If there is one single potential subject all filmmakers share in common, it might be cinema, itself. From Keaton and Chaplin to Wilder and Ray, Antonioni and Fellini to Tarantino and Chazelle, the process of filmmaking has been a topic too tender—or perhaps too painful!—for filmmakers to ignore. Fifty years ago this month at the 1973 Cannes Film Festival, the French Nouvelle Vague auteur François Truffaut debuted his La Nuit Américaine aka Day for Night, a behind-the-scenes film-about-film labor of love, to a warm reception, one suited to its sentimental affection for cinema, even if it would not be universally shared.

The Cannes program notes described Truffaut’s festival-opener as the director’s “long-awaited valentine to the cinema, a movie about the making of a movie and perhaps his most endearing work to date” and noted that “the emotional climate of Day for Night is as warm and sunny as the Riviera locations where it was shot.” Awards followed from critics groups, and The New York Times named it the Best Film of 1973. In the Los Angeles Times, Charles Champlin predicted it to win the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film: “His homage to the movies and all who make them is beyond question the warmest, liveliest, funniest, slyest, the most revealing and the most deeply affectionate ever paid, and I can hardly imagine a Hollywood heart remaining unmelted” (qtd. in Balio, The Foreign Film Renaissance on American Screens, 1946–1973 264). Champlin’s prediction came true.

The film’s warm tone and sentimental approach to cinema did not, however, sway Truffaut’s former friend and ally, Jean-Luc Godard, who attacked the film, its director, and everything in its wake. Day for Night, as I’ll continue to call it here, for all its apparent benign, bourgeoise innocence, essentially became the film that permanently fractured the New Wave and ended the decades-long friendship between the two directors. Fifty years on, it remains one of the most beloved, and perpetually fascinating, films-about-filmmaking in a subgenre that has seen its share of treacle and triumph. It’s a film that explores the boundaries and conflicts between reality and illusion from its first shot to its last, and it’s a love letter to the cinema that expresses its maker’s rapturous affection for the art form as or better than any of his early Nouvelle Vague triumphs.

Day for Night begins with clever sleight of hand, set in a busy Parisian square, as local denizens bustle about their daily business, exercising their dogs and patronizing the park vendors. A young man exits the subway. A car passes. An older man walks down some steps, where he encounters the younger man, who gives him a hearty slap across the cheek. Aside from the mannered action of the unconvincing slap, it seems a shot that could open any number of films, with its ground-level establishing perspective, craning action eventually singling out two antagonists, and culmination in an inciting event that, we are led to assume, will initiate the narrative. But it’s a fiction within a fiction, brought to a sudden halt by the close-up of Truffaut himself crying out “Cut!”

The car moved too quickly, a dog-walker too slowly, a bicyclist missed his mark, and the young man’s slap was convincingly unconvincing. It will all need to be redone, and as is the case so often on set, following some ad hoc slapping instruction, another take is soon underway: actors reset their marks, cameras prepare to roll, and the crew—gaffers, PAs, script girls, boom operators, cinematographers—resumes their work. With each new take, more of the shot is revealed as an artifice, a construction, one elaborately scripted, staged, lit, and performed, prone to folly and subject to the occasional mulligan. To Truffaut, though, the work is more than a mere exercise; it’s, as we’ll see, the art that haunts his dreams and gives his life purpose.

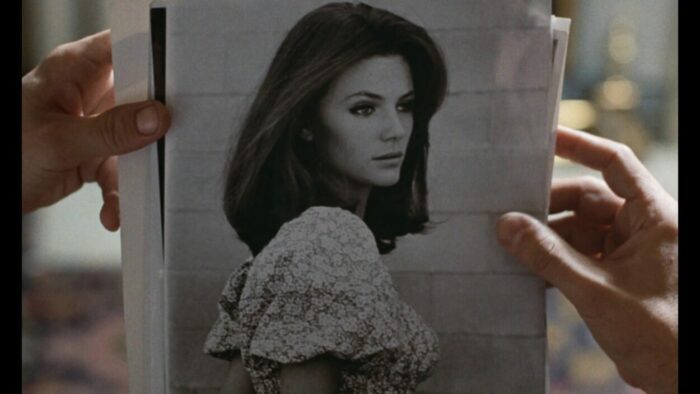

Truffaut, like the actors Jean-Pierre Leaud and Jean-Pierre Aumont, is playing a role here, that of this feature film’s director, Ferrand. Leaud plays Alphonse, the young male lead of this film-within-a-film we’ll soon learn is called Meet Pamela. Alphonse’s character is Pamela’s new husband, and Aumont plays Alexandre, husband of Alphonse’s character and rival for Pamela’s affection. It’s fascinating that Truffaut would choose such a mundane melodrama as the topic of what was obviously a film about which he cared deeply. Meet Pamela, all lurid potboiling will-she-or-won’t-she stuff written around its star (Pamela is played by the British Julie Baker who is played by actress-of-the-moment Jacqueline Bisset), seems like a far, far cry from the directness of Truffaut’s first films, those that heralded him as one the key voices of the Nouvelle Vague. But it’s one in which his character Ferrand, his alter-ego stand-in, remains deeply invested despite its melodrama.

