Step right up, folks, step right up! Here you can see the most astonishing aggregation of cinematic wonders from the one and only director of Dracula and more! Marvels and monstrosities, freaks and foes, double-crosses and derring-do, all here in one package, the grotesque and the alluring invite you to cast your eyes upon them!

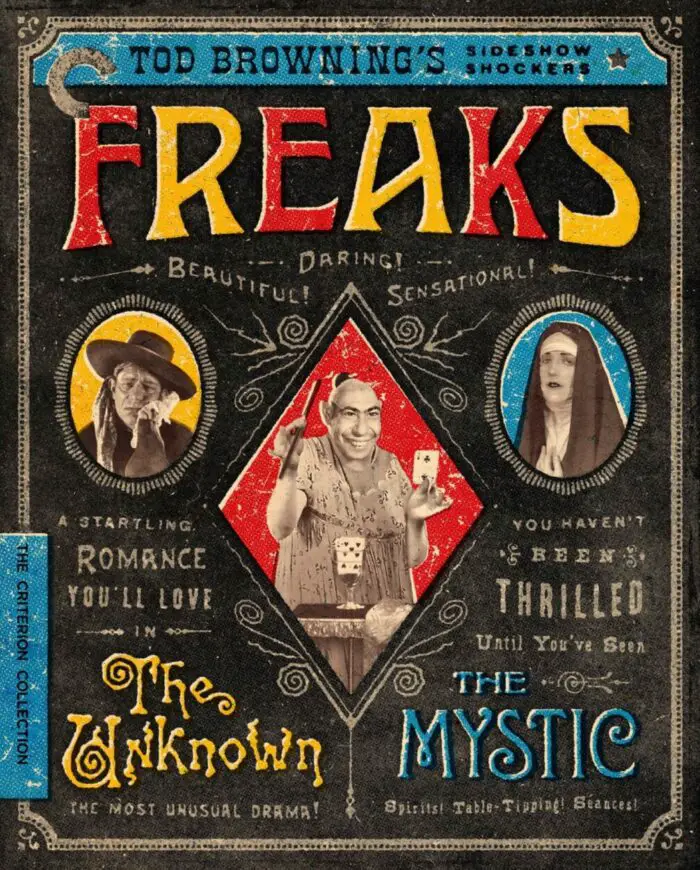

The Criterion Collection brings all the zeal of a carny barker with its two-disc Blu-ray/DVD Special Edition, spine No. 1194, Tod Browning’s Sideshow Shockers, collecting together three of the director’s full-length features from pre-Code Hollywood alongside a fairground’s full of bonus attractions.

The three feature films straddle the transition from the apex of the silent era to the start of the sound era, a time when Browning– who had run away from home as a child to the circus where he became a barker and contortionist– was among the busiest filmmakers in Hollywood. The most famous, or, perhaps, infamous of these is his 1932 Freaks, an early sound film that cast sideshow performers alongside “normals” in a curious quasi-horror film, exploiting audiences’ misguided belief that there is a permanent, qualitative difference between deformity and normality. Both 1925’s The Mystic, a rarely-seen slice of atmospheric exotica, and 1927’s better-known The Unknown, a star vehicle for Lon Chaney and Joan Crawford at the apex of the silent era, also take place in and around the circus sideshow, where Browning assembled a cast of freaks, outcasts, cons, villains, vagabonds, and lotharios tin the service of his edgy, morbid narratives. Together, these three films paint a portrait of a filmmaker perpetually fascinated by—and empathetic to—society’s outcasts.

The Mystic

The Mystic (1925) is the least known and, to be frank, the least compelling of the three feature films included here, but it’s nonetheless a rich piece of silent cinema featuring a striking performance from its star and an impressive visual design. Though it is typical of Browning’s fascination with oddity and criminality, its story is its weak link: a phony Hungarian psychic and a clever con man set off to America to swindle high society. Aileen Pringle stars as the faux psychic Zara in a series of exotic costumes created by the art-deco designer Erté (Romain de Tirtoff) and makes for a memorable diva. Conway Tearle makes less of an impact as her Svengali, Michael Nash. While the storyline stumbles, Browning nonetheless creates an eerie atmosphere of moral ambiguity and supernatural strangeness.

Even when Browning is at less than his best, his work still fascinates with its rich mise en scène that emphasizes, rather than dismisses, the supernatural. Never before available on home video, The Mystic is presented in a new 2K digital restoration from a 35mm safety grain in its original 1.33:1 aspect ratio with a new, modern score—one that is simultaneously anachronistic and atmospheric—by composer Dean Hurley.

The Unknown

If The Mystic is Sideshow Shockers‘ opening act, its headliner, were it not for the long and contentious history of Freaks, could well be 1927’s The Unknown. Here is a silent film that I can dare anyone to watch today and not find themselves absolutely in its thrall: such is the pull of its legendary stars, leading man Lon Chaney, “The Man of a Thousand Faces” with whom Browning collaborated on eight films, and a young Joan Crawford as the object of his character’s (and another’s, and the camera’s) affection.

