Early next month, Sight & Sound will announce the results of its seventh decennial critics’ poll selecting the Greatest Films of All Time. While no one is likely to accept the results of this or any poll as definitive, the Sight & Sound polls serve as a reflections of the ebb and flow, wax and wane of individual films and auteurs’ reputations; they also serve, every decade, as an occasion for some spirited, even highly contentious conversation about the nature and purpose of cinema itself.

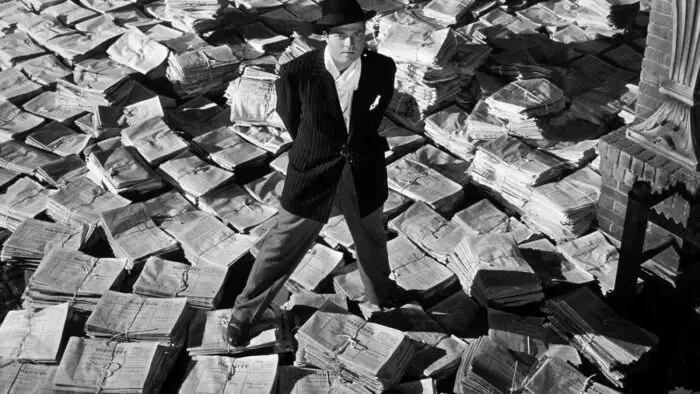

The last poll, conducted in 2012, sparked no shortage of debate, starting at the very top. For the first time in the 60-year history of the poll, Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane no longer sat atop the list; the 846 critics, scholars, curators, and programmers polled instead nominated Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo in its place. It had stealthily crept up the list from #11 in 1972 to #2 in 2002, just six votes shy of the top spot, helping to prove that film canons change, over time, albeit slowly.

The 2012 poll provided some other surprises: Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera jumped into the #8 spot from #27 a decade prior. John Ford’s masterful-if-contentious The Searchers staked a claim to the seventh spot when no Westerns had reached the top ten a decade before. Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now appeared for the first time at #15. David Lynch’s Mulholland Dr, the newest film listed in 2012, debuted at a respectable #28. Welles’ Touch of Evil, ranked #15 in 2002, dropped all the way to #57. Coppola’s The Godfather, ranked #4 when the poll counted both its and its sequel The Godfather II’s votes together as one in 2002, fell precipitously to #s 23 and 31, respectively, when counted separately in 2012.

At the same time, a number of well-regarded classics held firm in the Top Ten, including Yasujirô Ozu’s Tokyo Story, rising from #5 to #3); Jean Renoir’s La regle de jeu (The Rules of the Game), sliding from #3 to #4; F. W. Murnau’s Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans, from a tie for #7 to #5; Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey held at #6; and Federico Fellini’s 8-1/2 slid from #9 to #10.

The fact that the entire top ten consisted of films directed by men, most of them of Western European descent, did not go unnoticed, nor did the striking paucity of films directed by women or people of color. Only two films directed by women—Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles and Claire Denis’s Beau Travail—made the top 50 in 2012. Only one sub-Saharan film, Touki Bouki, made the list, at #93. In addition, no film directed by an African American made the list. No films from any South, Central, or North American country other than the United States were represented. The countries most frequently represented—France, the U.S.A., Germany, Russia, Japan, Italy—all have rich histories, traditions, and infrastructures on which their productions rest. Taiwan and Iran have a single film each, while others—say, Mexico, for instance, or South Korea—that have in more recent decades come to greater prominence based on the accomplishments of individual auteurs went without mention.

Those countries remain woefully underrepresented, as do films directed by women and Black, indigenous, and people of color. Some of that lack of diversity can be traced to the poll’s overwhelming focus on older films. It takes time, at least in the measure of this poll, to earn the status of a classic. Only three titles from the 1990s and two from the 2000s made the 2012 list. I would expect some of that to change in the 2022 poll if, again, by degree. The number of voters this year will have nearly doubled, making representation broader. In the wake of the George Floyd murder and subsequent worldwide protests as well as the Harvey Weinstein prosecution and #MeToo movement, more critical attention than ever has focused on efforts to prioritize the voices of those previously underrepresented both behind and on the screen.

