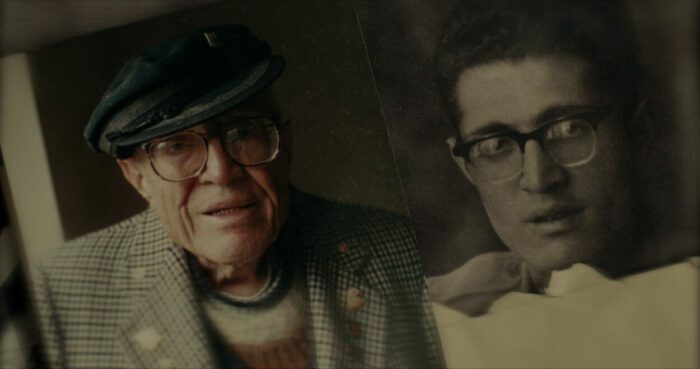

Nathan Hilu, born to Syrian Jewish immigrants to New York, served in the U.S. Army in World War II, where among his assignments was to guard the top Nazi war criminals at the Nuremberg trials. Standing next to history itself, an armed Jew guarding the killers of millions of Jews, would make in itself for a fascinating documentary. But as the saying goes, truth is stranger than fiction, and in the compelling film Nathan-ism, Elan Golod mines Nathan’s rich history as it explodes in his feverish artwork, a voluble, volcanic expression of memories and emotions. Even in his 80s, Nathan is an irrepressible, fascinating subject, and Nathan-ism brings his art to life through moving animations and a rich study of the complex relationship between truth and art, history and memory.

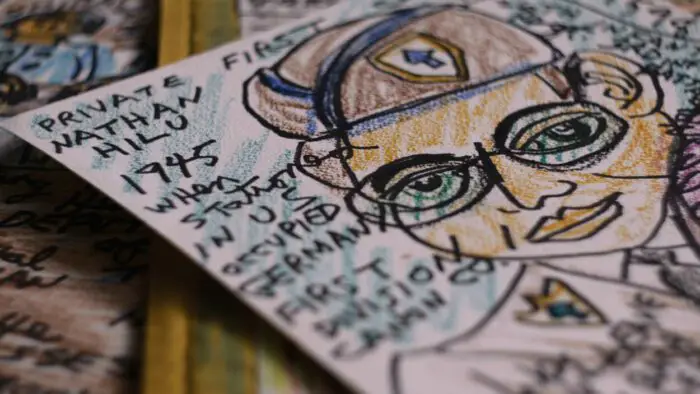

Nathan might best be described as an “outsider artist,” someone unheralded and largely unknown but whose considerable body of work doesn’t really fit any established paradigm or movement. In Nathan-ism, he is nearly always drawing, hunched tightly over his board, his arthritic hands gnarled about a thick Sharpie, stabbing out crude faces and figures from his rich past, scrawling out captions and comments in their margins, shading and coloring his collages with crayons. He’s done this for years, cranking out images of himself as a young man at sentry, guarding the likes of Rudolf Hess, Hermann Göring, and Albert Speer, others depicting the Führer himself in all his dictatorial fury.

How does Nathan describe his own art? It’s not something that fits into any known movement, he says. There’s a lot of so called -isms in art: Cubism, Expressionism, Modernism. His is simply, as he says, his own. “Nathan-ism,” he call it. Over the years and as Nathan has aged, his artwork has become even more feverish, an almost subconscious, irrepressible font of memory. That it is so is perfectly understandable if one can even imagine a young Jew first learning of the atrocities of the Holocaust while standing guard at the Nuremberg Trials.

Some of Nathan’s artwork records events that complicate, perhaps even contradict, the historical record. One of his drawings in particular depicts Göring’s wife visiting the Nazi criminal in prison, a wordless visit punctuated by a long kiss that surreptitiously slipped him a cyanide capsule he used to commit suicide rather than face his sentenced fate of death by hanging. It’s a version of the story that no other account confirms, and it begs the question that dogs much of Golod’s documentary: is it true?

