If analyzing Robert Egger’s films often feels like trying to find meaning in a meaningless world, or if you’re unsure if you’re watching a masterpiece or a fever dream, you might just be on the right track.

In his 2019 psychological horror film The Lighthouse, Eggers tells the story of two lighthouse keepers confined on an island. We see the story unfold through the eyes of the younger “wickie”—the 18th-century term for lighthouse keepers, apparently—Ephraim Winslow (Robert Pattinson), who struggles with the demands and quirks of the older keeper, Thomas Wake (Willem Dafoe).

While psychological horror films are created with the intention of provoking the viewer to ask questions, The Lighthouse generally raised just the one: What the hell did I just see?

In order to start answering this, one must remember that all aspects of the film were specifically designed to harbor a sense of disorientation. This goes beyond soundtrack and editing; the fact that filming was on an aspect ratio of 1.19:1, (an almost square frame that was popular in the late 1920s) and in black and white was done intentionally. The filmmakers chose this specific format in order to achieve “a really confined, claustrophobic frame,” as stated by director of photography Jarin Blaschke. Another example is the placing of light, which in the opening scenes is set between the two characters but in subsequent scenes wavers between them as they descend into madness.

It is also important to emphasize that there is no correct way to analyze and hypothesize about meaning in The Lighthouse. Perhaps there really is no method in the madness, as Eggers himself has stated that he’s “more about questions than answers in this movie.”

That being said, I will do my best to guide you through The Lighthouse‘s ambiguity and allusions, as when one pays close attention, a trail of clues appear which in themselves can lead to all sorts of metaphorical deep dives.

To begin, the most common and straightforward take on the movie is that Ephraim simply went insane. Tortured by his past as an accomplice of death, his helplessness, anger towards his father, and Thomas Wake’s abuse finally broke his sanity. There are various takes on when exactly this happens, but the general consensus is that it culminates the night he falls from grace and finally gets drunk. Another hypothesis is that the “liquor” they drink is always kerosene, which poisons them and causes hallucinations. Whichever the case, from this point forward Ephraim descends into insanity, killing Thomas and himself in the process.

I believe this take holds truth in it, especially because this is a classic two-handler movie—a film in which two characters compete, usually with one character terrorizing and antagonizing the other until the second character finally explodes—yet we must remember that this is also an A24 production of a Robert Eggers horror film. If the company’s past productions are anything to go by, the metaphorical and contextual aspects of the film go much deeper than that.

Another much-talked-about aspect of the film is its variety of Jungian-related symbols and their direct effects on the plot. After all, in the words of Eggers, “Nothing good can happen when two men are trapped alone in a giant phallus.”

Apart from the lighthouse being an obvious symbol of unachievable power and masculinity, gender roles are unambiguous since the beginning: Ephraim is left to do manual chores, or forced to be the woman of the house. Meanwhile, Thomas is free to climb the giant lighthouse and bask nakedly in its glory, like a moth drawn to a flame. Thomas always speaks of the lighthouse in feminine terms, referring to the tower as a better wife than any living woman.

According to Dafoe, the homoeroticism of the film does speak to some aspects of identity and what it means to be a man. Ephraim clearly yearns for the approval of the older Thomas, the unquestionable father figure, and begs for his turn up at the lighthouse. There also seems to be much talk about lobsters—do with that what you will. Eggers expanded on that to say that the queer subtext was always at the heart of the movie’s central relationship, but that “the whole thing is about power dynamics, so it is about Willem pushing, pushing, pushing, pushing, pushing. And there’s pent-up anger and pent-up erotic energy and pent-up smells. Where is that breaking point?”

It appears that the breaking point comes the night where Ephraim “spills his beans.” He admits that his real name is Thomas Howard and that he took the name of a man whose death he caused. Thomas, of course, denies him his name, calling him “Tommy” and psychologically punishing him for his truthfulness. This scene is pivotal, as it opens up two very important psychoanalytic interpretations.

First, both keepers have the same name. This could be interpreted as the two keepers being two sides of a coin, or the same individual in a cycle of life. Secondly, Thomas Howard’s taking the name of his deceased employer can be interpreted as an indication to a more intimate relationship, as Michaela Barton writes at Flipscreen: “The act of Tommy taking his name…[is] almost like the tradition of taking your partner’s name after marriage.” This not only sets Ephraim/Tommy again in the position of the wife but also equates marriage and sexuality with death.

There is much sailor talk throughout the film of “giving yourself to her [the ocean]” as you die, just as you “give yourself” when you marry or have sex. Sexuality is definitely rampant, as Ephraim/Tommy carries and imagines a mermaid—the only achievable figure of femininity in the island, and a creature of the sea who is as terrible as she is beautiful. He holds the mermaid figurine and masturbates while having visions of the lighthouse and Thomas naked, finally imagining the mermaid taking his body to the deep, where Tommy Winslow forever disappears. It is as the older Thomas chanted: “The sea takes it away, leaving nothing for the harpies but the souls of dead sailors.” For as we know, when you die, not even your soul belongs to you, you must hand it over to be reborn as a seagull. It becomes difficult to distinguish between the sea and death, and marriage and possession (remember Thomas’ ruined life due to his possessiveness of his lighthouse/wife).

As the rations run out, the weather worsens (destroying the house, the only remnant of society). We no longer know if we have been on the island weeks or months, or if what we witness is real or dreamed. Who truly smashed the boat? Who chased who with an ax?