If Godard was the radical intellect of the Nouvelle Vague, Truffaut was its emotional champion. His first films—The 400 Blows (Les Quatre Cents Coups, 1959), Shoot the Piano Player (Tirez sur le pianiste, 1961), and Jules & Jim (Jules et Jim, 1962)—were all highly regarded for their directness and naturalness. Only after these did his work suffer the kinds of critiques he’d made of others as a critic at Cahiers du cinéma. The Soft Skin (La peau douce, 1964)—of his films, the one that might most resemble the bourgeois melodrama of the fictional film-within-a-film “Meet Pamela”—met with less enthusiasm, as did his American adaptation of Fahrenheit 451 (1966). Godard, meanwhile, moved from Breathless (À bout de souffle, 1960) to Contempt (Le Mépris, 1963) to Pierrot Le Fou (1965), each more audacious and provocative than the last before 1968’s supremely nihilistic Weekend, a film that declared, apparently without irony, “The End of Cinema.” His 1972 Tout Va Bien railed against capitalism with an arch Brechtian experimentalism set in, get it, a sausage factory.

By 1973 the two men who led the revolution were no longer close, but it still surprises that it would be the seemingly benign Day for Night that would drive a permanent, final wedge between them. They had worked together (Truffaut gave Godard a job at Cahiers), collaborated together, even protested together at Cannes in 1968, even as their filmmaking took them in different directions. They were always opposites: Godard the arch, aloof, intellectual, cool-cat in shades decrying commerce and capitalism, Truffaut the more warm, open, slightly nerdy people-pleaser who conveyed his emotions with his art. But Godard had begun a phase of self-criticism that extended to critiques of all cinema around him, including the Nouvelle Vague and Truffaut’s films.

Day for Night was, for Godard, simply too much.

But for Truffaut, it was a life’s sole passion. As he wrote in Truffaut by Truffaut, he knew no passion, no joy, other than cinema:

I used to see everything in life as competing with the cinema. That is to say, I detested the theatre because it was in competition with the cinema, but for the same reason I didn’t go in for winter sports, I don’t know how to ski, I don’t know how to swim, I can’t do anything. I will not go to look at a race or a match or whatever it might be, because I would have the impression of cheating on the cinema. I would not even think of going hunting or fishing and such. I’ve changed my ideas with time, I’m tolerant, I accept the fact that other people go fishing or hunting or skiing, but I myself do not take part, no.

His obsession is fully on display in Day for Night, the single one of his films that explores cinema directly, if in the guise of a romantic farce. “Meet Pamela” seems little more than a clichéd melodrama: in fact, in many ways, with its star casting and elaborate production, it seems almost the kind of “quality” production a younger Truffaut once railed at in his Cahiers manifesto “Une Certaine Tendance du Cinéma Français” (“A Certain Trend of French Cinema”). The young ingenue is so irresistible even her new father-in-law can’t resist making a romantic overture, despite what his own son and wife might think.

In the film’s proper diegesis, so to speak, the actors portraying these characters have their own conflicts: Alexandre (Aumont) has aged out of the lead roles he used to enjoy, as has the former diva Séverine (Valentina Cortese), who can no longer remember her lines; the young lead Alphonse (Leaud) has fallen too hard for the fetching new script girl Lilianne (Dani); and Julie (Bissett), the ingenue, is recovering from what folks used to call a “nervous breakdown” and married, controversially, to her much-older doctor.

Ferrand (Truffaut) is busy trying to keep things together, racing feverishly to put out one fire after another. A supporting actress’s unannounced-but-visible pregnancy poses one problem. An omnipresent camera crew documenting the making of “Meet Pamela,” constantly underfoot, is another. (Alexandre and Alphonse, when interviewed separately, each charmingly assume the film is all about his own character’s quest.) The film’s producer is a constant reminder of the limitations of the budget and time. Retakes are costly and stunts risky, especially a car crash that requires the expertise of a stuntman, brought in for the day to double for Alexandre plummeting over a cliff.

Tensions on the set are further exacerbated when Alphonse is jilted by Liliane, who runs off with the film’s strapping stuntman. Alphonse responds by bedding Julie, but mistakes her pity for love, and in a pique, reveals the affair to her husband. Alexandre, meanwhile, is injured off-set in an auto accident and dies on the way to hospital, in a less spectacular event seemingly foretold by the movie stunt. If art imitates life, so too does life imitate art. The film will have to conclude without one of its leads.

