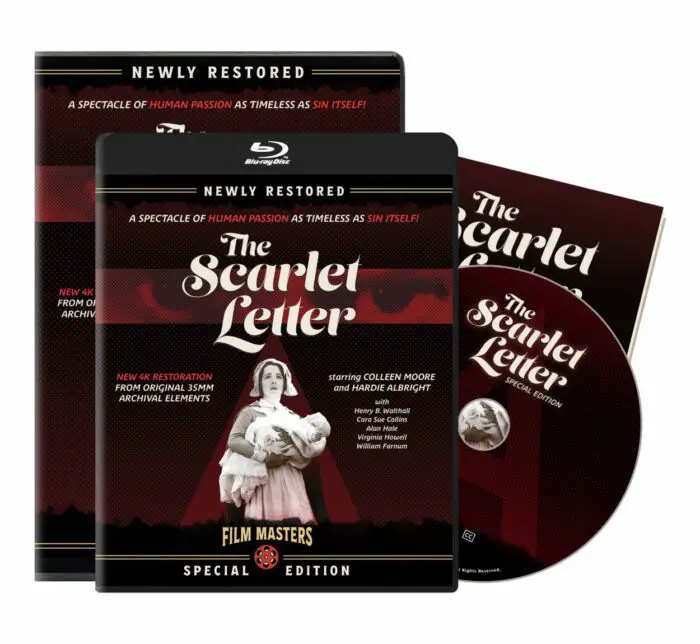

Film Masters, the film restoration and preservation consortium that began producing physical media earlier this year, brings its newest re-release to Blu-ray and DVD in the form of the first sound version of The Scarlet Letter from 1934. With a new 4K scan, this version of the (in)famous Nathaniel Hawthorne novel looks and sounds as pristine as any film from the era can. Starring silent-era star Colleen Moore in her very last film appearance, this version is neither the best adaptation of Hawthorne’s novel, nor is it the worst. It’s neither the most faithful to its source nor the most radical in its adaptation. Yet with this disc and its supplements, Film Masters makes the case for this 1934 iteration as an instructive case study in literary adaptation, in the transition from the silent era to sound, and in the tensions between art and commerce that have always dictated Hollywood’s output.

The Film

In its broadest strokes (and only in its broadest strokes), this version follows the outline of Hawthorne’s novel. Hester Prynne (Moore) is a widowed mother in Salem, Massachusetts whose young child, Pearl (Cora Sue Collins), is assumed to be illegitimate. Bearing a child out of wedlock was deemed a punishable offense by her Puritan elders, who consign her to wear the scarlet letter

“A” on her garments as penance for her sin. Hester would gladly accept her punishment and raise precocious little Pearl even facing the scorn of her peers, but her presumed-dead husband returns, adopting a new identity as Roger Chillingworth (Henry B. Walthall) and determined to identify the child’s father. A polite young reverend, Arthur Dimmesdale (Hardie Albright), struggles with the weight of his secret parentage, the pressure of Chillingworth’s inquiry, and his love for Hester—until his body and mind can no longer bear the weight of those pressures, revealing all to the shocked community.

That brief summary—sans subplots, contexts, themes, and Hawthorne’s unique style—follows that of the novel, even if it does it scant justice. Adapting Hawthorne to the screen seems like it’s proved as much a challenge as teaching his work to recalcitrant high schoolers. Even if his highly charged Romantic subjects, dark themes, and the complex relationship to the Puritan-era America he often examined made him a surprising bestseller in the 19th century, most filmmakers in the 20th century struggled when adapting his work to screen. Hawthorne’s richly allusive, figurative language and his thematic ambiguity practically sing on the printed page but can’t translate to the screen, which demands directness and clarity. But, especially in the first part of the 20th century as cinema gained near-immediate popularity and filmmakers needed narratives for their product, literary works proved common sources for film scripts—Hawthorne’s 1850 best-seller The Scarlet Letter among them.

On the surface, the novel seems like a reasonably promising candidate for adaptation. It’s not excessively long. The plot focuses on four main characters, each of whom is compelling and richly draw. It offers several confrontation scenes with dramatic conflict and requires little in production budget beyond simple costuming. The narrative structure is fairly straightforward, without (aside from Hawthorne’s prologue “The Custom-House,” which serves an important purpose in contextualizing the novel) narrative experimentation, and its themes have remained relevant since its publication.

Like many adaptations, this 1934 version hews close enough to the basic narrative events of the book. That, though, does not make it a particularly faithful adaptation, nor does it make it a particularly good one. The period from 1930 to 1934 was known as the Pre-Code era, that when Hollywood films, not yet fully subject to the strict dictates of the Hays Code (The Motion Picture Production Code), often took liberties with the sexual, moral, and thematic content of their films, chafing against attempts at censorship and often shocking their viewers. (Here’s one example.) With the economic austerity of The Great Depression fostering a new moral severity, the low-rent Poverty Row studios could barely risk much of a challenge to the Code. This Majestic Pictures release kowtowed to the Code, which initially condemned the film and only relented, allowing its public release, later on.

Film Masters’ restoration efforts here are impressive. The film has been in the public domain for some time, with poor-quality MP4 files all about the Internet. So too are its largely terrible reviews, both those from 1934, from a 1965 re-release, and anytime between or since. Yet, watching it in its brilliant 4K restoration provides some fresh light on the film. Moore is quite good in the role, even if she by 1934 was planning her escape from the industry. She never cottoned to the intricacies of sound production. As Chillingworth, Walthall, reprising his role from the excellent 1926 silent version directed by Victor Sjöström and starring Lillian Gish, makes for a threatening villain, even if his character retains none of Hawthorne’s three-dimensionality. The sets (also borrowed from Sjöström’s feature) are excellent, as is the cinematography in its final scene, and the film indeed offers a convincing depiction, if not a rebuke, of Puritan moralism.