The 2012 results also pointed to a lack of diversity in terms of genre. If Ford’s The Searchers was a surprise in the Top Ten as a Western, so too was Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera. Although it’s certainly not a traditional expository documentary, it’s the only nonfiction film in the Top Ten. (And Shoah is the only other documentary film in the top 100.) Overall, only a handful of westerns show up on the 2012 list, near the bottom of the top 100. One might say the same about melodrama: you have to scroll to the very bottom of the list for Sirk, Ophüls, and Fassbinder. Comedies? Other than Chaplin’s and Keaton’s two apiece, only Some Like It Hot and Jacques Tati’s incomparable Play Time show, at #42 and 43, respectively.

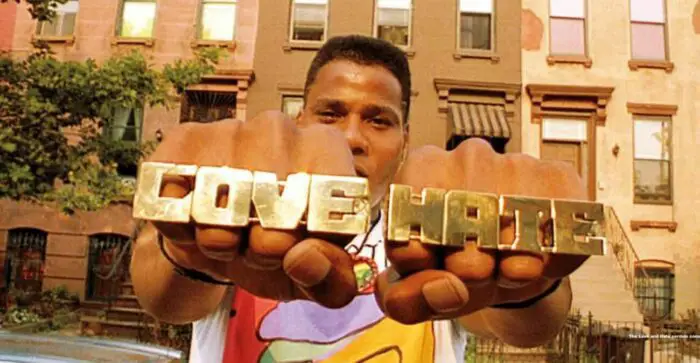

Overall, I’d expect the 2022 poll to feature at least some greater diversity in these regards. I’d expect to see Spike Lee make the list, and deservedly so. While it may be distressing to note that Do the Right Thing took on an additional weight of prescience in the wake of the Floyd murder (and scores of others not unlike it), his film remains a singular accomplishment, bright, touching, idiosyncratic, funny, daring, meaningful, and resonant, absolutely deserving of a spot among the very best films and filmmakers. Indeed, a few of his films and other African American directors might—should—make this list for the first time. If his riotous, challenging Bamboozled should, that’s a sign the times are indeed a’changing.

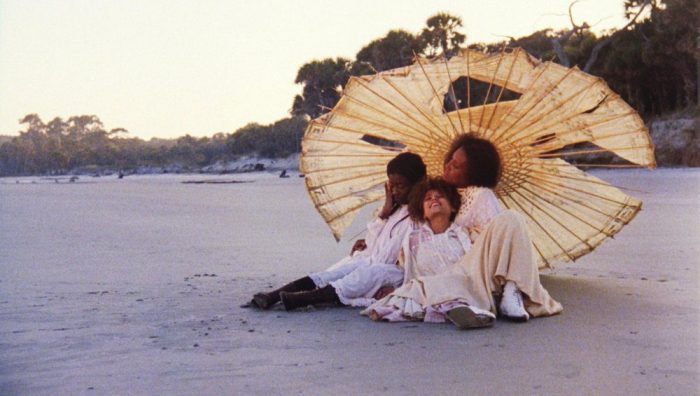

How is it even possible, meanwhile, that only two films directed by women appeared on the 2012 list? One might look to the past (how about Agnes Varda’s Cléo de 5 à 7, Larisa Shepitko’s long-overlooked The Ascent, or Jane Campion’s The Piano?) or the more-recent present (maybe it’s time for an Ava DuVernay, Dee Rees, Julie Dash, Emerald Fennel, Ana Lily Amarpour, or Patty Jenkins) for some potential candidates. Will the nearly 1600 voters recognize the remarkable accomplishments of filmmakers from Mexico, South Korea, and a dozen other countries whose work has never before been nominated?

The 2022 results will be announced December 1st, with results and commentary of both the critics’ and the directors’ polls appearing in a double issue of Sight & Sound available to subscribers the following day and on newsstands December 5th. Will those results reflect a significant change at the top of the rankings as they did a decade ago? Will the list in full better reflect the accomplishments of a wider diversity of filmmakers across the world?

Join us here at Film Obsessive next month for an update on and analysis of the 2022 poll results. And in the meantime, feel free to sound off in the comments. What would be your Top Ten? What do you think the 2022 results will reflect?

And for the record, here is my Top Ten. Unfortunately, I wasn’t asked to vote by Sight & Sound. Though if they keep doubling their number of respondents, I may have to wait only another decade or three! These are not my predictions, but the films I would vote for if given the opportunity. For the record, I am a longtime cinephile who loves, really, most of the films listed in the polls to date, and I have few quibbles with any of the films named in the most recent top ten.

- Do the Right Thing (Spike Lee, 1989). I have often told students (and long before the Floyd murder and protests) that this is the best film of all time, despite what polls and critics might say. I once thought it might date itself as the years passed, but having watched it at least once every year since its release, I find Spike Lee’s masterful race-relations drama simply gets better and better, even if the tensions it examines are yet to be resolved.

