In a 1973 interview with Gene Siskel, François Truffaut famously claimed “Every film about war ends up being pro-war.” And as early as 1960 he had taken the position that “to show something is to ennoble it.” Surely his perspective applies to a film like Apocalypse Now, with its lavish spectacles of combat. Most war films, even ones with anti-war sentiments, tend to support Truffaut’s point: in depicting combat with all the technique available to cinema, war films seem so often to glorify that which they decry. From the silent Wings and early sound-era All Quiet on the Western Front to the modern anti-war polemics of Francis Coppola and Oliver Stone, even ostensibly anti-war war films depend on cinematic spectacle to astonish viewers. Truffaut passed away a little less than a year before the release of Elem Klimov’s extraordinary Come and See in 1985; the Russian director’s film might have given Truffaut pause to reconsider his claim.

The simple phrase “war movie” suggests, on its surface, an emphasis on combat, but not all war movies take place on the battlefield. Films as diverse as The Grand Illusion, The Best Years of Our Lives, Coming Home, and Before the Rain are among those that eschew the clichés of military maneuvers and tactical objectives in order to explore the psychological trauma, emotional impact, ecological devastation, and moral quandaries faced by those impacted by war. Some, like Courage Under Fire, focus more on a post-mortem investigation; others, like The Ascent, on the ethics faced by prisoners of war; and still others, like Dogfight, hardly on combat at all but instead on the machismo and misogyny of military enculturation.

Come and See includes next to no combat in the conventional sense. Instead Klimov depicts the journey of a young boy’s eager enlistment and subsequent maturation as he witnesses the horrors of Belarusian genocide in World War Two. Its subjective sound design, intentional editing, and compelling cinematography create a hellish, sobering, devastating journey for its young protagonist. In the process, Come and See makes for as anti-war a war film as is humanly possible.

The narrative begins with a gun. Or, rather, a search for one, as in 1943 young Flyora, a Belarusian boy hoping to be conscripted into the partisan resistance movement, plays at war by digging for a gun in the sands near his house where an earlier skirmish had taken soldiers’ lives. A village elder warns him—in the sense of a Proppian interdiction—not to, but Flyora finds his gun and soon finds himself conscripted to the partisans. Anton Chekhov, of course, held that a rifle revealed in the first act must go off by the third. He was speaking figuratively, as his principle applied more broadly to any narrative function of property. But in fact, Flyora will fire his newfound weapon, though not until the film’s very end, and then not at an enemy combatant but at an idea represented symbolically.

Flyora’s wartime experience is largely as witness to atrocity, and Klimov’s narrative focuses on a series of episodes that increase in their intensity and scope. As much as young Flyora desires to engage in combat, fate will not allow him that privilege. Ordered at one point to remain behind the marching unit, Flyora is suddenly attacked by German paratroopers and dive-bombers whose explosions result in partial deafness. His injury impairs his judgment as he and his friend Glasha, a nurse also left behind, seek shelter and search for survivors.

Klimov’s intentionally experimental sound design aligns viewers’ perspectives with Flyora’s. Instead of a clear and faithful reproduction of the sounds of mortar shells and explosions, Klimov’s sound design—created by the director and sound engineer Viktor Mors—replicates subjectively the atonal cacophony of muted, distorted sounds Flyora’s damaged hearing interprets. A high-pitched whistling over a low orchestral drone, mixed with muffled ambient sounds and Flyora’s labored breathing, makes him unable to discern attackers or process information. Where some war films lay out geography with specificity, the sound design here instead registers the horror, trauma, and confusion of the young boy’s experience.