Ferrand, though, is nothing if not competent. He’s long since given up hope that “Meet Pamela” will be any good and will now settle for a film that is finished. The egos and affairs of the cast and crew swirl about him, but he manages each of these crises with an apt solution. The script girls and assistants are treated with the same diplomatic courtesy as the picture’s stars. Ferrand is especially adept at coaching his actors through the finer points of their performances, an ability for which Truffaut was well known. The ending of “Meet Pamela” will be no different. The cast and crew, led by Ferrand, will grieve their fallen comrade then get back to the business of doctoring the script, deleting a scene, and reworking the ending to use a double.

Even though Ferrand seems to get the job done, the production still haunts his dreams. On three (apparent) consecutive nights, Ferrand, in exactly the same position in bed, finds remnants of the day’s conversations filtering through his mind, and his dreams take over the screen. A boy walks with a cane through a city, reaching a closed metal gate. Eventually, he uses his cane (like Ferrand’s omnipresent hearing-piece, a metonym for a disability, perhaps, or a limitation transcended) to hook the caster of a display and reach his goal: prized publicity photos of Citizen Kane, which, in the third dream, he pilfers before stealing away, “a thief in the night.” Ferrand/Truffaut has become, via this stand-in for himself, just about the same age of Antoine Doinel (Jean-Pierre Leaud) in The 400 Blows, closer to, one with, Orson Welles, one of the few filmmakers he took pains to laud in “Une Certaine Tendance,” and one with the cinema itself.

Ferrand, it seems, dreams of achieving a dream, of gaining access to the cinema of Welles and the other auteurs he adored as a youth. It’s a dream Truffaut himself had achieved, really, with his very first outing, The 400 Blows becoming nearly as seminal to cinema as Citizen Kane itself. The significance of the dream sequences seems almost perversely, inordinately out of scale in comparison to the mundane, by-the-numbers production of “Meet Pamela.” On the set, work continues, jerry-rigging solutions and assessing dailies, shot in loving montages of fetishized camera gear and film reels set to loving, frothy accompaniment by Georges Delerue.

After contemplating Alexandre’s death and the film’s fate, left to the whims of the insurers, Ferrand muses: “films will be shot in the streets, without stars or scripts.” It’s as if he is recalling the aims of the early Nouvelle Vague and films like his The 400 Blows and his compatriot’s Breathless. In fact, it’s almost impossible not to think of Jean-Paul Belmondo and Jean Seberg improvising with their director in the Parisian streets as Ferrand utters those words. Perhaps without knowing it, or perhaps with, Truffaut was anticipating the end of an era, if not the “Tradition of Quality” he’d rejected but the Nouvelle Vague he’d helped create.

Godard loathed Day for Night, and he did not wait long to tell Truffaut so. Among others, Bert Rebhandl cites this episode in Jean-Luc Godard: The Permanent Revolutionary (2023). Godard wrote his former friend and colleague the very next day to express his loathing. “Yesterday I saw La Nuit Américaine. Probably no one will call you a liar, so I will.” Godard continued the attack on several fronts. He accused Truffaut of using the money spent on stars and sets to seduce audiences to believe that filmmaking is beautiful and artistic, and then had the temerity to ask for money from Truffaut to fund his own projects, claiming that “while others in France were making “expensive movies (like you), the money that was reserved for me was swallowed up […] and I’m stuck.” He suggested entering “into coproduction with us for ten million.”

Flattery was not a tack Godard would employ in seeking funds. The insults did not achieve their aims. Nor did they stop with insults to the work. Godard insulted the woman who raised Truffaut and befriended them both. Godard also said he “wonders why the director is the only one who, in La Nuit Américaine, does not fuck.” (Truffaut was himself involved with Bisset during the production, a fact with which Godard was likely aware, and the attack stung: Truffaut confessed that a state of arousal was part of his muse.) Truffaut wrote a long letter back, rejecting his claims and his requests, telling Godard, “you’ve been acting like a shit.” He criticized Godard’s recent anti-commercial output and his working methods, especially the occasionally harsh treatment of cast and crew that Truffaut had taken pains to present so honorably in Day for Night.

Several more letters continued, and both Godard and Truffaut continued their filmmaking on their increasingly disparate paths. Godard for decades and right up to his recent death at the age of 91. Truffaut made another eight films in the decade following before he died, relatively young, from brain cancer at 52 in 1984. With Day for Night, the revolution in filmmaking Godard and Truffaut began as friends left the two as enemies and the movement largely concluded, although its impact continued worldwide. Fifty years, later, we still have the films, from The 400 Blows and Breathless to Tout Va Bien and Day for Night and everything in between. And Day for Night, a film that depicted filmmaking as its own loving and dedicated community, despite Godard’s scathing assessment, remains the singular film that encapsulates Francois Truffaut’s deep, profound passion for the cinema—by his own account the strongest passion the director ever felt.