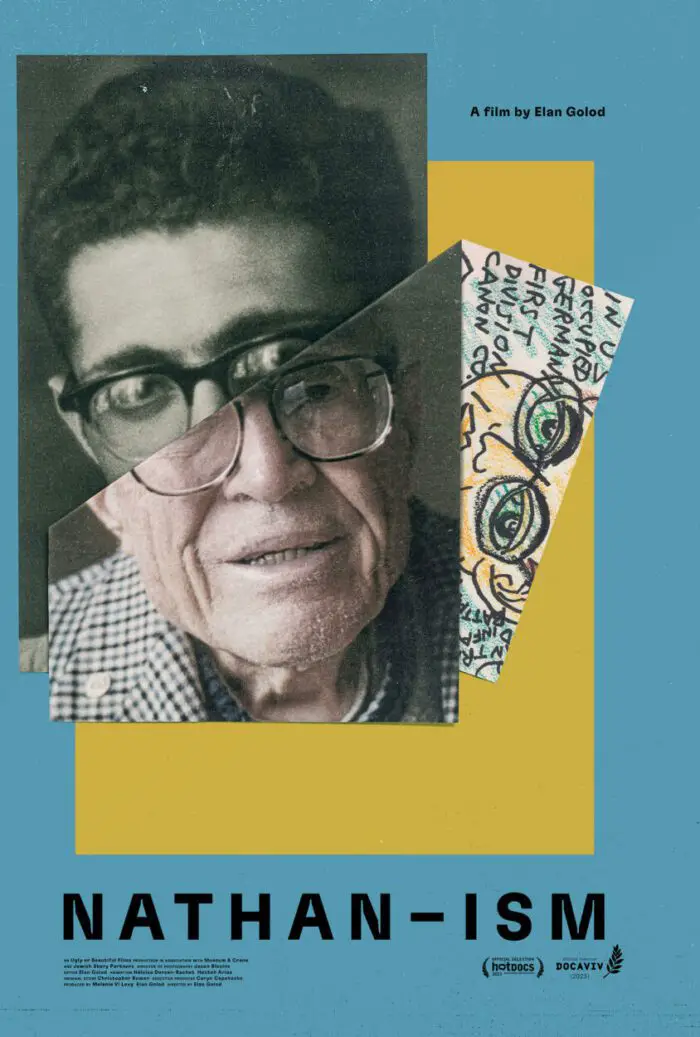

Filmmaker Elan Golod is the director of the new documentary Nathan-ism, which recently premiered at Hot Docs and Toronto International Film Festival. His film focuses on the life and art of a man named Nathan Hilu, a Jewish Army private in World War II whose assignment, for a time, was to guard Nazi war criminals—Albert Speer, Hermann Göring, Rudolf Hess and others—at the Nuremberg trials. His was an experience that forever inspired young Nathan, who spent the next 70 years obsessively creating a visual narrative from his memories in the form of stark black-and-white drawings, annotated with verbal commentary and shaded with crayons. His artwork is remarkable, his stories incredible—and perhaps too much so to believe.

Nathan-ism is a film that explores the relationship between art and truth, fact and memory, and does so with no small amount of Nathan Hilu’s own artwork, rendered at times in striking animations by Héloïse Dorsan Rachet. In a time of rampant antisemitism and Holocaust denialism, Nathan-ism offers us all a reminder to heed the lessons of the past as we embark upon the future.

Film Obsessive’s Executive Editor J Paul Johnson interviewed director Elan Golod shortly after the film’s appearance at Toronto to discuss the film’s subject, making, and themes. The interview has been edited for space and clarity.

Film Obsessive: Your new documentary film Nathan-ism recently screened at Hot Docs and at Toronto International Film Festival. For readers who aren’t yet familiar with the film, can I just ask you to tell us a little bit about it?

Elan Golod: The film is about an elderly outsider artist named Nathan Hilu, who as a young man, was one of the few Jewish American soldiers to guard the Nazis at the Nuremberg Trials. That experience fueled his creative output for the rest of his life. He created a lot of drawings based on those experiences, and I ended up following him for the last four years of his life.

Now that your film is completed and it’s out in front of audiences, what do you feel like you’ve learned from Nathan Hilu, your subject, and from his artwork?

I think I learned about the relationship between historical truth versus personal truth, and that those things should be in relationship to each other. You can’t focus strictly on what we learned in the history books. The oral histories are just as important and should be used together with archival research. And those should all be part of the study of history.

This was a pretty complex undertaking as it turned out. About how long did it take you to bring Nathan-ism to fruition from your first meeting with Nathan to the film’s eventual completion?

Up until now, it’s been about an eight-year long-journey. I came across Nathan’s story when I read an article about him after he had had a small retrospective at Hebrew Union College Museum. And that was about early 2015. I got his information and cold-called him at first. He was a little paranoid. He didn’t quite understand what I wanted from him, but I was able to gain his trust and show him that I really wanted to showcase his full story. And we became friends and I started filming him on average once a week. That ended up being a four-year-long process of filming him. And then I continued editing the film over the following four years while I was working on some other projects as well.

