel soothing as the water also creates a slight reflection to a quiet atmosphere. Lo and behold as the gaze widens, we learn this passing moment of domestic serenity is the scene of a woman cleaning dogshit off of a garage floor. It’s not cute little quick-smudge poodle droppings either. It’s voluminous hot mess excrement from a heftier dog. Oh, how the mood changes.

The young woman tasked with cleaning up this muck is Cleo, an inborn Oaxaca native and meek live-in housekeeper now working in Mexico City, played by first-time actress and Oscar nominee Yalitza Aparicio. The year is 1970 and Cleo’s needed duties range from a maid of household chores at daybreak to lights-out lullabies and bedtime stories at night.

The personal scope of Roma was built on the personal, influential, and selfless work of those who become caretakers. Cleo was modeled after Cuaron’s own indigenous childhood caretaker that he cherished and loved as the true woman who raised him. There’s no union or government oversight for work like that, yet it’s vital and life-changing. Like the more readily used fatherly term, mother-figures can be as important, if not more, than the real thing in every child’s journey touched by their servitude and devotion. By chronicling this working plight, the restorative and profound empathy is off the charts. — Don Shanahan

Support the Girls (2018)

Support the Girls is an empathic, sensitively told day-in-the-life-style portrait of Double Whammies: A Hooters-style sports bar specializing in “boobs, brews, and big screens.” Don’t be fooled by the film’s misleading visual aesthetics and marketing. Here, the cleavage-friendly attire serves as a Marxist symbol of capitalism reducing women to commodities who must show-off their goods to entice a middlebrow clientele. Throughout, Bujalski savvily usurps any raunch-com expectations – offering a humanely feminist portraiture instead. Breasts are but titillating window dressing: Seductively displayed with the subversive endgame of luring unwitting audiences into a deeply feminist, class-conscious exposé.

Light on plot, heavy on drama, and slathered in screwball bits, Mumblecore-wunderkind Andrew Bujalski delicately captures the ethos of low-wage solidarity—tapping into the camaraderie organically developed within back-breaking, ego-crushing, soul-destroying work. Shadowing the General Manager, Lisa (Regina Hall), over the course of a single shift, we witness the high-pressure stakes of menial-labor. Lisa must train bubbly waitress-to-be Maci (Haley Lu Richardson), juggle schedules, help Danyelle (Shayna McHayle) solve a child-care situation, fire an employee, deal with an inappropriate tattoo, call the cable company, apartment-hunt for an estranged husband, propitiate impertinent patrons, and throw a carwash fundraiser for a domestic abuse victim. Lisa resolutely dives into each imbroglio with a maternal touch, navigating ethical/interpersonal predicaments with tough and gentle love. She is protective yet demanding, stringent yet forgiving, nurturing yet judicious, compassionate yet direct.

Resonating far more potently than Hollywood’s revenge fantasies of performative feminism could ever dream, Support the Girls offers a biting neorealist slice of what countless women deal with in the workplace. It celebrates the way minimum wage workers form makeshift families to survive grueling, exploitative socioeconomic roles/conditions. Working together, the skimpily clad, oft-harassed, and ever-beleaguered waitresses overcome one indignity and quagmire after another. Here, the big victory is clocking out at the end of each day. Far from a screed, Support the Girls pays tribute to a more ordinary form of female empowerment—praising the importance of establishing a tight-knit community to look out for one another and occasionally share a rooftop swig before belting out a loud, heartfelt, and cathartic scream. — Paul Keelan

Sorry to Bother You (2018)

Not many films can deftly juggle multiple themes simultaneously covering a broad range of topics, but Sorry to Bother is an explosive surreal exploration of society’s deep-rooted flaws. More than a mere critique of capitalism, race, and social constructs, Boots Riley’s directorial debut is a scathing dark comedy about the modern human condition given those systems. In essence, this movie explores through surreal absurdity not only how toxic contemporary society is but how people embrace it pursuing the almighty dollar.

The film follows Lakeith Stanfield as Cassius Green on his descent into increasingly morally questionable choices as he ascends ever higher up the corporate ladder. This deceptively rags to riches story shows the terrible psychological and social cost of buying into capitalist ideas of success. Furthermore, it’s all done with a wild sense of style capturing the eye at every turn, spiced by an amazing soundtrack. Featuring fabulous performances by Stanfield, Tessa Thompson, and voicework from Patton Oswalt, Sorry to Bother You is that rare comedy which makes an audience laugh while trigging real insight. Humor does a solid job of sweetening the bitter blows delivered by this film. Yet, despite any roughness, it’s a wild ride well worth taking. — Jay Rohr

Parasite (2019)

The 2019 Cannes Palm d’Or winner and the historically unprecedented first foreign feature to win the Academy Award for Best Picture, Bong Joon Ho’s wickedly funny, smart, shocking Parasite won unanimous critical acclaim and box office grosses over $263 million on its tiny production budget of just over $10 million. Parasite places class conflicts at its core and asks us all to consider who exploits whom in a strictly stratified, gatekept society where the moneyed elite and the impoverished unemployed must coexist.

The film introduces us first to the plight of the Kim family—father Ki-taek, mother Chung-sook, daughter Ki-jung and son Ki-woo—trapped in a dingy basement apartment where they scrap at food and scrounge for a poached wi-fi signal. What’s on the outside for them? More relentless poverty, disrepair, and distress. The family’s home is fumigated, the portal between inside and out a porous one, the four of them reduced to vermin among rubble helplessly awaiting their own extermination. In a situation like this, one can understand their determination to survive.

But the Kims are a resourceful bunch—charismatic, clever, skilled, each of them with their own strengths. Through the slightest of opportunities, the son is first able to gain employment as tutor to the daughter in an upper-class family, the Parks, that mirrors the Kims’ own, except the Parks’ palatial home, with its glass walls, modernist décor, impeccable landscaping, and labyrinthine construction starkly contrasts with the squalor of the Kims’. Parasite cleverly asks its viewers to contemplate the degree to which the Parks’ wealth is earned, whether their family is in any way more deserving of their status and possession than the Kims’. Our societies divide and mark people by a social standing which, like a permanent stain or stench, never ever really goes away, no matter what series of events transpires. — J Paul Johnson

Emily the Criminal (2022)

Emily (Aubrey Plaza) is desperate. She’s drowning in student loan debt and the only jobs she qualifies are independent contractor roles that barely pay. Any efforts she takes to pay back her loan debt goes toward her exorbitant compounding interest. It’s no wonder that Emily takes up her coworker’s offer to hook her up with a high paying job that’s illegal. She takes part in a credit card scam and eventually parlays what she learns into her own criminal enterprise.

Emily the Criminal is more than a look at a crime ring operating in Los Angeles. It’s a quiet, non-judgmental look at how hard it can be to overcome crippling debt. The film is a scathing critique of capitalism that never seeks to paint Emily as a hero, simply a victim of odds that were stacked against her from the beginning. The American Dream has created a narrative that anything is achievable if you work hard enough, but that’s just not true. Emily the Criminal is proof of that. While not explicitly based on a true story, the story of Emily and the fundamental desperation she experiences is the reality of so many people. — Tina Kakedelis