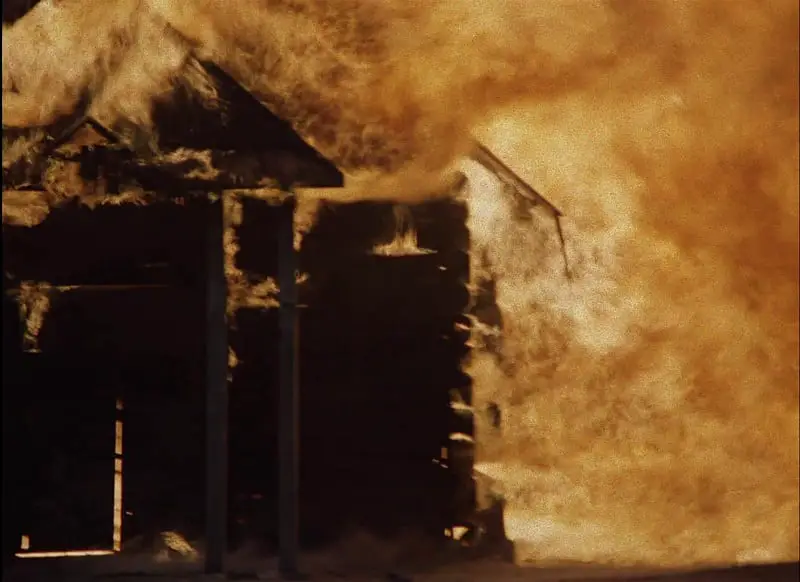

When later Flyora finds himself captured and taken to the village of Perekhody, an SS unit and Ukrainian collaborators occupy the village. Flyora is forced alongside the villagers into a wooden church. In this sequence Klimov’s artful continuity editing depicts the horror of genocide as Flyora escapes the throng through a window, only to witness the church’s burning—and that of hundreds of Belarusians—inside. Klimov’s is a straightforward, effective use of the simple cut, from the panicking masses inside the church to exterior shots from Flyora’s perspective outside. In the process of filmmaking, the production consists of interior shots of a group of panicking villagers inside and then later exterior shots of a burning (but of course empty) building. But in the edit Klimov makes Flyora—and us viewers—feel the excruciating anguish and horror of mass execution through this sequence of simple shot/reverse shot and point-of-view shots.

Is “to show something to ennoble it” as Truffaut first claimed? This scene and Aleksei Rodionov’s cinematography throughout suggest otherwise. There are images of haunting beauty, especially in the early forest sequences where Olga Mironova’s Glasha appears like a fairy nymph framed by a rainbow. Later, strafing mortar fire lights the dusky sky like fireworks. But for the most part, Come and See’s distinctive cinematography aims to disrupt and immerse viewers in the horrors Flyora witnesses.

The frequent use of centered close-ups of characters facing the camera directly— the village elder, Flyora’s young playmate, the nurse Glasha, a second girl with whom he escapes the barn in Perekhody—are held in long takes that confront Flyora with the harsh truths of wartime. Flyora’s face is framed more than a half-dozen times in haunting, harrowing close-ups that chart the toll his experience takes on him as he seems to age decades in the week or so the film’s story-time depicts.

Rodionov’s cinematography in these close-ups focuses on stasis as each of these long takes can range from six to fifteen seconds, creating a rare intimacy between Flyora and the others he meets. Late in the film, two split-diopter shots connect Flyora with other youth—first a fellow escapee, now the bloodied victim of rape and assault by the Germans, and then another young Partisan who looks much like young Flyora in silhouette. Though held more briefly, these split-diopter shots reinforce Flyora’s connection with others similarly impacted or traumatized by the war.

In opposition to the stasis of the close-up and split-diopter shots are the lyrical, gliding Steadicam shots through the forests and villages that make Flyora’s experience feel almost ethereal. These shots glide through and out of doorways, between trees, through crowds, and over fields, following every step of Flyora’s experience. Come and See’s cinematography throughout is remarkable, always in service of Klimov’s story and never serving to glorify a cause, fetishize violence, or in any way ennoble the war it depicts.

For all the heightened, immersive, ethereal experience Come and See’s cinematography creates, in its final minutes the very real consequences of the Holocaust crash in. Having witnessed his fellow Partisans execute a group of SS officers, Flyora begins to follow his colleagues out of the village when he spots a framed image of Hitler “The Liberator” in a puddle. Flyora has yet to fire the rifle he found in the film’s first minutes and has carried nearly continuously throughout. The photo triggers something in Flyora and a montage of black-and-white documentary photos and video of Holocaust victims begins. These are, of course, among the most haunting, devastating, horrifying documentary images in human history. They are not easy to witness.

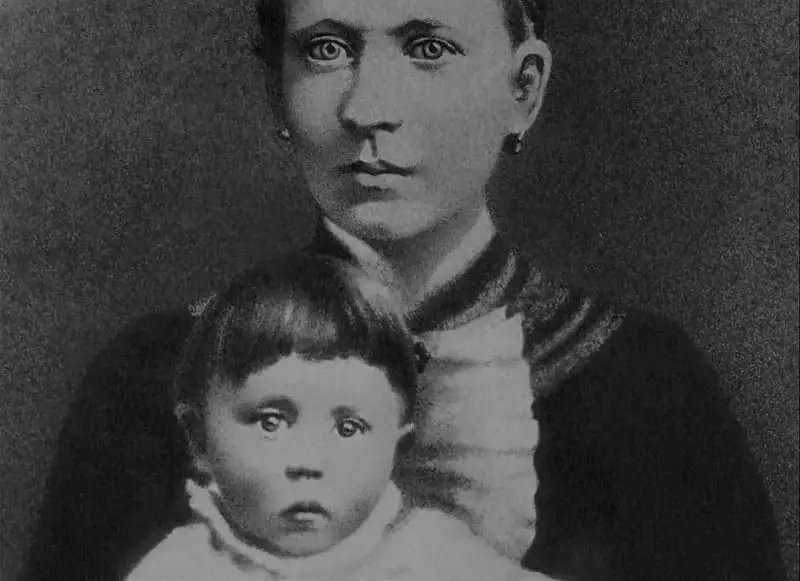

As Flyora reels and raises his gun, the images continue—of Holocaust victims, Nazi stormtroopers, of the Nuremberg rallies (repurposing Riefenstahl’s footage from Triumph of the Will), and of Hitler’s atrocities. Unlike the rest of the film, the historical images of Hitler’s reign of terror fly by in a fever dream and a breakneck pace, most images lasting less than a second—and in reverse-time. Enraged, Flyora takes aim at Hitler’s image and fires away. The images continue, firmly establishing time is reversing, up until Flyora sees an image of Hitler as a baby.

