One could make a case that composer Ennio Morricone influenced the course of cinema in the 20th century as much as anyone. In fact, that’s exactly what Giuseppi Tornatore, director of Cinema Paradiso, known for one of Morricone’s more conventional if no less affecting scores, does in his documentary titled Ennio. At over two and a half hours, the film’s length exceeds most of its type by a full hour, but I can think of no composer more deserving of a full, rich, unfettered documentary treatment than Morricone, who remarkably continued to compose right up to his death at age 91 in 2020, leaving behind an unparalleled body of work.

In Ennio, Tornatore leaves almost nothing out, not even his subject’s infancy, in covering Morricone’s life story. The film begins with the nonagenarian’s morning stretching routine interspersed—a bit awkwardly—with comments from Morricone’s many collaborators, friends, and fans on his art and work ethic. From there, the film’s first act digs deep into the Morricone family archives to uncover the boy’s first performances, his relationship with his demanding father, and his classical musical education. You know a documentary will treat its subject fully when its chronology begins with images of him naked as an infant.

For casual fans of Morricone who might know only of his work with Sergeo Leone, the film’s first act might feel like something of an exercise in coverage. But Tornatore knows what he is doing: it’s crucial for our understanding of Morricone’s unique artistry to understand his classical education in music, his apprenticeship under Goffredo Petrassi, and his work as a studio arranger and ghost composer of popular music, all of which would deeply inform his work in the cinema. Morricone was also transfixed by a John Cage concert in which the avant-garde American performed with random found objects, calling into question the very nature of music performed by trained musicians with traditional instruments; for Cage, and later for Morricone, anything might be made music.

When Morricone was tabbed by Sergeo Leone for music for his loose adaptation of Kurosawa’s Yojimbo—A Fistful of Dollars / Per un pugno di dollari—his effort reflected all of these influences, molded together in a piece unlike anyone had ever heard before. It used nontraditional instrumentation: handclaps, whistles, grunts, a triangle, and the instrument of the rock-and-roll moment, the electric guitar, for the main theme, and a melodramatic flourish of operatic orchestration for the finale. Set against the film’s rotoscoped title sequence or its final dirty, dusty shootout, Morricone made something new and fresh to equal—and perhaps even surpass—the director’s reworking of the oldest American genre through Kurosawa into something truly transnational and postmodern.

Morricone and Leone, who realized they had been elementary schoolmates, forged a bond that lasted for two more decades and even more recognizable, famous scores, especially for The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly and Once Upon a Time in the West. It is not a stretch to say that, especially in his work on Leone’s films, Morricone rewrote what film music could be. It was no longer a simple exercise in matching existing compositions to already-shot screen action but in his case, creating something new and expressly cinematic that was as organic a part of the film’s whole fabric as its script, its cinematography, or its cast.

In Ennio, Tornatore takes his time making this case, especially with the Leone films. Once Upon a Time in the West in particular is famous for using ambient sounds as a part of its musical score and creating leitmotifs for individual characterization. And the main theme in The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly is as recognizable as any melody of the modern era. Tornatore makes the case that Morricone could both experiment, in the most unpredictable and successful of ways, as he does in these films and in Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion, and hew to convention, as he does in Tornatore’s most famous film, Cinema Paradiso.

Perhaps due to modesty, that latter practically gets short shrift. The love theme for Cinema Paradiso may be Morricone’s most recognizable romantic score, but even in Tornatore’s ode to cinema’s past, it’s used in a remarkable way, connecting with the film’s ending montage of censored kisses in one of the most moving sequences in all of cinema. It’s remarkable that a 156-minute documentary of Morricone’s career doesn’t have the time even to reflect on that specific scene.

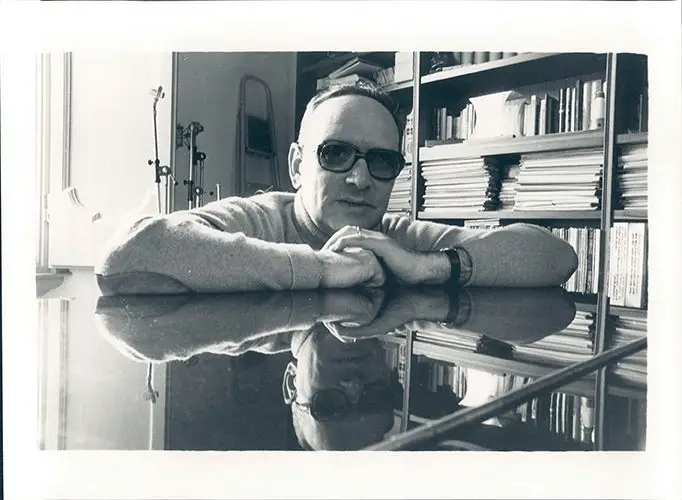

There is time, though, for plenty of gentle humor and emotional reflection throughout, both from Morricone, whom Tornatore filmed at length before his death, and from many others. Morricone is insightful, proud, sentimental, and objective about his work, unafraid of self-criticism but also more than content—as he should be!—with much of his accomplishment. Tornatore’s interviewees include himself, of course, Bernardo Bertolucci, Marco Bellocchio, Giuliano Montaldo, Dario Argento, Clint Eastwood, Joan Baez, Quentin Tarantino, Bruce Springsteen, Pat Metheny, Hans Zimmer, Wong Kar-Wai, and many others. (My favorite is Oliver Stone, who comes off as a bit of a dunce for having asked Morricone to score a sequence like a Tom and Jerry cartoon, a request at which the composer took no small amount of perfectly deserved offense.)

Morricone composed, in his long career, over 400 film and television scores, 100 classical works, and scores of individual and collaborative pop compositions. This review—a good deal shorter than the documentary Ennio—can mention only a few of them. (Check out Film Obsessive’s favorite scores of his from the ’80s and ’90s.) Any fan of modern cinema or modern music will be well served by this loving, sweet, informative, and nearly exhaustive documentary charting and analyzing Morricone’s remarkable career. It’s one that changed what we think of when we think of film music, and it’s one that deserves this full and deeply appreciative recounting.