The plot was too perverse for many reviewers and filmgoers, but The Unknown remains the most celebrated of the Browning-Chaney collaborations. Chaney plays Alonzo, a Spanish knife thrower who flings daggers with his feet. But he’s perpetuating a ruse, only pretending to be armless: his assistant, who wraps Alonzo’s arms in a tight corset each day, is his only confidant. Alonzo’s ruse keeps the law at bay: he’s committed crimes for which the law would certainly apprehend him if they learned he was sufficiently able-bodied to commit them, and a freak deformity (he has two thumbs on one hand) would identify him without any doubt.

Odd enough?

It just so happens that the object of Alonzo’s desperate affection, the beautiful and half-clothed ringmaster’s daughter Nanon (Crawford), has her own torment: she cannot bear to be touched by the hands of any man. Though the plot does not say as much, it’s implicit that Nanon has been prostituted out by her father and sexually traumatized as a consequence. Even the genial, gentle strongman Malabar (Norman Kerry) cannot so much as graze Nanon without her recoiling in horror. Nanon desperately desires love but cannot tolerate touch; Alonzo wants to love but cannot touch.

There you have already the Browning themes of psychosexual obsession, disfigurement, and deception. The plot accelerates wildly from there when Alonzo murders Nanon’s father; she witnesses his doing so, but can identify only his bifid thumb. To both make himself available to her and to absolve himself of the murder, Alonzo hatches a new plan: he will have both his arms amputated, truly becoming the man he has long pretended to be.

If you don’t know The Unknown, I’ll stop there and avoid divulging further spoilers of a nearly hundred-year-old film. There’s more in store for you in the wake of Alonzo’s symbolic castration, including a wild climax that brings his schemes to a fevered, nightmarish pitch. Throughout the film, the two stars are great: Chaney all tortured, pent-up grimace and lurid desire, Crawford ebullient and affectionate, her passions ready to explode. Watching Chaney perpetuate his ruse of armlessness is a delight unto itself: Browning had a real-life armless body double working with Chaney as his Alonzo flings knives, lights smokes, drinks wine, and plays guitar with his toes. For all its perversity, there’s a magic to The Unknown that cannot be denied.

The Unknown is presented in a new 2K digital reconstruction and restoration from two surviving nitrate prints by the George Eastman Museum, with a new (and less obviously anachronistic than The Mystic‘s) score, composed and performed by Philip Carli.

Freaks

I have always had a soft spot for Freaks, as transgressive a film as you’ll see from a major American studio in the censorious 1930s. Freaks is a film that stars and validates the non-normative in ways few films ever have. It’s a film I taught on multiple occasions, often alongside its less impactful source story “Spurs” by Tod Robbins, to students’ bewilderment, surprise, and awe. Essentially doing exactly what disability advocates ask for—and only infrequently see—today, Browning cast actors of various disabilities, or of different abilities if you prefer, in Freaks‘ traveling circus as entertainers shunned by mainstream society. Many of these actors were themselves real-life sideshow performers, a fact that revulsed, if unfairly, many viewers upon its initial release.

The “Freaks” of the film live by their own code, one that is both simple and radical: they accept their own, the fellow oppressed, with love and cheer. “One of us, of us, gooble-gobble, gooble-gobble, we accept her, we accept her, one of us, one of us!” they chant, an expression of performative embrace so defiant it struck a chord (one of three) some six decades later with the Ramones, who adopted it for “Gabba Gabba Hey (Pinhead).” Browning doesn’t hesitate to foreground the performers’ uniqueness, siding with them at the film’s terrifying conclusion, one that gives the “normal” trapeze artist, a beautiful icon of able-bodiedness whose singular disability is cruelty, a harsh if well-deserved comeuppance following a thrilling chase and fight sequence.

Freaks may have met with disdain and revulsion by most reviewers and audiences of its day, but it lives on as a remarkable work of pre-Code terror and the one film that let the sideshow performers themselves take, for a short time, center stage. Powerful and prescient, enlightening and terrifying, Freaks is a film that simply couldn’t be silenced.

The restoration of Freaks was created from a 35mm dupe negative and a 35mm safety print, both scanned in 5K resolution with its original monaural soundtrack restored. While some scenes suffer from a soft focus, the print is nearly grain free and as pristine as imaginable. The film is presented in its original 1.37:1 aspect ratio with optional subtitles for the deaf and hard of hearing.

Special Features

If Freaks, The Unknown, and The Mystic constitute the main events of Criterion’s three-ring circus, the special edition features no small amount of sideshows in the form of special features, most but not all of them supporting Freaks, in a package design that leans heavily into the circus aesthetic of the late 19th-early 20th century.