The use of the image of baby Hitler raises the philosophical conundrum: is it ethical to kill one infant to save millions of lives? Could killing Hitler as a baby avert his rise to power, reign of fascism, World War II and its attendant genocides? The question is a version of what was dubbed the “trolley problem” by Judith Jarvis Thomson in 1976 and later the subject of considerable scholarship in ethics, in which a person must to choose between a speeding trolley certain to kill a group of people or diverting its course to kill one, with dozens of different variations of circumstances.

Klimov for a time even considered titling an early iteration of his planned film “Killing Hitler” before instead using the biblical phrase “come and see” from the Book of Revelation as an invitation to look upon the destruction caused by the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. (That title would have seemed to belong to a more literal dramatization of something like the Operation Foxley assassination attempt than Come and See’s more metaphorical approach.)

Upon witnessing the image of baby Hitler, though, Flyora lowers his rifle. His choice is clear: he wouldn’t kill a baby Hitler, even to avert the atrocities his reign committed. Though matured and traumatized by his experience, he is not a cold-blooded killer, and the only time he has fired his weapon of war was at a framed picture in a pool of mud. (A 2015 survey of New York Times readers conducted on Twitter had 42% of respondents saying “yes” to the question “Would you kill a baby Hitler?” Thirty percent said “no” and 28% were not sure.)

But the ethical dilemma Klimov poses here is no mere abstract philosophical exercise. His is a film dedicated to the victims of Belarusian genocide. Estimates vary as to the exact number, but over five hundred thousand died in Grodno, Brest, Minsk, Baranovichi, Pinsk, Khatyn, and other cities in Belarus. Klimov’s ending title card bluntly informs: “628 Belarusian villages were destroyed, along with all their inhabitants.” Come and See depicts just a small percentage of the devastation wrought by the Nazi occupation of Belarus, but with an emphasis on one young recruit’s experience.

The film’s script was co-written by Ales Adamovich, who, while a teenager and student, became a partisan unit member in 1942, just as the Nazis systematically began to torch hundreds of Belarusian villages and exterminate their inhabitants. His experience as a messenger and guerilla fighter was central to the script. So too was the choice of a lead actor to portray young Flyora, whose performance would be central to the film’s success but whose psyche would be subject to the traumas the script depicted. Young Aleksei Kravchenko, just 14 when cast, recalls in an interview having auditioned only to accompany a friend, then bursting into tears there when asked to contemplate his mother’s death. His audition won him the role and his performance Klimov’s respect.

Kravchenko had, as he said in the same interview, “no experience but only eagerness”—making him perfect for the role of Flyora, who too had eagerness to serve but no experience. Fascinatingly, the most harrowing part of the shoot for Kravchenko was not the slog through a muddy, parasite-filled bog but being trapped in the Perekhody barn. Even during the safety of the production, he knew from the collective cultural memory of his fellow Belarusians what such entrapment meant: “I nearly lost my mind in there,” he recalls.

Come and See took nearly a decade to bring to fruition. Klimov had begun work in 1977, the year his wife Larisa Shepitko finished The Ascent. At first, the screenplay was disapproved by the State Committee for Cinematography and then Shepitko was killed, tragically, in a car accident in 1979. Klimov took over the direction of her last intended film, Farewell, and then an elegiac tribute to her entitled Larisa following. By the time he was ready to shoot Come and See, the censorship board had relented sufficiently to proceed. Come and See, like The Ascent, is a war film that focuses less on combat and more on the potential of war to impact those who witness and survive its horrors. The film would be Klimov’s last, but it makes for an eloquent testament to his art.

When François Truffaut claimed no war film could truly be anti-war, Klimov was scarcely known outside his native Russia. Had Truffaut lived just one more year to see it, he surely would have been astounded by Come and See‘s harrowing, truthful tale of a young soldier’s coming of age, its artful use of cinematic technique, its shocking use of documentary footage, and by its anti-war sentiments. Truffaut might have even reconsidered the position he had held for the better part of two decades. If there were ever a film to document the horrors of war without ennobling them, that uses every means of cinematic storytelling to condemn its subject, it must be Elem Klimov’s incredible, arresting, and incomparable Come and See.