Ephraim/Tommy has a vision in which, after finding himself unable to climb the tower, he is grabbed by a naked Thomas, whose eyes are as potent and hypnotic as those of the lighthouse.

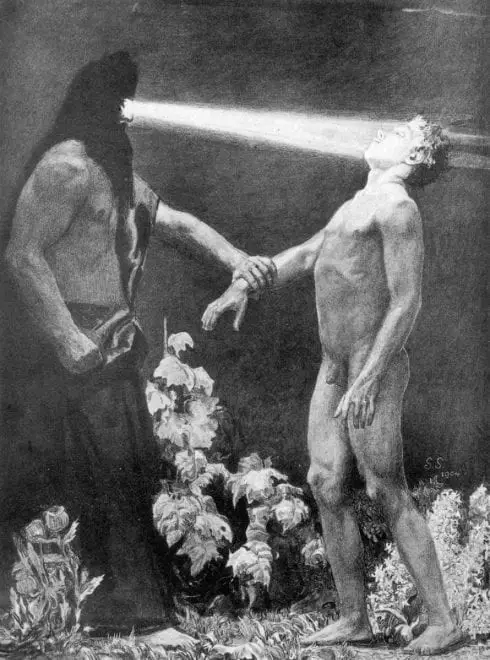

The composition of this shot was inspired by a painting called Hypnosis by Sascha Schneider, a 1940s German artist whose work has been read through many queer interpretations.

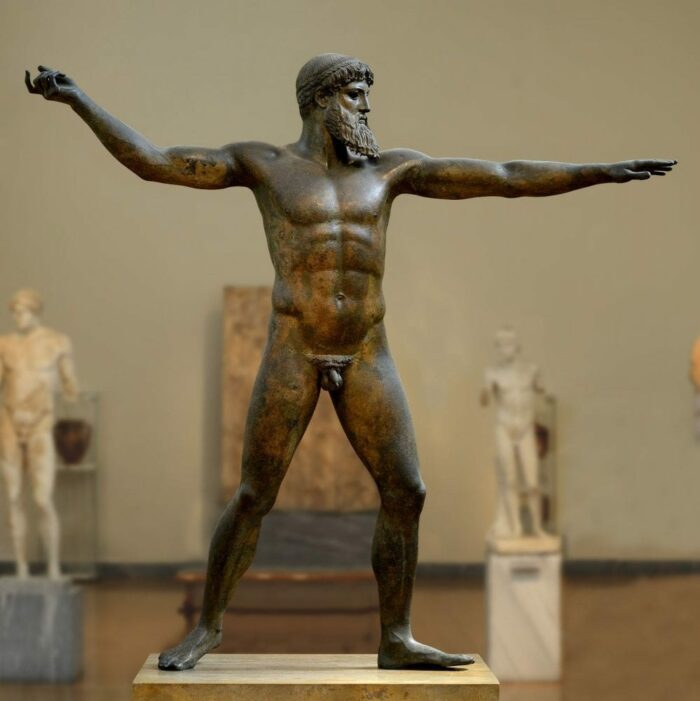

However, Thomas’ stance is different than that of the hypnotizer in Schneider’s painting. Thomas’ stance and position are strikingly similar to that of a famous bronze statue, the Artemision Bronze, which depicts either Zeus or the sea god Poseidon.

National Archaeological Museum of Athens , CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

If we follow this hypothesis, the fact that Thomas is modeled after Poseidon (or Zeus) makes Ephraim/Tommy Prometheus, a prophecy-telling ocean god who serves Poseidon. The younger man is shown throughout the movie with tentacles and sea creatures stuck to his body and dies in a similar manner to Prometheus, who is condemned by Poseidon and punished by Zeus to be chained to a rock on a mountain peak where birds tear out and eat his liver for eternity.

The mythological legend of the birth of Zeus is also important. According to the legend, the titan Kronus ate all of his children and also attempted to eat Zeus, who had to fight back and kill his father in return. In the film, Thomas, the father, had either driven his previous wickie to madness or killed him, and he plans to do the same to Ephraim/Tommy. So who is Zeus, who is Kronus, and who is the murderer?

The similarity between these art pieces is subject to interpretation, but the mythological and artistic influences on the film are undeniable. In the end, Prometheus was punished for defying the Olympians, so why is Ephraim/Tommy punished?

The answer lies in the lighthouse, or rather underneath it. After all, what’s underneath the imposing edifice of unachievable masculinity? In an early scene, both keepers dig at the base for rations only to find alcohol, their gateway to madness, instead. Then, Ephraim/Tommy uses the same spot in the base of the lighthouse to bury his Oedipal father figure (I am positive Carl Jung would have loved this movie).

This is his grave mistake, however, as one cannot debase and bury one’s father alive, along with the projection of all unfulfilled dreams and self-loathing, for he always comes back to haunt his son.

Because he is not able to accept Thomas, the other side of him, and instead allows himself to wallow in madness and self-pitying despair, Ephraim/Tommy falls from the lighthouse. Its light was, quite literally, too much for him to handle. So our antihero falls to his death, not having realized himself as an individual nor as a man.

The tragedy of the story is that he does not die in the ocean, so he can never be dragged to infinity and lose himself. For his selfishness, the man born Thomas Winslow is condemned to offer his body to the souls of honest sailors for eternity, never dying but never being truly alive.