Audio commentaries by David J. Skal: Skal, author of The Monster Show, Hollywood Gothic, Something in the Blood, and Dark Carnival: The Secret World of Todd Browning, provides full-length, copiously detailed, and consistently informative commentaries on both Freaks (previously recorded for a 2004 Warner Bros. DVD special edition) and The Unknown. The Mystic receives a brief nine-minute introduction from Skal, focusing primarily on the costume designs created by Erté (Romain de Tirtoff), accompanied by images from the film and behind the scenes of its production.

Tod Browning’s Freaks: The Sideshow Cinema: An hourlong documentary from 2004 (also previously included on the WB DVD), narrated predominantly by Skal and featuring interviews with Todd Robbins (the American magician-lecturer-actor-author, not the like-named author of “Spurs”), focusing on Browning’s filmography and the representation of Freaks‘ sideshow performers. The documentary’s staged interviews and incessant music may be dated, but its content is nonetheless informative.

Reading of “Spurs“: The short story by Tod Robbins on which Freaks is based, performed again by Skal, prefaced by a brief contextual introduction. “Spurs” was originally published in 1923 and purchased by MGM as a potential vehicle for Lon Chaney before being reworked for the screen by Browning. Those unfamiliar with the story may be surprised to see how little of it finds its way into Freaks and how dark—darker even than the final retribution of Freaks—its conclusion reads.

“Prologue to Freaks“: A brief appendage to the film from 1947, a lecture-like preamble to the film added by its exhibitors as a type of disclaimer. At two-and-a-half minutes in length, its 700-odd words go by quickly, especially as Skal provides some context for the content in a simultaneous voiceover, but provide some insight as to how the film had been exhibited in the decades following its debut. Like the abovementioned documentary, Skal’s voiceover commentary, and the program of alternate endings, this prologue was also featured on the 2004 WB DVD special edition of Freaks.

“The Alternate Endings to Freaks“: A six-minute feature with Skal explaining the film’s alternate endings, including the unseen original with an apparently castrated Hercules singing falsetto; another of Hans professing his innocence; another of the same, shortened and made silent—all of these before the distributors settled on the extant version of the film’s concluding with Olga Baclanova’s sad squawking.

“Video Gallery”: Portraits from Freaks, a ten-minute parade of images of each performer—“freaks” and “normals” alike—in costume, including a rich set of some behind-the-scenes stills and promotional posters, set to period music by Paul Whiteman and His Orchestra.

“Ticklish Business Podcast”: A 52-minute episode from 2019 co-hosted by The Wrap’s Kristen Lopez and writer Samantha Ellis with guest independent producer Drea Clark, the three of them together exploring disability representation in Freaks. Freaks has long been one of the films disability advocates and critics have claimed as their own, albeit with some caveats, and Angelo Muredda notes this feature was added to the Criterion set only after complaints from the community (in particular from Film Freak Central editor and founder Bill Chambers, who tweeted that Freaks “is a key disability text, it’s ours”).

While Criterion has remained silent about the podcast episode’s late inclusion on the set, there’s no questioning its value, especially given that most commentary on the film, both here and at large, has originated outside the community of disability critics and advocates. Freaks is a problematic if inspiring text for many viewers and deserves a rich contextualization. The podcast is presented here in audio only, with only a single promotional image from the film onscreen for its duration. Here, I wonder if Criterion might have invited these three for a sit-down, à la the next feature with Megan Abbott, or included the perspective of any of a number of academics for whom disability studies is a scholarly specialty and Freaks an object of their attention.

“Sideshow Tod: An Interview with Megan Abbott”: Author, television producer, and critic Megan Abbott about director Tod Browning specifically and pre-Code horror generally, focusing on Browning’s deconstruction of traditional masculinities and his ability to decenter traditional paradigms by locating the “normal” at the periphery of his narratives while centering the other, especially in The Unknown and The Mystic. Alongside Skal’s commentary for The Unknown, his introduction to The Mystic, and his reading of “Spurs,” this 32-minute interview is newly commissioned for this Criterion special edition.

Wrapping up these features in a tidy digipak two-disc box is a 40-page three-color booklet insert with each film’s full cast, crew, production, and restoration details, anchored by Farran Smith Nehme’s essay “Todd Browning’s Ballyhoo Art,” a detailed account of Browning’s carny origins and Hollywood years, exploring the irony that Browning died just as interest in his art renewed.

While many of the features included on this Criterion special edition were previously available on Warner Bros. excellent 2004 DVD, the Collection has outdone itself once again: with one little-seen film, one silent-era classic, and Freaks in a stunningly clean new remaster, packaged with additional new special features alongside those previously extant, this collection of Tod Browning’s Sideshow Shockers makes for a rowdy, lively, challenging, and wholly satisfying day at the circus that was the director’s unique, unparalleled film art.