That question—Is It True?—motivates so many excellent documentaries that explore the boundaries between truth and fiction. Golod takes it upon himself to investigate his subject Nathan’s past, hoping to triangulate his findings: is Nathan’s art to be taken at its word for the events it depicts? As Golod pursues the truth of Nathan’s service history—the records of which were destroyed in a disastrous fire in 1973 at the National Personnel Records Center (NPRC), where some 16-18 million files burned. Discerning fact from fiction is no simple task when the official record has been erased. But at the same time, it’s more important than ever to be able to do so in an era of fervent Holocaust denialism and distortion.

Golod’s film relies, alongside its interviews and depictions of Nathan Hilu, on interviews with Eli Rosenbaum, the famous “Nazi Hunter” who led the U.S. Department of Justice’s Office of Special Investigations; art historian and curator Laura Kruger, who works with Nathan on a showing of his art; Lori Berdak Miller, an archival research at the NARA-St. Louis Archives whose attention to detail unlocks a key finding in Nathan’s history; and just a few others. The focus here is on Golod’s extraordinary subject, Nathan Hilu, and his extraordinary artwork, but these few select interviews lend the necessary disciplinary expertise to characterize—and interrogate—Nathan and his artwork.

For as irrepressible, irascible, and engaging as Nathan Hilu is as a documentary subject, Golod does not, to his credit here, rely only on Nathan’s recollection. Confronting the old man on camera—he’s clearly more comfortable drawing than interviewing—makes for an uncomfortable moment a little like when Bing Liu confronts his mother on camera in Minding the Gap. It’s a necessary, if difficult, moment in the process of learning the truth.

In Nathan-ism, though, the truth is not the last word. The old man’s art, whatever its exact relationship to the facts of historical record, remains. And it’s fascinating stuff. Golod’s film would be excellent if it merely presented Nathan Hilu and his lifetime of art and memory. That it dares to challenge its truthfulness and examine the very fabric of the relationship between truth and art makes it astounding, a film that will resonate with viewers long, long after its closing credits fade.

It may be practically parenthetical to say so at this point, but the film is, for all its thematic complexity, expertly shot, composed, and directed. Golod, an experienced editor directing his first full-length documentary feature, clearly relishes in the richness of Nathan’s story. (Golod himself served in the military in Israel before settling into film production in New York.) Nathan-ism keeps a brisk pace, segueing adroitly between scenes with Nathan and the other interviewees, and Jason Blevin’s cinematography captures Nathan’s art with loving, close-up detail. For a traditionally expository-participatory documentary relying on presentation of artifacts and interviews with participants and experts, Nathan-ism is as rich in mise-en-scene as one can imagine. An original score composed by Christopher Bowen and sprightly animations of Nathan’s art by Héloïse Dorsan-Rachet bring the past to life.

For all of Nathan-ism‘s technical merit, it’s a film that will engage the mind and the heart alike. Those of us who’ve spent time with the aged know it can’t last forever. And Nathan Hilu is a man worth spending time with. Whatever the facts of history, his remarkable drawings depict him as a young Jewish soldier confronted with the atrocities of the Holocaust, learning of them for the first time at Nuremberg, where he met and knew the architects of its evils first-hand. His art, however it might be categorized or interpreted, deserves an audience, and so too does this remarkable, affecting documentary attesting to the complexity of the man and his work.

Nathan-ism premiered at Hot Docs 2023 and was the subject of a special screening at the 2023 Toronto International Film Festival.

Mr. Johnson,

Great article, but a slight correction if you could note it. Would make NARA St Louis very happy.

Actually, my research was at the NARA-St. Louis Archives, not NPRC. NPRC houses the non archival files, which I can explain more if needed. I feel very honored to help on this project

I’ve made that correction. Thanks for pointing it out, and I appreciated your contribution to this wonderful film!