Restaurants have opened for indoor dining in major cities, hospitalization rates have plummeted across the United States, and the European Union has discussed opening its borders to American tourists. We may not get another summer on our couches, sweating in strappy tank tops, our iPhones pressed to our faces as we talk to friends and relatives from the safety of our rooms. With the possibility of a post-COVID summer upon us, we’re looking towards returning to bars and concerts and spending weekends with the people we’ve missed the most. We’re also coming off a year of trauma: watching a temporary hospital constructed in Central Park, finding the first 100,000 deaths printed on the front page of the New York Times, and feeling powerless as loved ones going into comas after contracting the disease. We’re stepping out of our homes, blinking into the spring light, almost unsure that it’s real, that the United States has emerged on the other side of this crisis. Where do we go from here?

There’s something to be learned from Eric Rohmer’s The Green Ray, which follows newly single (recently dumped) Delphine as she travels aimlessly around France in search of “a real vacation,” as she puts it. She had been expecting to visit Greece with a friend. When her friend bails and Delphine finds herself unexpectedly on her own for August (when Parisians typically flee the city heat for four weeks), she refuses to sulk in her apartment. From Paris to Cherbourg to La Plagne to Biarritz to St-Jean-de-Luz, she travels across France, creating dramatic tension in the film’s relentless space. Her possibilities are endless—just like us, newly released from our homes, free to go just about anywhere. What do we do with all this choice? Do we even want it? Delphine, at least, perceives this choice as an internal void.

Delphine cries often. She cries on a stoop during lunch after an acquaintance interrogates her about why she refuses to meet someone new. Delphine insists that she’s not sad or isolated, that her friends don’t understand her, but her awkward way of stumbling through her defense implies that she wishes she could indulge in superficial conversations with strangers. Single women are often expected to partake in flirtatious games to meet a man, but Delphine has no idea how to, as she says, “hide her hand.” Instead, she has an anxious desire to engage only in meaningful interactions. She has no time for superficiality, even in the long but vapid days of summer.

The Paradox of the Beach

Delphine arrives in Biarritz for a beach vacation. Typically a space of mass culture and leisure activities, such as sunbathing and volleyball and wearing strappy bathing suits, directors usually represent the beach as an embodiment of blissful summer, spontaneity, and youth (think of comparable French films such as Un Acte d’Amour or Pierrot le Fou). The Green Ray instead explores the paradox of the beach, turning it into a site of isolation and loneliness. The opening high-angle shot over the coastline emphasizes the throng of swimmers and sunbathers, all oblivious to Delphine’s internal struggle. As she wades in the water, beachgoers crowd the image. Then Delphine lies bored and restless on her towel, listlessly running her fingers through the sand. She is picked out by the camera and shown in contrast to strangers happily building sandcastles or chatting with their entourage. Everyone has left behind the stifling heat of the city, seeking paradise in the promise of solitude. It’s as though she hasn’t left Paris or the city has come with her. Her dislocation becomes intensified, as now Delphine experiences dissatisfaction in a place of leisure, a place she should be happy.

Could this be our summer? Wandering without purpose? Seeking a thrill to contrast the loneliness COVID brought on? We’re now used to a different way of life, much slower and infinitely more solitary. There will almost certainly be a subset of people—a large one, most likely—that parties through the most extended, superficial season. And in the fall? If Rohmer has anything to teach us, it’s that the summer is a mode of waiting. It is an in-between of life’s defining moments, where change may not happen but its possibility is felt. But when summer is over, his films end (not just Le Rayon Vert, but also Le genou de Claire and La Collectionneuse). It’s as though Rohmer is uninterested in telling the end of a story, preferring to cut his films off before any climax in favor of exploring the quiet character revelations that lead up to those moments of change.

But in real life, time continues ever on, and it moves with relentless speed. As we trepidatiously return to our so-called “normal” lives, we’ll have to find a way to carry forward lessons from the past year—like being calm and organized in the face of change, determined but patient to find a new purpose for our day-to-day, and self-reliant but connected in our time alone. It’s possible that, like Delphine, with all the changes in our lives, we’ll find ourselves grappling with how to find purpose and connection in the summer months.

