The films of Jacques Rivette are one of the bigger blind spots in my experience of world cinema. True, the French New Wave has never been my speed exactly and the lengthy run-times of his films are enough to discourage curiosity, but this year’s festival opened with a restoration of his 1969 film L’Amour Fou, and so my first Cannes film became my first Jacques Rivette as well, and I settled in for a very long four-and-a-quarter hours of relationship drama and discourse upon the nature of drama itself, surpassing The Irishman as the longest span of time for which I’ve ever glued myself to a cinema seat.

I was one of the few who stayed the course, with my corner row of five whittled down to just two (including me) by the time the credits rolled and the somewhat thin standing ovation began. So no, L’Amour Fou is not a casual watch and unlikely to attract outside audiences, but the film is paced and unfurls in such a naturalistic, quotidian way that it feels oddly mesmerising. I was certainly confined to my seat by more than a stubborn desire to hold onto my “has never walked out of a cinema” badge. L’Amour Fou is occasionally droll, intermittently fascinating, rigorously intellectual, and performed with such a studious impression of spontaneity that the lines between documentary and performance become blurred almost organically.

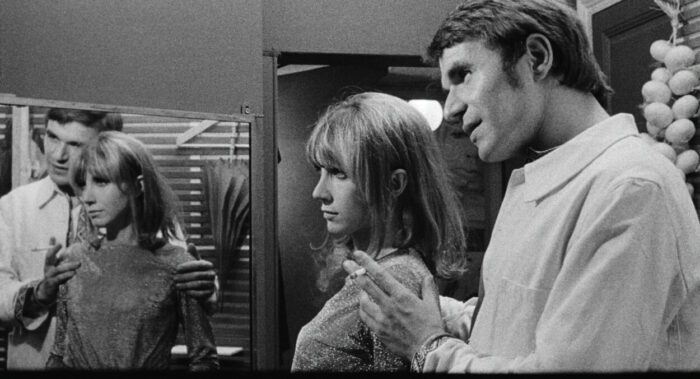

Following an attempt by a theatre company to stage a production of Jean Racine’s Andromaque—a retelling of the story of Hector’s devoted widow, forced to bargain for her son’s life after the fall of Troy—the film begins with the director mysteriously absent on opening night, before flashing back three weeks to the start of rehearsals, when the trouble first began. Sebastian (Jean-Pierre Kalfon) has just begun leading his dramatic company into the rehearsals for their production when the actor interpreting the crucial role of Hermione—Andromache’s spiteful rival—abruptly drops out after bridling at Sebastian’s overbearing attempts to direct her. The trouble is, that actor is his wife Claire (Bulle Ogier), and to compound the issue, her replacement is his even-tempered and statuesque ex-wife Marta (Josee Destoop).

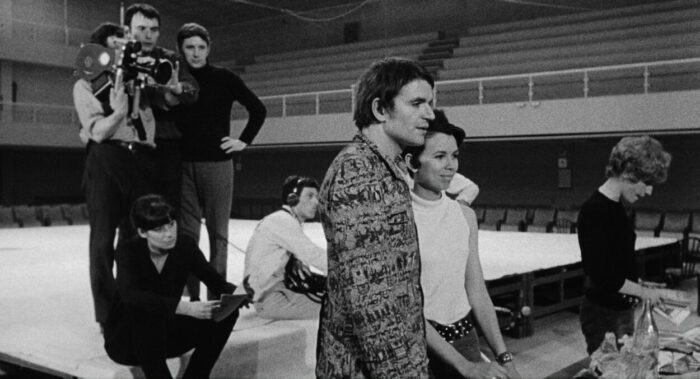

All seem to handle the incident like professionals at first, but it gnaws at Claire and as Sebastian devotes himself more and more into his play—and loses interest in her once she is no longer actively involved in it—she falls into a jealous depression, convinced he is having an affair, if not with Marta then with any other of the women in the company who make her feel inadequate. The relationship comes under such strain as her insistent attention and his disinterest mount that their codependency becomes increasingly harmful and toxic. As if that’s not enough, a documentary film crew is observing the three-week rehearsal process, spotlighting every one of Sebastian’s frustrations and confusions and putting his long-suffering cast in the crossfire, left to tiptoe around their director and his rapidly disintegrating marriage.

