Over 25 years ago, Slam was a surprise hit at Sundance, winning its Grand Prize. Gritty and realistic, the film’s depiction of life on the streets and in prison earned it critical acclaim and the admiration of audiences. Two and a half decades later, the circumstances informing its narrative remain too little changed, but Marc Levin’s film stands today as a powerful testament to the challenges facing young Black men in American’s cities and to the potential of expressive performance, largely thanks to its compelling leads Saul Williams and Sonja Sohn. With help from the Sundance Institute, the Academy of Motion Pictures, and UCLA, a digital restoration of Slam is now earning a theatrical release and distribution by Kino Lorber: it speaks as clearly and loudly as it did in 1998.

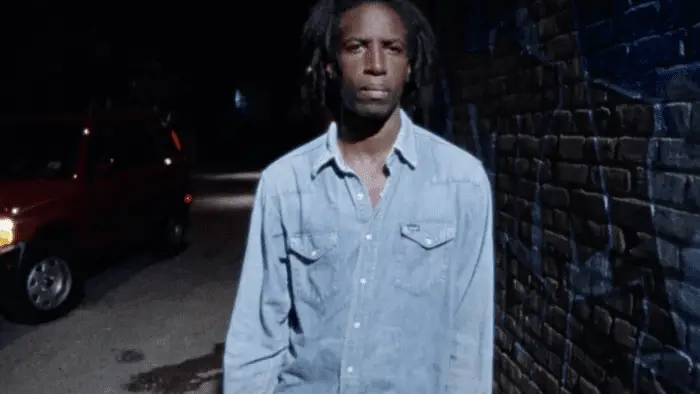

Williams plays Raymond (Ray) Joshua, a quiet young man making his way on the streets of Washington, D.C. by selling marijuana (in amounts legal there today) and otherwise trying to stay clear of the city’s rampant gang violence. But he can’t for long: a friend of his is shot during a deal and trying to make his way clear, Raymond is arrested on a petty drug charge and sent—like so many other young Black men—to prison. By nature and by choice, Raymond is avowedly nonviolent, standing up to every challenge with words that convey his inner strength. In prison he’s the object of two gangs’ attention and enmeshed in their violence, but he stands strong in his resolve, taking inspiration from a gang elder (Bonz Malone) who sees in Raymond a glimmer of his potential.

Another inspiration comes when an English teacher, Lauren (Sohn), who teaches classes and workshops for the inmates, meets Raymond and inspires him with her own passion for poetry and the power of creative expression. It’s something of a fluke of the justice system that Raymond earns his freedom—especially when so many others on similar charges do not—but with Lauren’s help and eventually her love he makes the most of his opportunity to avoid becoming another victim of the racist criminal justice system. And he finds, ultimately, his true passion in life in spoken word expression, the “slam” that’s all poetry, not prison, and the film’s testament to the power of language.

The spoken word movement that Slam depicts was one that aimed to democratize the voices of poetry for new generations of young, black male and female artists, following how hip-hop and rap had brought new voices to the mainstream of contemporary music in the prior decade, rippling out all the way through into the broader pop culture and even academia. Slam makes these powerful performances of poetic expression, delivered with pure passion and dextrous wordplay, as both Williams (who wrote Slam‘s script as well as starred as its lead) and Sohn double down with mesmerizing deliveries in the film’s final, euphoric act.

Shot on location in D.C.’s streets and prison, Slam followed director Marc Levin’s Emmy Award-winning HBO documentary, Thug Life. Williams and Levin collaborated with the prison’s warden and corrections head and cast real-life correction officers and detainees who improvised their scenes and dialogue. The loose structure of the script, on-location shooting, and casting of non-professional actors in supporting roles, combined with cinematographer Mark Benjamin’s documentary shooting style, makes Slam a film informed by neo-Neorealism, a hybrid the makers called “Drama Verité.” (IMDB categorizes Slam as “Documentary/Drama” even if its lead characters and situations are fictional and played by professional actors.)

The looseness of the script, forged in part from its extemporaneous conceit, gives Slam the documentary feel its makers sought as they hoped to highlight the injustices of the “war on drugs” that made the criminal justice system so dysfunctional and destructive. In that regard, Slam feels a bit more like something more like an optimistic version of La Haine than many of the more tightly-scripted and carefully structured ‘hood films that preceded it in the 1990s. Its structural looseness may feel at times unfocused, but it’s also an integral element of the film’s narrative, a randomness one can associate with the violence that can break out at any time, at any place, and the ever-present surveillance of a law enforcement bent on incarceration of what they used to characterize as “superpredators.”

Slam deserves a second look. Its focus on spoken-word performance helped inspire a generation of new poets, and its depiction of the incarceration of young black men for petty crime is one that continues to plague the country broadly and D.C. specifically. Just look, for one compelling example, at the Davy Rothbart-directed documentary 17 Blocks. Slam‘s prescience, its topicality, its performances, and its verisimilitude, heightened by a score from DJ Spooky, make it a film well worth revisiting.

Digitally restored from the film’s original 35mm interpositive with a new DCP created in collaboration between Sundance Institute, the Academy Film Archive, the UCLA Film & Television Archive, and Lionsgate, Slam will open theatrically April 26, 2024 in New York City at the Roxy Cinema before releasing on Blu-ray (with audio commentary from Levin and Malone and selected behind-the-scenes footage bonus features) May 21.