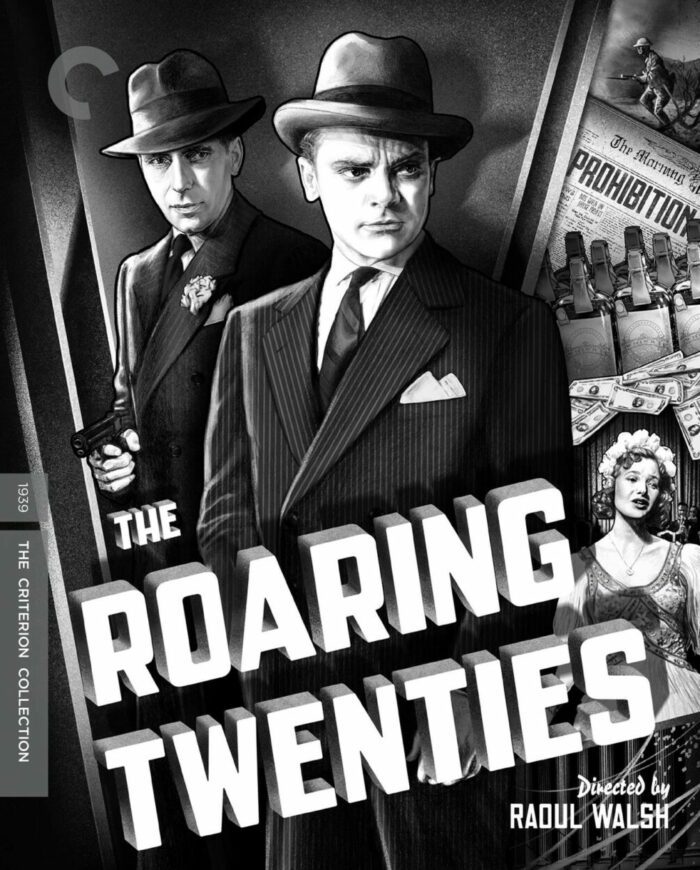

The Roaring Twenties is a crime film that seems on the surface like it ought be among the select greatest of its genre. After all, it’s adapted from a story by Mark Hellinger, whose syndicated column ran across the U.S. in the 1930s. It features the genre’s two greatest stars squaring off against each other in James Cagney and Humphrey Bogart. Its musical numbers: two of the cinema’s best-known, most charming songs of the era: “Melancholy Baby” and “I’m Just Wild about Harry.” And its ambitious scope takes a long view of the rise and fall of bootlegging gangsterdom from the end of World War I through its titular decade, The Roaring Twenties, up and well into The Great Depression that ended it. Veteran director Raoul Walsh, who would later direct High Sierra and White Heat, helms for Warner Bros., literally and figuratively the genre’s home.

And yet, there’s always been something just a little “off” with this film to my thinking. Perhaps its scope exceeds its bounds. The film clocks in at well under two hours yet often feels lethargic. Beginning as it does with the two leads’ meet-tough in the trenches of the Great War’s western front, where its narrative sows the seeds of disaffection that will grow into a vast criminal empire in the decade to come, Cagney and Bogart’s characters interact, briefly, as soldiers during the war, then not again for more than an hour (or in real time, nearly a decade), before locking horns as former friends turned uneasy allies and, finally, fierce rivals.

When Cagney’s Eddie Bartlett and Bogart’s George Hally share the screen, sparks fly and The Roaring Twenties soars. The two actors were at very different moments in their respective careers in 1939. Cagney was the undisputed king of the crime film, ruling the decade from his blistering performance in 1931’s Public Enemy up through his Academy Award-nominated turn in 1938’s Angels with Dirty Faces. In between, more than a dozen crime films in the decade’s hottest genre, made possible by the turn to talkies (and direct sound featuring rapid-fire dialogue, tommy-gun street shootouts, and screeching tires) and the public’s fascination with criminality during the Depression.