Ogier’s Claire is a beleaguered and unhappy young woman in a relationship with a huge status and power imbalance in which she feels insecure. I’m pretty confident that Claire has what we would now call ADHD and certainly depression compounded by serious trust issues. Sebastian is harder to diagnose, and perhaps more mundanely egotistical, failing to put the work in to reassure his wife, instead becoming defensively aloof. Whether he really is betraying her love or if he soon will is a key mystery we follow throughout the film’s first hour. He certainly considers cheating on her, all day he’s surrounded by beautiful, intelligent women with whom he’s starting to have the kind of connection he used to have with her. If he doesn’t still carry a torch for Marta he at least still has the hots for her, seeing her as an agreeable alternative to the complicated and difficult Claire, and embarrassing himself like a horny teenager when alone with her. But he refuses to validate Claire’s fears but nor does he hear them out or do anything to alleviate them, too consumed is he in his pride and his play, as both rot each other on the vine.

Oscillating at times violently between determined and unaffected realism and intense surrealism, the two are ultimately eluded in the goofy behavior of our lovers on the rare occasions when they in sync and feed off one another’s oddball energy in a way that is instantly familiar and intensely relatable, doing some much needed work of showing us their relationship when it’s working, when it’s isolated from the outside world and both are on a temporary high. The two unquestionably love one another and the film explores their jealousy and insecurity far more astutely than many a pseudo intellectual drama about the artistic personality. There’s a consistent humility to the way the film approaches the subjects under discussion, undercutting itself with humor or sincere emotion to stop things becoming too dryly intellectual or self-serving. Sebastian’s obsessive devotion to his craft feeds much of the intellectual debate in the film, and as interesting as those debates are, its obvious he’s taking the whole thing too seriously and overthinking it, convinced as he is that he’s on the verge of reinventing the wheel of theater.

Its relationship to Andromaque is similar in many ways to Drive My Car and its use of Chekov’s Uncle Vanya as the film devotes much of its extensive runtime to watching the rehearsals, often inter-cut with the offstage drama. In fact, Drive My Car often feels like a bit of a distant cousin, with the agony of the director filtering down in piecemeal to the actors through strange requests and oblique silences. On the surface of it, the two stories of Andromaque and L’Amour Fou are unified by the underlying emotions of love, yearning, bitterness and control, but these scenes primary function is to explore the mechanisms of artistic direction. The rehearsal tactic of marking the end of each Alexandrine line with a clapper, which becomes increasingly elaborate and absurd as the rehearsals go on, mirrors the editing punches and kicks strewn throughout the feature, reminding you of the New Wave blood in the film’s veins.

Meanwhile, as the documentary crew records the process of rehearsals, they often stray uncomfortably close to the insecurities of the participants, who find themselves left to avert questions about the director’s increasingly erratic behavior and the stalled rehearsal process. The film delineates between the two sources of footage by filming the documentarian’s footage in grainier 16mm as opposed to the film’s standard much cleaner 35mm. These interviews with the cast and director are among its most absorbing moments, as their illuminating answers provide insight into the supporting characters and their frustrations, priorities and concerns, as well as some interesting discussions on the dramatic process.

The performances are never less than effortlessly convincing from start to finish, drawing you into this relationship and its dynamics, and in the good and bad and making you feel these two people alive and feeling intensely about one another. The supporting cast equally fantastic both in the stilted classical delivery in the play, all that totally unmannered and credible performances off as their off stage selves. What really brings L’Amour Fou to life, though is the incisive quality of the writing, which has naturalism and perceptiveness that feels rare even today let alone 60 years ago, when the film was made. Never losing a vital spontaneity and sense of improvisation. This sense of realism is what keeps you engaged.

For many L’Amour Fou’s length will be too testing, as it was for many of those in the screening room with me who failed the endurance test. But its commitment to realism and fragmentary structure make its duration not only justifiable but a lot easier to bear. I can certainly see why many of these scenes would be subject to the knife of a less headstrong filmmaker, but they are a tool in the films repertoire, it’s a film as much about the collaborative artistic process as it is love in all its pain, joy and discomfort. The way it interleaves these two themes may feel laborious at times: perhaps one wonders if either is best served by being forced to share a screen for more than four hours. The interplay between the two is tenuous and will likely test the patience of most audiences, but both are undertaken with no paucity of thought and their simultaneous examination gives the film much of its life and veracity. The lives of these characters are polysemic and that very messiness is essential to L’Amour Fou’s tone and affect. Life and art claw at one another desperate for the other’s attention.