Camera angles contain visual implications. They can connect, empower, or disorient. They can add ethereal yet tangible elements to a moment like menace or vulnerability, things that can be felt but not readily expressed through simple visuals. And using angles effectively can enhance a film remarkably.

In 1982, Sidney Lumet directed The Verdict, an adaptation of Barry Reed’s novel of the same name. Around 1997, Francis Ford Coppola put The Rainmaker onto film, joining that decade’s plethora of movies born from John Grisham books. While The Verdict earned five Academy Award nominations, The Rainmaker would barely recoup its budget despite nominations for three Blockbuster Entertainment Awards.

In The Verdict, Paul Newman plays an alkie ambulance chaser who takes a case suing for medical malpractice. Over in The Rainmaker, Matt Damon plays a fellow fresh out of law school who goes to work for ambulance chasers and ends up suing an insurance provider. Both lawyers expect their cases to be immediately settled, easy money, yet both become heavily invested in matters. Fueled by moral indignation, they enter their own respective David and Goliath legal battles.

Although several movies feature similar plots — A Civil Action (1995), Class Action (1991), Erin Brockovich (2000), Dark Waters (2019), and Philadelphia (1993) — they don’t always have the exact same scenes. On paper, The Verdict and The Rainmaker are often the same movie. Granted, legal dramas are one of the few film types which can be forgiven for being formulaic. Such stories can only be told within certain parameters. Every country and historical period has rules for courtroom conduct, and into such templates all legal dramas must fit. Even when fiction stretches things to accommodate drama, reality still restricts to some degree. However, The Verdict and The Rainmaker have two plot points that are particularly synonymous with each other.

Spoilers ahead.

Both films feature a quiet conference with a corrupt judge trying to push the good guys into a settlement as well as the surprise return of a reluctant witness. Granted, surprise witnesses with case breaking testimony are essentially a trope. To quote the Kentucky Fried Movie (1977), “As everyone expected, a surprise witness.” However, the characters in these films are basically cut and paste.

In The Verdict, it’s a nurse named Kaitlin Costello Price played by Lindsay Crouse. The Rainmaker features Virginia Madsen as Jackie Lemanczyk, an employee of the villainous insurance company with vital info about their bad faith practices. Both are trembling ladies troubled by their complicity in a morally indefensible situation, compelled by conscience to finally testify.

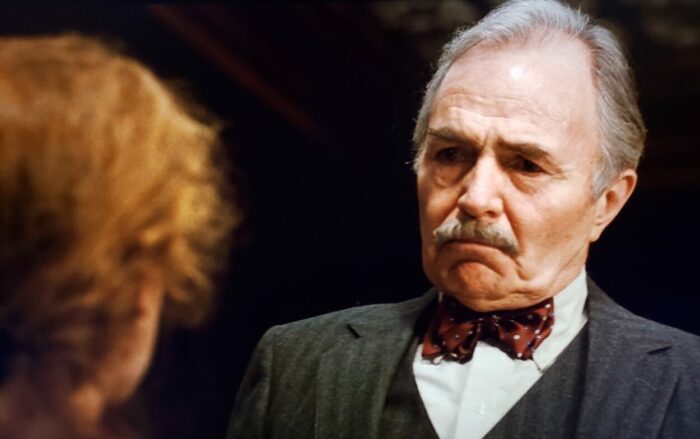

When Kaitlin Costello Price is called as a witness Lumet employs low angle shots on several occasions to different effect. When Paul Newman questions the nurse it gives him a heroic quality, but also allows for other cinematic tricks. As his character paces away from the witness stand, the camera follows him with minimal need for motion. This implies the sight line of nurse Price as well as the jury, showing Newman leading everyone to pay attention to the stony-faced doctor during the crushing rebuttal of his testimony. However, moments later, when James Mason cross examines nurse Price, that same low angle produces a menacing impression.

He’s literally looking down on her. Yet, he speaks softly until the moment he thinks her testimony reveals a chance to strike. His performance intensifies in condemnation, verbally beating her on the stand. All the while, the angle puts the audience in Price’s position, looking up as this man hammers down.

Any other primary shots feature the whole courtroom. The gallery of citizens and reporters (including an uncredited Tobin Bell and Bruce Willis) silently observing, and the jury quietly taking everything in. There’s never much shocked murmuring or agitation. Rather, everyone except for the most invested parties — Newman, his clients, and James Mason — seem disturbingly lifeless. Their disconnect from events made plain by their observable lack of reaction.

When a similar scene unfolds in The Rainmaker, Coppola chooses to show most of Jackie Lemanczyk’s entrance from the rear of the courtroom. Her initial entry involves zooming in on her, drawing audience attention away from anyone else. All this removes the visible reaction of anyone there save for the legal team protecting the insurance company. Their reaction is so obviously panicky it almost seems comical, whereas The Verdict shows James Mason and his subordinates remaining calmly collected in appearance despite immediately reacting to the surprise arrival.

In The Rainmaker, shots pinball in this scene to feature the most famous faces. This results in several cuts jumping around the courtroom, bouncing back and forth between speakers, such as when Jon Voight grows volcanic in his effort to discredit Jackie’s testimony — Voight yelling, cut to tearful Virginia Madsen. Perhaps intended to create energetic exchanges, these quick cuts don’t really add anything to the scene, though they do lose something Lumet captured.

By not jump cutting constantly, James Mason’s cross-examination becomes this relentless onslaught as he looms over Lindsay Crouse in a prolonged take. Lumet captured a natural impression of proceedings where the weight of a pause could crush. When Paul Newman looks down at Lindsay Crouse, he’s staring over the brink of the abyss he’s about to fall into if this testimony fails. In The Rainmaker, the audience is constantly looking up to Matt Damon during his Hail Mary play until a second passes and now they’re looking up to Virginia Madsen for finally coming forward… or we’re at the rear of the courtroom again looking at the back of heads. Coppola composes energetic exchanges with visual implications of being in a constant underdog position at the sacrifice of realism — everything here is mostly shot at some degree of low angle.

Then, there’s the judge scenes. Both carry the same gist. The judges in either film are basically on the side of the crooked lawyers. Here again, The Verdict and The Rainmaker make interesting use of low angle shots.

Portrayed by Milo O’Shea and Dean Stockwell, the judges couldn’t be more dissimilar in demeanor. Serving the exact same plot function in their respective scenes, both come out from behind their desks to chat at lawyers Newman and Damon. Low angle shots are employed heavily implying the judges looking down on whom they’re addressing.

Dialogue makes it clear that, friendly tone notwithstanding, O’Shea has no respect for the disgraced Newman, while Stockwell is obviously talking down to someone he views as an inexperienced inferior. Interestingly enough, while low angle shots put the judges on high, Mason and Voight are viewed on sight lines level with Newman and Damon implying an equality that dialogue disagrees with.

From both a cinematic and narrative standpoint, the scenes play out very similarly. The judges unsubtly nudged for settlement. The only downside for The Rainmaker is following it up with dialogue explaining what just happened. The Verdict trusts the audience to make sense of its implications.

Though these scenes are essentially the same, their stylization makes them feel very different. Lumet crafted naturalistic moments while Coppola sacrificed realism for cinematic flare. Neither is necessarily better, but it shows how dramatically different the same scene can be. It’s all about the angles. Used effectively, they add a lot.