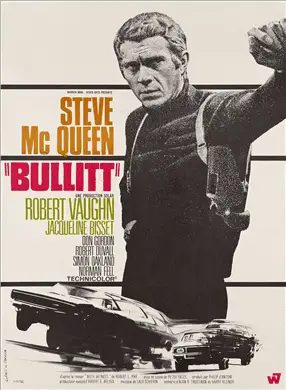

Anti-heroes have a way of holding a mirror up to their audiences. Whether a viewer likes it or not, these less than perfect creations reflect society’s true identities over the all too common unattainable ideals that accompany any decade. 1960s cinema was grappling with these imperfections, as filmgoers and filmmakers alike stared into a void left by the progressively insignificant traditional hero complexes. The times demanded a new sense of authenticity which could confront previously established norms for a protagonist without giving way to false notions. It comes as no surprise these inspirations would bring about one of film’s best characters, Frank Bullitt. This anti-hero is coolness personified in an increasingly complex vision of the decade’s criminal natures. The first glimpse of Bullitt doesn’t come from a fast-paced chase or bloody fight. Instead, the lieutenant is fast asleep and completely unaware of the difficult story that awaits him. It’s the last time the character is seen in this state and a vivid reminder that society itself was undergoing an awakening it couldn’t space.

Gazing At A Barbaric World

A violent landscape was encircling the very vestiges of 1968. Crime rates were growing across the board and major events throughout the year were bringing bloody aftermaths into focus. These actions created ripple effects that were shattering the comfortable perceptions of what it meant to be safe for every part of society. Those same details found their way into the dramatic fiction once reserved for noir dramas. The undercurrent that was hidden away from the respectable suburban hideaways splashed across the screen in unwavering detail, as Lieutenant Bullitt dealt with a truth that many were not yet ready to face. Nothing personifies the film’s harsh realities like Bullitt’s up-close view of his young partner’s fight for life. The great anti-hero watches helplessly as Stanton writhes in agony with every blistering pain that pulses through his body. It is both a confrontation of the lost souls he usually dismisses and a stark wake-up call to everything he chooses to ignore.

The sequence itself stems from an equally disturbing moment where both Stanton and the faux Mr. Ross are callously gunned down in a lowly motel room. There is no chance to look away or ignore the unfolding brutality of watching two people grapple with their mortality. Without the anti-hero on the scene, the film pushes the audience to experience the moment without a grand saving gesture to remedy the onslaught. It decidedly offers up the realization that no-one is coming to save the two characters, just as no-one was going to save a society tilted on its own morality axis. Using blood and sound to permeate the sequence only heightens the stark nature of its meaning. This deliberate method is a pointed criticism of other fare that relegated shooting and violence to a bloodless act that could easily be compartmentalized in the viewer’s mind.

The Unfamiliar Culture Of Strangers

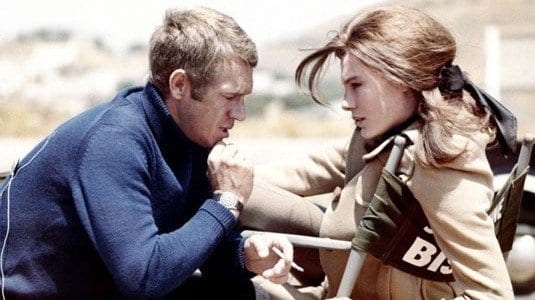

Being an outsider has always been a scary proposition. Whether you’re the kid who never quite fit into the cliques or the adult who struggles to find answers, it’s a daunting task to stand on the outside looking in. When it comes to Bullitt, he accepts the title with a mix of resolve and toughness. It’s obvious that he wants no part of Chalmers station in life and the denizens that inhabit it. He listens to guests blather on about their inconsequential stories, knowing that something far darker was found in the things he saw every day. They stay blissfully unaware of the life unfolding around them with a virtual glee that could easily be mistaken for naiveté, yet ultimately looks more like willful ignorance. There is a sense of relief when Bullitt can excuse himself from the crowd and back to the assignment at hand. As the film progresses, he only gives girlfriend Cathy a glimpse of the what his perceptions about the interloper role really entails. In a table-turning moment, she becomes the encroacher while viewing the lifeless body of Dorothy Simmons. Her shock brings to life the voice of the audience whom themselves feel like outsiders among the harsh truths being presented in plain sight. Cathy’s confrontation of Bullitt afterwards is a discussion with the viewers as much as it is with him about the disconnections that we tolerate towards cruelty.