Bogart, meanwhile, wasn’t quite yet the Bogart the world would come to love and loathe in the 1940s and ’50s. In films like 1937’s Stand-In he hadn’t yet perfected the tough-guy persona that made him the industry’s biggest star with turns like those in The Maltese Falcon, Casablanca, or scores of films noir to come. In The Stand-In he played a light-in-the-loafers romantic lead with a penchant for a quick comic quip; he was an actor still looking for the tough-guy muse he would begin to find with his role in The Roaring Twenties.

It might not have been possible to foresee in 1939 that Bogart would in fact soon become cinema’s most bankable, recognizable, reliable star. He was third-billed in The Roaring Twenties, following Cagney and Jean Sherman, whose character sings the film’s hits. In retrospect, it’s hard not to wish for more of him in The Roaring Twenties, but Cagney is the star here, and it’s his character, the G.I.-turned-rumrunner who returns from war to find an uncaring public having turned their collective back on those who fought for their country.

The film’s ambition is to trace the DNA of the 1920s crime wave back through to the Great War that preceded it and the nation’s embrace of prohibition. It’s a theory espoused in Hallinger’s story and the film’s collaborative screenplay (credited to Jerry Wald, Richard Macaulay, and Robert Rossen). So much of the film’s “real” action—the methods by which Cagney’s Eddie Bartlett comes to power—is presented in faux-newsreel montage sequences with omniscient voice-over narration from John Deering explaining what happened rather than showing it. Though technically proficient, these are the very kind of expository sequences that Orson Welles would parody so viciously and precisely in Citizen Kane just two years on. Here, these seem like a storytelling dodge, skipping past all the good stuff to get to a dull sappy dialogue between Cagney and Sherman while Bogart languishes on the sidelines like a rookie waiting for his chance at the starting lineup.

Cagney, at least, can carry a film all on his lonesome anyway, and his character is a complex sort, more three-dimensional than the villains in most of the decade’s crime films. Cheated out of his chance at prosperity by his time in the service, he learns the ropes and builds an empire quickly, learning to leverage his growing position to crowd competitors out and keep the profits raking in. Yet for all his business skill and bravado, he’s lacking the emotional intelligence to understand others who don’t think like he does—especially women—and that proves his downfall. His Eddie, from idealistic recruit to crime lord to fallen wastrel, is a character worth caring for, and his eventual demise is one of cinema’s most iconic and deservingly imitated scenes.

The film’s cinematography, courtesy Ernest Haller in the house style for which Warner Bros. became known, contrasts ink-black dark with bright white and every shade in between, a rich chiaroscuro of striking black-and-white beauty. The makeup and design are first-rate, especially in the film’s final act when the long-teetotaling Eddie succumbs to drink and descends into despair. Martin Scorsese, who has made a few pretty good crime movies himself, cited the film as an inspiration, having seen its depiction of the mythology of the underworld’s cinematography on television in his youth. The remastering done here—created from the original 35mm negative—is spectacular, scanned and restored in a fine-grain 4K restoration that displays Haller’s cinematography and the stunning set design with accuracy. Kudos to Criterion for such a delightful restoration.

That said, the Blu-ray version included here looks nearly the equal of the 4K disc, which lists for a swank $49.95 ($39.96 sale on Criterion’s site as of this writing). Those more frugal-minded consumers might be every bit as pleased with the slightly cheaper Blu-ray version ($39.95 list, $31.96 sale) or even the DVD ($29.95 list, $23.96 sale). A 4K restoration of The Roaring Twenties is a premium purchase at a premium price, and while the film has its charms and its strengths, it’s not a crime film of the highest rank, lacking the incendiary performances, gripping narrative, and thematic insight of the genre’s best films.

Special Features

For this special edition, Criterion presents several special features, one of them new to The Roaring Twenties. Given the steep price of admission, the content, I am sad to say, underwhelms.