- Citizen Kane (dir. Orson Welles, 1941). That Welles zagged from theater and radio to film at age 25 to make a film that changed cinematic history with a dizzying array of inventive techniques—and a grand indictment of unfettered capitalism—still works for me. Every rewatch remains a new and vital experience.

- Psycho (dir. Alfred Hitchcock, 1961). I get those who claim Vertigo to be the best Hitchcock. It may well be the most sophisticated and fully fleshed out of his films. But I prefer the grimy, shocking, slightly schlocky Psycho, a film that took cinema down into the dirty shower drain of blood and greed. Its brilliant editing, music, cinematography, and lead performance opened the door to high-concept B-film content that shaped the next half-century plus of cinema.

- Tokyo Story (dir. Yasujirô Ozu, 1953). “Isn’t life disappointing?” ask its lead, the dutiful daughter-in-law Noriko. And we know the answer. But it’s also circuitous, marvelous, and ironic. It’s Ozu at his peak and perhaps the greatest tale of aging in cinema. I can’t quibble with its ongoing ascent in the critics poll from decade to decade; nor can the directors polled, who granted it the #1 spot in their ranking.

- Le Mépris (aka Contempt, dir. Jean-Luc Godard, 1963). Godard was well represented in the 2012 list with four films in the top 100 if none in the top ten. You might pick any of a dozen of his films, but I will advocate for the breathtaking Le Mépris, a star study that enlisted Brigette Bardot to torment Michel Piccoli in a loose, canny adaptation of an Alberto Moravia potboiler. It’s an endlessly fascinating, turbulent, creepy tale of desire, ennui, and greed.

- Man with a Movie Camera (dir. Dziga Vertov, 1929). A film that displayed with amazing, unrelenting energy what a camera—or a person with a camera—might do or make. It broke all kinds of rules and opened up 20th-century cinema to endless possibilities.

- The Ascent (dir. Larisa Shepitko, 1977). Too long and too unjustly unknown beyond her native Russia—and too tragically the victim of an accident that took her life at the young age of 42— Larisa Shepitko braved brutal conditions to make The Ascent, on the surface a simple battle film but at the same time a deeply allegorical tale of sacrifice and betrayal.

- Come and See (dir. Elem Klimov, 1985). This devastating, gruesome, harrowing war tale plunges viewers into the horrors of war close-up through the eyes of a young boy. Little Flyora, infatuated with guns and eager to enlist, seems to age an eternity by the film’s end: unlike most war films, nothing about Come and See can be said to ennoble war’s pursuits or glorify its battles.

- Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (dir. F. W. Murnau, 1927). An amazing, expressive synthesis of silence and sound, Europe and Hollywood, melodrama and realism, traditional and modern, in a simple tale of good and evil, made at the very precipice of a technical revolution that would change cinema forever. Sweet, good-natured, and evocative, Sunrise feels still like an ineffably frozen moment in time, forever fresh and full of life.

- The Rules of the Game (aka La règle du jeu, dir. Jean Renoir, 1939). Renoir’s pre-war satire of the romantic hijinks of the French upper- (and lower-) class taught Orson Welles all he needed to know about the moving, probing camera that would animate Citizen Kane. It also made for a riotously comic, moving, and insightful parable of honor and betrayal that would inspire and influence a subsequent generation of filmmakers.

Honorable Mention: For what it’s worth, there’s more than a few films I wouldn’t mind seeing make the list of 100 Greatest Films of All Time. Those would include, in absolutely no particular order, Oldboy, Parasite, Pan’s Labyrinth, The Piano, All That Heaven Allows, City of God, Double Indemnity, In a Lonely Place, Black Girl, Mad Max: Fury Road,Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, The Act of Killing, Brokeback Mountain, The Bride of Frankenstein, Logan, WALL*E, and Borat! Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan.

Great article and one which will send me off to explore many of the films you mention. But as an Englishman I noticed the glaring lack of films from the UK. Glad to see my all time favourite (A Matter of Life and Death) represented, along with another Powell and Pressburger classic, Colonel Blimp, but then only Lawrence of Arabia making a grand total of 3? Was it something that we said? No Red Shoes? No Great Expectations? O Lucky Man? Kind Hearts and Coronets? The 39 Steps? Odd Man Out? Get Carter? The Long Good Friday? Life of Brian? Dead of Night? Oh well – you get my drift….