The Promise of The Green Ray

Walking to the beach, Delphine overhears a conversation about Jules Verne’s book The Green Ray. She overhears one of the strangers quote Verne: “He said when you see the green ray, you can read your own feelings, and those of others.” Another gives a scientific explanation of the green ray, describing the atmospheric conditions necessary for its appearance. He explains, in detail, how the beam occurs when the sun sets and its yellow rays curve in the atmosphere, creating a green line that appears just before the sun dips below the horizon. Delphine knows that this is what she has been seeking: a deeper understanding of herself and those around her. She stares at the sunset, willing it to reveal something to her. Newly released from quarantine, where introspection and self-interrogation became vital themes, we too may seek a deeper experience than is typical from the summer. What is it we must learn from the green ray? If we were to see it, what would the flash of green teach us after this year of isolation? Of course, the green ray is supposed to be the rarest in the summer, when the atmosphere is the haziest.

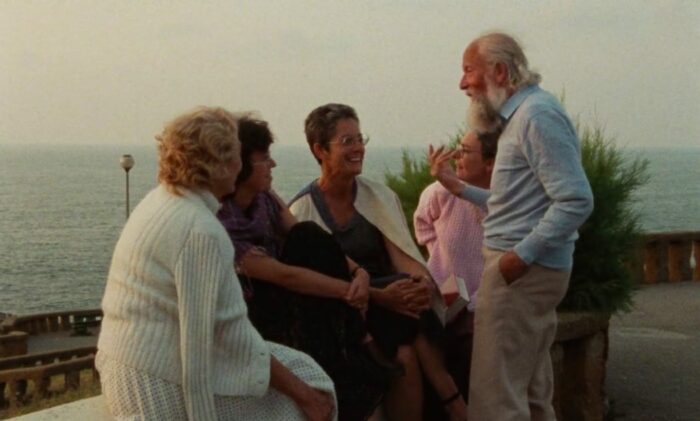

The beach at Biarritz allows Delphine a chance for ephemeral sociability and chance encounters. She meets a young Swedish woman and various men. There’s a great feeling of social mobility at the beach, where strangers can form weak and temporary ties before returning home. Everyone is here temporarily, for escape, creating a social receptivity not found in cities like Paris. Delphine tells her new friend that she hopes to meet her ideal man in the ocean—revealing that she still romanticizes the beach and the possibility to pick a stranger from the crowd and have a summer fling. Of course, despite the social possibility of the beach, this doesn’t happen. Delphine gets ready to return home to Paris.

At the Biarritz train station, she meets a young man. They bond over a shared appreciation of Dostoyevsky, and she makes the impulsive decision to go with him to Saint-Jean-de-Luz for a couple of days. Walking downtown in the evening, Delphine insists they follow the sun. She tells him about the green ray, quoting the conversation she overheard in Biarritz, and he asks what it means. She replies, “It helps you to know.” “Know what?” “I’ll tell you later.” She lets fate bring her to something significant: to determine whether this man is a suitable partner. To know if he is the answer to her search for something deeper than what the summer offers. On a cliff overlooking the water, Delphine cries once again as they watch the sunset.

The film’s final moments oscillate between an image of the setting sun and Delphine’s tear-streaked face. As the sun dips ever-lower into the sea, the green ray flashes, and Delphine’s despair is wiped from her face. She gasps and laughs. This is the last image. We do not know where she goes from here. We do see her moment of hope after finding that which was nearly unfindable: the green ray in the summer, and someone to devote herself to.

Desire and longing, crowds and loneliness—these are thoroughly modern themes that pervade this film. They are also themes that may come to define our summer. As we count down the days to June (a marker for borders opening, restrictions lifting, and life generally returning to normal), The Green Ray reminds us of the summer’s possibility to be a period of waiting, a season of futilely seeking the “perfect vacation,” and an opportunity for introspection in the year’s hottest, longest days. In The Green Ray, Rohmer turned the concept of summer on its head, making it not a season of superficiality but longing and seeking deeper truths. His vision might be what we’re in for.