Audio commentary with film historian Lincoln Hurst. Hurst—who is a dead vocal ringer for TCM personality Robert Osborne—was a professor of history and theology who developed an affection for crime films, having contributed to disc featurettes for The Maltese Falcon, Angels with Dirty Faces, White Heat, and The Roaring Twenties. This commentary is from 2005, recorded originally for the Warner Bros. home video DVD “Signature Collection” release. Sadly, it’s a slog. For ten minutes there are no insights other than what is patently visible onscreen, and throughout Hurst’s halting observations only occasionally transcend the blindingly obvious. A few choice notes about the actors and production could have been distilled into a ten-minute visual essay on the film. Here’s one place Criterion needs to pony up: at $49.95 MSRP for a new 4K disc, purchasers deserve some new content. I’m sure there are any number of astute film studies scholars with a background in crime film who would do a great job with the task.

New interview with critic Gary Giddins. Giddins, primarily a jazz critic and historian whose work intersects with film (e.g. in his two-volume biography of Bing Crosby), accomplishes more in this 22-minute featurette than does the entire audio commentary from Hurst. The segment is more of a lavishly illustrated visual essay accompanied by voice-over than an “interview” per se; there’s little sense of the informality or give-and-take of an interview’s more dialogic nature. Nonetheless, the featurette is, aside from the remastering and repackaging, the sole new content created for this disc, and it’s a lively, insightful, and penetrating examination of The Roaring Twenties‘ context, crew, and cast. Giddins makes for an affable, knowledgeable host and the content is supplemented with a lovely variety of clips (those from The Roaring Twenties, all remastered) and images. Note to Criterion: more of this, please.

Excerpt from a 1973 interview with director Raoul Walsh. This excerpt comes from critic Richard Shickel’s series The Men Who Made the Movies and focuses on Walsh’s collaboration with Cagney on The Roaring Twenties. As such, it’s of poor audio and (especially) video quality, though the content, based on an interview with Walsh, who still, with his eye patch and silver mane, cut a striking figure in his mid-eighties. Sadly, it’s just four minutes long, a brief snippet of Shickel’s full episode (which you can still find on YouTube). I wonder if Criterion’s producers consider their patrons too impatient to sit through a full episode on a film’s director when only of a little of it addresses the specific film in question? A second note to Criterion: we are not.

“The Roaring Twenties: Into the Past,” a newly commissioned essay by film critic Mark Aschess. In contrast to Hurst’s leaden commentary track, Aschess provides a thorough and precise account of the contexts informing The Roaring Twenties. Asch, author of the New York Movies volume of the Close-Ups series of film books and a contributor to Film Comment, Sight and Sound, Reverse Shot, Filmmaker, Screen Slate, and other publications, provides a lively, carefully contextualized study of the film’s uneasy situatedness between eras.

Presented in a double-disc, single-fold jewel case, the set features one 4K UHD disc of the film presented in Dolby Vision HDR and a second with the Blu-ray version of the film and its special features. (The audio commentary is available on both discs.) The disc set also includes a trailer for the film, a pretty cool three-minute talk-to from writer Mark Hellinger, and English subtitles for the deaf and hard of hearing. Criterion does not provide subtitles for either the supplements or the audio commentary, however, a practice some other companies (shout-out to Film Masters) now manage regularly. The Asch essay is presented in a slight ten-page foldout sans illustrations or graphics.

The best news about The Roaring Twenties is that you get two of film’s greatest stars—Cagney and Bogart—near the peak of their powers as their careers intersected, and in a sparkling new 4K remaster that gives the film new life with its impeccable shadow and detail. It’s a film worth watching and knowing, even if its reputation exceeds its excellence. The worse news is, simply, the price. The Roaring Twenties is a fine film, though not one that is necessarily indispensable to a cinephile; at $49.95 MSRP and only a single new featurette to complement it, fans of the Collection are sure to be looking to one of the company’s Flash Sales or Barnes and Noble’s biannual 50% sales if they want to add this pricey bauble to their burgeoning collection.