There was a moment in your documentary that it seemed like it took on a dimension that you hadn’t really planned when you felt yourself compelled to investigate just how truthful to the historical records some of his artwork was. You’re not the first documentary filmmaker to change directions midstream, but I’m just wondering if that was a part of the process that was disconcerting for you or if you could just describe what that felt like during those moments.

This wasn’t my initial direction but, after maybe a year of filming, I got the sense that there was a deeper story there. That story about memory that I wanted to explore. Listening to Nathan’s stories, some of them are so fantastical that you’re not quite sure what to believe. And I wanted to take the viewer on that journey with me. I wasn’t sure initially how much we’d be able to verify or not, but the research took us in some interesting directions, as you can see in the film. It was definitely troubling when it came time to confront Nathan about our findings. I didn’t want to ruin the relationship that we had built, but I felt that it was important for the film to at least make an effort to see how he would react. And I think it showed some interesting sides of him in terms of like his memory.

It’s a really interesting ethical question in that, as a filmmaker, you’ve got your obligations to your audience and you’ve got obligations to your subject. And it seems like there’s a moment there in Nathan-ism where the two are directly colliding. Can you take what he says and what he draws and what he writes at face value, or do you owe it to your audience as well to explore that? So I just want to take you to that moment in the film where you confront him. Can you describe what that was like? Just who was in the room with you and what was the mood or feeling like at that moment?

It was just myself and to camera operator, friends of mine. His apartment is relatively small, so we never had a very big crew with us. It definitely was the most tense day of filming. I feel like for that period, I don’t know if he felt a little betrayed in terms of our relationship. I’m glad to say that feeling didn’t last very long. The next time that we visited him, the following week, he was back to his normal self and was happy to continue our relationship the way it had been. But that day was not not an easy day for anybody in that room. It was even even my camera operators who didn’t know Nathan quite as well as I did were, you know, we felt that it was a very tense experience.

That really comes across on screen. Could you just talk a little bit about how some of your prior experience, whether it’s academics, military, or prior projects, helped prepare you for making this film?

Interestingly enough, entrance into film work was through my experience serving in the Israeli Army. Part of my Army service was making training videos for the Israeli Army. And I think having the experience of being a young 18-year-old soldier, I didn’t have the experience of guarding top-level Nazis, but I did have the experience of understanding duty at such a young age. And I could place myself into to Nathan’s shoes to understand what he was going through.

After my Army service, I studied film at NYU, where I focused mostly on editing work. And I’ve been working in New York as an editor. And I think my experiences as an editor helped me learn how to find the story in the edit because I didn’t have a roadmap of where where this story was going. So a lot of the film was found later on with digging through the 300 hours of footage that we had with Nathan and just piecing it together and seeing what structure could tell the story in the most intriguing way.

Wow, so you took 300 hours down to about 80 minutes. Thank you for doing that! I’m also interested in just the sometimes copious amount of research that goes into the process of making documentaries. You found yourself, obviously, a handful of really wonderful interviewees here. You worked with archival footage and news items, military records and more. Can you just talk a little bit about the work that a documentary filmmaker like yourself has to do that doesn’t always involve pointing the camera at a subject?

It’s funny, but after this project, I think my wife comments on just how many books we now have about Nazi Germany. And we’re a Jewish household with lots of books with swastikas on them, which was an interesting byproduct of working on this film. I knew the basics about the Nuremberg Trials, but I had to immerse myself much deeper than that in order to tell as accurate a story to piece together. How much of Nathan’s stories could have been true? What he may have conflated with stuff he had read. There a lot of time spent in research that wasn’t actually spent filming Nathan.

I wanted to ask too about the animations, which are really quite striking. I felt like they really helped bring Nathan’s artwork to life. Were they something that you had planned or imagined from the very beginning in your documentary, or was there a moment where you decided it was a step that you wanted to take?

I felt like I wanted to bring his artwork to life, if possible. But it took a while until I found the right animator who I thought could do his work justice and make it seem as authentic as possible. And I came across this animator, Héloïse Dorsan Rachet, she was actually based in Paris, but she had worked on a film that a colleague of mine had made. And something about her work had the childlike innocence that I saw in a lot of Nathan’s work. And I sent her a bunch of references from his work, and we did numerous tests to see how to make it feel like like these were his works. And, you know, and not just animation that’s somewhat reminiscent of his work, but almost every animation sequence in the film is based on specific drawings that she took and brought to life in different ways.

They do add, I think, a lovely element to the film. I think they also seem to me, at least from the outside, to be really quite faithful to his own work, not taking it in two different direction at all. What’s next for Nathan-ism in terms of distribution and exhibition? And then of course, what’s next for you?

We are in the middle of the festival rollout for the film. We have several festivals coming up this fall. Our next festival is at the Heartland Film Festival in Indianapolis and we’ll be at Hot Springs in Arkansas. We have an exciting New York premiere coming up that I can’t officially publicize. But one of the most exciting things about our rollout, which I think would be very poignant for Nathan’s legacies, that in February of next year we’ve been invited to screen the film in the court room in Nuremberg.

That is truly exciting. Congratulations to you on all the success of Nathan-ism so far. I sincerely hope that it meets and reaches the widest audience possible. It really is a lovely film. It’s audacious in its own way, as is its subject, and it really deserves to be seen as much as possible.

I’m glad you appreciate the film.