Everything Unsaid

Sometimes the best way to make an impact is by saying nothing at all. While much of the 1960s carried its own boisterous sound and fury, there was a silent presence that held a sense of calm among the unrelenting chaos. Frank Bullitt is a man of few words, but each one carries an unrivaled weight and importance that others betray with long-winded hyperbole. A look, just a glance, is all it takes to truly make the connection with the audience in a way that other characters’ brief diatribes could only hope to achieve. Without warning, the sincere expressions create the connection with an audience that is almost unbreakable as the story progresses. Among it all, there is a sadness and surrender behind those alluring blue eyes that betrays his true intentions. It’s something deeper and more thoughtful that was built up over years of witnessing the swell of savagery. If the eyes are truly the windows to the soul, the audience is given a glimpse into a meaningfulness that only sparks their own debates about their own toll paid to the dark nature of things.

Material Veracity

In a time where many heroes were relegated to capes and colorful western wear, it was Bullitt’s wardrobe that stood out. Simple, yet unrelenting in its style, there’s a reason why the looks are iconic. In an obvious nod to the previously set notions of how audiences distinguish their heroes, not a shade of white to be found. Instead, the audience is met with muted shades of black and blue. Only the standard trench coat betrays his place in the hierarchy of 1960s San Francisco and the world of crime fighting. Choosing to dress both the heroes and villains in many of the same pieces is not only realism at work, it’s also a defining nod to how blurred the lines can become when the timeless debate of good versus evil is at play. More than wardrobe, these pieces define the very real details of our perceptions. The clothes may tell a story, but finding the truth of the person who wears them is an entirely different proposition.

Man, Woman, And Machine

There’s no mistaking how intertwined society is with its automobiles. The film almost revels in its character connections to cars, especially when the anti-hero’s credentials are on the line. Bullitt himself is intricately linked with the mythos of the Mustang he uses in some of this film’s most well-known moments. The car is a roaring thunder of V8 power that is as intimidating and understated as the man behind the wheel. Its earth tone green could easily blend into the background, but takes over the dynamic of its scenes. There’s an irony to the fact that this anti-hero’s perfect machine is an American icon that is as closely associated with traditional beliefs as the most fairytale perceptions. The car and driver dynamic hits its crescendo in the unforgettable chase sequence that blatantly uses vehicles as characters. A sleek black Charger adds the powerful counterpoint that is more than capable of representing its villainous operators. As the chase winds its way through the twisting Northern California landscape, these two mechanical paragons do all of the talking for their respective drivers. The push and pull of every tense moment relays more than a standard foot chase could offer an audience.

When it finally concludes, the burning remains of a once-mighty vehicle promises to consume the very people who relied on its dominance. Unlike many films, Bullitt also assigns an influential vehicle to its leading female character. The Porsche 356 Cabriolet was just as at home on the race track as it was a city street. Its unique frame signaled to everyone this was a Porsche through and through. The choice of yellow may seem like a touch of femininity, but the choice gives Cathy another way to make her mark in a male-dominated society by undermining the traditional male aesthetic. If the anti-hero hero truly holds up a reflection to an audience’s flaws, then it only stands to reason that they must also face that reckoning. Bullitt’s final glimpses in the mirror stand as a reflection not only on himself but a society that was rapidly staring back at unrecognizable images. The decisions he makes unrevealed, the future uncertain. In the end, it’s the ultimate act of both a character facing their circumstances and an audience forever hesitant of their own.