Beavis and Butt-Head Do America hit theaters on December 20, 1996. I was 16 years old. I first encountered Beavis and Butt-Head a few years before on MTV’s Liquid Television and followed them as they got their own show. I remember them yelling “fire!” and the controversy that sprung up around it at the time. Many “family values” types were up in arms, putatively worried about Mike Judge’s show corrupting the youth. And they won, insofar as running gags about fire were removed from the show not just for future episodes, but retrospectively.

Beavis and Butt-Head Do America calls back to this, of course, as the pair watch the monitors at the Hoover dam—they need more shows about fire. It also plays with the notion that the duo exerts a nefarious influence, as when Butt-Head appears demonically in Beavis’s hallucination.

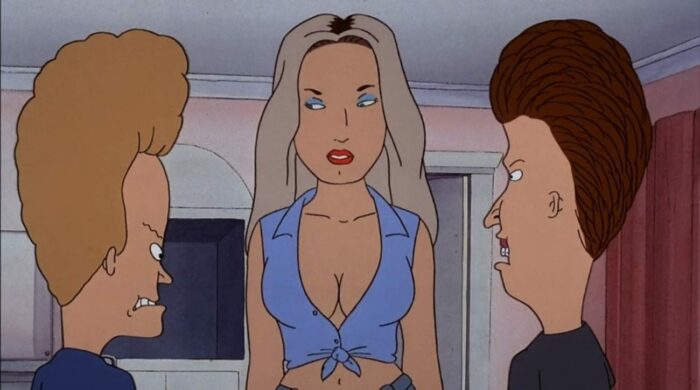

It is somewhat strange watching the film again now, 25 years later. There are both the changes in myself and the shifts in the culture to grapple with. It’s hard to see Beavis and Butt-Head Do America being made now, or all too easy to imagine the new kind of outraged reaction it might elicit. Here is a film that centers around the protagonists trying to “score”—the plot device of their missing TV is actually a bit tangential. Even the opening scene—which parodies kaiju but always mostly put me in mind of the arcade game Rampage—features a certain objectification of women.

The film’s main plot involves Beavis and Butt-Head somehow thinking that Muddy (Bruce Willis) is hiring them to have sex with his wife Dallas (Demi Moore) and traveling across the country to pursue this aim. Of course Dallas has hidden a bioweapon in Beavis’s trousers, and the Feds are in pursuit, ramping up a fairly ridiculous mid-90s film plot.

But while that plot climaxes with a showdown with Cornholio-Beavis that ends with his pants being flung into the air, only for Butt-Head to ultimately hand over the bioweapon (both throughout wonderfully unaware of what is going on), the crescendo of the film truly lies in the rant Beavis gives on the tour bus about how they’re never going to score. It’s an expression of adolescent sexual frustration I want to continue to read charitably (and can relate to), but from the perspective of 2021, it might start to feel like it veers a bit too close to the rhetoric of incels for comfort, much as our friends Beavis and Butt-Head are definitely not that.

Given all of that, I can’t say the film holds up for me now. Most of the enjoyment that I got from revisiting it stemmed from a certain kind of nostalgia—I more remembered when I thought the Cornholio bit was funny than I found it funny now, for example—but I do find myself thinking that there is perhaps something a step deeper worth thinking about that lies in that nostalgia.

Beavis and Butt-Head are crass and juvenile, sure, but this was always the point. Their humor is moronic, but it strikes me that the power of the bit always lay in the fact that we nonetheless do not laugh at them so much as with them. This is gross, awkward pubescence on display, but it isn’t shamed, and there is something to be said for that.

There has always been something almost meta about the humor of Beavis and Butt-Head. They are misfits, but they are not cool. No one has ever wanted to be them. But why, then, did we parrot them, if not because the cartoon itself gave a freedom to give voice to a kind of adolescent id?