Restoration aside, though, all of the film’s flaws remain apparent, beginning with its opening précis, which offers a decidedly un-Hawthornesque defense of Puritan corporal punishment and ideology. Moore’s Prynne is something of a Mary Sue in comparison to Gish’s flapper-esque wild child. So too is little Pearl, for that matter, just a put-upon young thing. As Dimmesdale, Albright is little more than a pretty face. A surprising chunk of screen time is given over to a godawful subplot invented for the screen featuring Alan Hale and some shenanigans with a courting trumpet. The film’s ending simply can’t accommodate the intentional ambiguity of Hawthorne. Did Dimmesdale bear the stigmata of the letter “A” himself? This film makes it so.

The Gish-Sjöström collaboration may well be the best adaptation of The Scarlet Letter even to date. It’s not the most faithful, but it is highly romantic and evocative, a conjoining of two of the silent era’s greatest talents. The 1995 Roland Joffé-Demi Moore-Gary Oldman film is not only unambiguously the worst of all Scarlet Letter adaptations; it bears the mark of its reputation as one of the worst films of all time of any kind. (It’s a reputation not unearned.) The most faithful is probably PBS’s four-hour 1979 miniseries starring Meg Foster; the most inventive, if you are willing to count it, is certainly 2013’s Easy A starring Emma Stone as a virginal high schooler who embraces Hawthorne and embarks upon her own crusade to self-identify as her school’s most notorious tramp.

This version of The Scarlet Letter might not approach the excellence or notoriety of these others, but it’s nonetheless an interesting episode in cinematic history and in that of adapting Hawthorne to film, one Film Masters makes all the more appealing by virtue of its excellent remastering and contextual features. The film was recently scanned in 4k from the 35mm preservation print made from the original camera negative, restored by Janice Allen at Cinema Arts in conjunction with UCLA Library Film & Television Archives, in its original theatrical aspect ratio of 1:33:1 on region-free disks and includes English SDH with DTS-HD and Dolby AC3s audio options.

Special Features

Film Masters provides helpful context for this release with several special features focusing on the film’s production and reception, its star Colleen Moore, its adaptation of the Hawthorne novel, and its 1965 re-release.

Audio Commentary: This track alone is worth the entry price. Professor and author Jason A. Ney of Colorado Christian University, who also provides commentary on Film Masters’ The Killer Shrews, delivers a wide-ranging yet expertly focused track. Among the topics are Hawthorne’s novel (Ney is a professor of American literature), Moore’s career, as well as those of Walthall and even Iron Eyes Cody, the Italian-descended actor famous for his native American roles and single glycerin tear in the “Keep America Beautiful” campaign, who appears briefly in the film, the film’s Puritan contexts, including their appetite for public punishment, the incoming Hays Code and the challenges faced by Poverty Row studios like Majestic Pictures, and the importance of film restoration, even for “less-than-stellar” efforts like this one and more.

Cora Sue Collins, now 96, who plays young Pearl in the film, joins Ney for the latter half of the commentary. Collins was a child actress in great demand during the ‘30s, appearing in 47 films before retiring from the industry at age 18. Her joy at being able to see the preserved version of the film is palpable. And while the disc’s other special features do little more than fill in some gaps, overall, the commentary track is simply excellent.

A Sin of Passion: Hawthorne in Film: This ten-minute featurette is based on a new single-camera interview with author Justin Humphreys and discusses the long and uneven tradition of adapting one of America’s most singular authors to screen, from the inception of cinema to Easy A, including adaptations of works other than The Scarlet Letter.

Revealing The Scarlet Letter: This ten-minute featurette is based on a new audio interview with producer Sam Sherman of Salem, Massachusetts, who acquired the rights to the 1934 film for its 1965 theatrical re-release and who collaborated with Film Masters on the restoration and special features here. While Sherman’s work to re-release the film in theaters may well have been a pivotal moment in his own career, it’s harder to make the case that his doing so had any particular relevance to the film, its reputation, or this re-release, aside from his owning the master.

Salem and the Scarlet Letter: This ten-minute featurette provides some archival footage provided by Sherman accompanied by audio narration by John Carradine. The content provides some insight for viewers who might know little of Hawthorne’s life or heritage. His mother was, like Hester Prynne, consigned to raising her children in the absence of a father, and his great-great-grandfather John Hathorne was one of the three judges in the Salem Witch Trials who sentenced numerous innocents to their death for alleged practice of witchcraft, though these biographical facts go unmentioned. The poor video—stabby zooms and shaky-cam, never really meant to be presented in a professional format—make it difficult to watch.

A Doll’s House—Silent Stardom, the Sound Age, and Second Acts: This excellent illustrated essay on the pre- and post-career of Scarlet Letter star Colleen Moore comprises the entirety of the disc’s 16-page four-color booklet insert. Moore was as famous as any star (save Gish) of the silent era and by the time she made this film in 1934 found herself disenchanted with the industry and eager instead to take her new act—a $500,000 doll house—on the road (it has resided at Chicago’s Museum of Science and Industry since 1949). The essay, for all its strength, is nearly silent on her work in The Scarlet Letter: only a single sentence addresses the film. One gets the impression that’s as Moore would have it.

The disc is presented in a black jewel case, in contrast to Film Masters’ prior Blu-ray releases, which arrive in the standard blue cases. Given that black cases normally accompany UHD 4K releases, some might assume that The Scarlet Letter is pressed on a UHD disc. It’s not: it’s a 4K remaster on a standard Blu-ray disc.

The Scarlet Letter (1934) Special Edition is available on Blu-ray and DVD (MSRP: $24.95 and $19.95, respectively) from retailers Nov. 21, 2023.