It can seem as though there is a real puritanical streak among the youth of today, with worries from every quarter about whether things are problematic and a default moralism at play in the reading of film and TV. While I’m as much for delving into the political or ethical stakes of a work of art as anyone, to be clear, it’s the tendency towards a kind of oversimplification that bothers me, as though movies are all supposed to have some consistent kind of message that can straightforwardly be ascribed to the filmmaker.

Perhaps I have merely been spending too much time on Twitter.

Nevertheless, what is striking is the extent to which no one could think that Beavis and Butt-Head are being put forth as exemplars to be emulated if they approach the work with any level of sophisticated thought. That is just clearly not what is going on here. Neither are they the object of criticism, even though they bumble their way through the plot of the film wreaking havoc on those around them while at the same time emerging unscathed. If Beavis and Butt-Head Do America holds anyone in a critical light, it would be the Feds and ultimately Bill Clinton, as he rewards the titular duo at the end of the film. Never mind that an innocent man has had his life destroyed, and we know that as an audience even if we don’t particularly care, the point is that the powers that be are woefully out of touch and don’t know what they’re doing (see the running gag about giving everyone a full cavity search).

They don’t know and they don’t know that they don’t know—they think they do. And while I can’t quite bring myself to claim that Beavis and Butt-Head at least know that they don’t know, drawing some strained comparison to Socrates, I will nonetheless assert that there is a certain authenticity that they present. They are not just young but stupid and puerile, and yet expressions of a genuine joie de vivre even if as it relates to “whacking it” in Mr. Anderson’s shed. Know thyself.

Speaking of Tom Anderson, it’s impossible to miss the similarity between his character and Hank Hill, which extends far beyond the fact that Mike Judge voices both. There is a real compassion that runs through Judge’s work, which is perhaps most clearly on display in King of the Hill, but which we should see in Beavis and Butt-Head as well. Not a compassion for Mr. Anderson, necessarily, mind you, as he serves as the butt of a joke with his arrest in Beavis and Butt-Head Do America, and generally within the show, but primarily with regard to Beavis and Butt-Head themselves. They are cartoons and there is something almost outlandish about them, but at the same time, they are deeply human. Perhaps we are prone to want to repress the aspects of ourselves that they embrace, but we risk a certain kind of bad faith if we try to pretend they are not there.

We identify with Beavis and Butt-Head because they give a free and unashamed expression to our juvenile and prurient selves. Although everyone may not connect to it, there is something potentially cathartic in this stupidity and the fantasy of it passing without real-world consequence. Beavis and Butt-Head are never punished; they always skate free. They can jump from the back of a moving car and emerge unscathed.

Of course, that doesn’t go for those around them—from Tom Anderson to the massive wreck that occurs in the wake of that jump from Muddy’s trunk—but in this regard, we might almost read the lesson to not actually be like Beavis and Butt-Head, even as we enjoy vicariously through them.

I worry whether there remains sufficient space for this kind of enjoyment in 2021, or if we’re just too weirdly serious about everything. Perhaps this is why there are plans for a sequel, but I wonder how it will land. I struggled to still enjoy Beavis and Butt-Head Do America now to the extent that I couldn’t avoid thinking critically about its sexual politics (though I did still guffaw at Cloris Leachman’s Old Woman character talking about slots). Further, while the implication that all adults (particularly those in positions of power) are clueless and inept continues to strike a chord, I find myself now a bit more apt to cry than laugh about it.

But surely the free expression of adolescent impulses is preferable to its repression, and that free expression, moronic as it is, is what Beavis and Butt-Head represent. It’s not a matter of bolstering problematic patriarchal norms—such a reading would be too facile—but about fostering a sense that it is safe to not fit in with any norms at all.

That would be cool.

I remember watching it when i was 4, yikes! I rewatched it last week and then I realized, just like The Simpsons and their predictive programming, same with the movie. The deadly virus? Yup! All in the movie!

Thanks! And yeah, it was interesting to revisit it now

Excellent review! I have so much nostalgia for Beavis and Butthead, but for some reason haven’t got around to revisiting this movie. I think my reactions and experience would be similar to yours.