Bill Duke’s Deep Cover (1992) is one of those films that fortunately came to be something far different—and far greater—than its creators originally intended or perhaps could even imagine. Evolving through several preproduction iterations from a straightforward takedown of a drug cartel to a stylish, evocative, tautly wound thriller exploring black masculinity, Deep Cover hybridizes the neo-noir tropes of the investigation into the criminal underworld with a brightly lit, neon-hued, and brilliantly stylized hard lean into New Black Cinema technique.

The 1990s heralded what would become something of the apex of neo-noir. With both commercially successful and critically acclaimed films of the 1980s suggesting paths for reinvigorating and reimaging the dark themes, stylized chiaroscuro, and archetypal characters of film noir, neo-noir blossomed during the decade. Steamy erotic thrillers, dark rural mysteries, horror-inspired investigations, twisted romances, action thrillers, urban crime dramas and more took the raw themes and tropes of film noir and made them new again: their presence was so ubiquitous and notable it was covered even in Newsweek.

In a parallel-but-perhaps-with-the-benefit-of-hindsight-related development, following the critical and commercial success of Spike Lee’s first films and John Singleton’s Boyz n the Hood, studio execs were open to hiring young (and some less young) black directors to helm films featuring black characters, casts, crews, and themes. Many of those “‘hood” films leaned hard into a quickly-congealing formula of urban settings, gangland rivalries, hip-hop soundtracks, drug running, and crises of young black masculinity: Menace II Society, South Central, Juice, New Jack City, Friday, and others among them. But they were also criticized and parodied (if you remember Don’t Be a Menace to South Central While Drinking Your Juice in the Hood).

For the first time in history, major studios were entrusting—albeit with deep reservations and tight control—product to a more diverse set of filmmakers. The movement didn’t last long, but it made for some exciting, heart-thumping, pulse-pounding moviemaking. And while none of these films expressed the nostalgia of say, a Body Heat, for transgressive sexual passions, some of those hood films shared much with neo-noir: their protagonists investigated crimes, fell into criminal underworlds, tentatively navigated treacherous urban labyrinths, confronted mysterious femme fatales, questioned their moral values, and found themselves shaken by the corruption they encountered.

Lee and Singleton’s successes, with their hip-hop soundtracks, inventive camerawork, and daring technique, influenced the risks Mario Van Peebles, F. Gary Gray, Ernest Dickerson, the Hughes Brothers, and others took to their streets. Carl Franklin, meanwhile, looked instead to the past for his retro-inspired film noir Devil with a Blue Dress, with its traditionalist score, stately pacing, and sepia-toned cinematography, but by and large the cultural moment was a contemporary one in both setting and style.

Duke’s Deep Cover is something of an overlooked jewel in this spate of early 1990s African American neo-noir films. Yet its origins are as white as can one can imagine—as white, essentially, as classic film noir. In the wake of their successful Internal Affairs, screenwriter Henry Bean and producer Pierre David assigned Michael Tolkin (The Player) to adapt former DEA agent Michael Levine’s exposé of failed 1980s undercover operations involving Latin American drug trafficking and political cronyism. As projected, then, Deep Cover was not only developed, produced, written by, and adapted from the work of white men, it featured a white protagonist based on Levine’s experience. Only later, according to the L.A. Times, did former Paramount production executive Gary Lucchesi, impressed with the work of Spike Lee, suggest changing the lead to a black man, even if the intent was to appeal to “niche-market” audiences.

Producer Bean was amenable to the change and soon hired Bill Duke, known at the time and perhaps still today more as a film and television character actor, to direct. Duke was directing just his third film (after 1984’s made-for-television Cannes-nominated The Killing Floor and 1991’s Rage in Harlem). While acting on Car Wash, American Gigolo, and dozens of television shows, Duke came to know actors and acting well. His was an unlikely, difficult rise through the ranks from television’s Knots Landing, where his first assignment was earned only through a clerical error but his output was strong enough to keep him behind the camera there for six years.

Duke also directed episodes of Hill Street Blues, Cagney & Lacey, and the mega-hit Dallas—though his stint there began with a racial profiling incident on his first day on the lot. Dressed in suit jacket and tie, Duke was met by the lot guard on gate duty who asked what he was delivering and to whom. Biting his tongue, Duke recalls replying he was “delivering my talent as director to the set of Dallas.” His autobiography Bill Duke: My 40-Year Career on Screen and Behind the Camera recounts this and other racist incidents and taunts suffered over his career as well as his steadfast determination to persevere in the face of systemic racism and individual prejudice.

Perhaps that experience informed Deep Cover. Its narrative does not take long to feature an ugly incident of casual racism embedded in institutional structure. Laurence Fishburne’s Russell Stevens Jr. grows up vowing to avoid the life of crime and drugs that got his father shot and killed in a liquor-store robbery. A young police officer, he is recruited by DEA Special Agent Gerald Carver (Charles Martin Smith) to go undercover in Los Angeles, who tells Stevens his criminal character will benefit his deep cover. Carver’s test of applicants for the position consists of his asking each man, all of them black, “What’s the difference between a black man and a n*gger?”

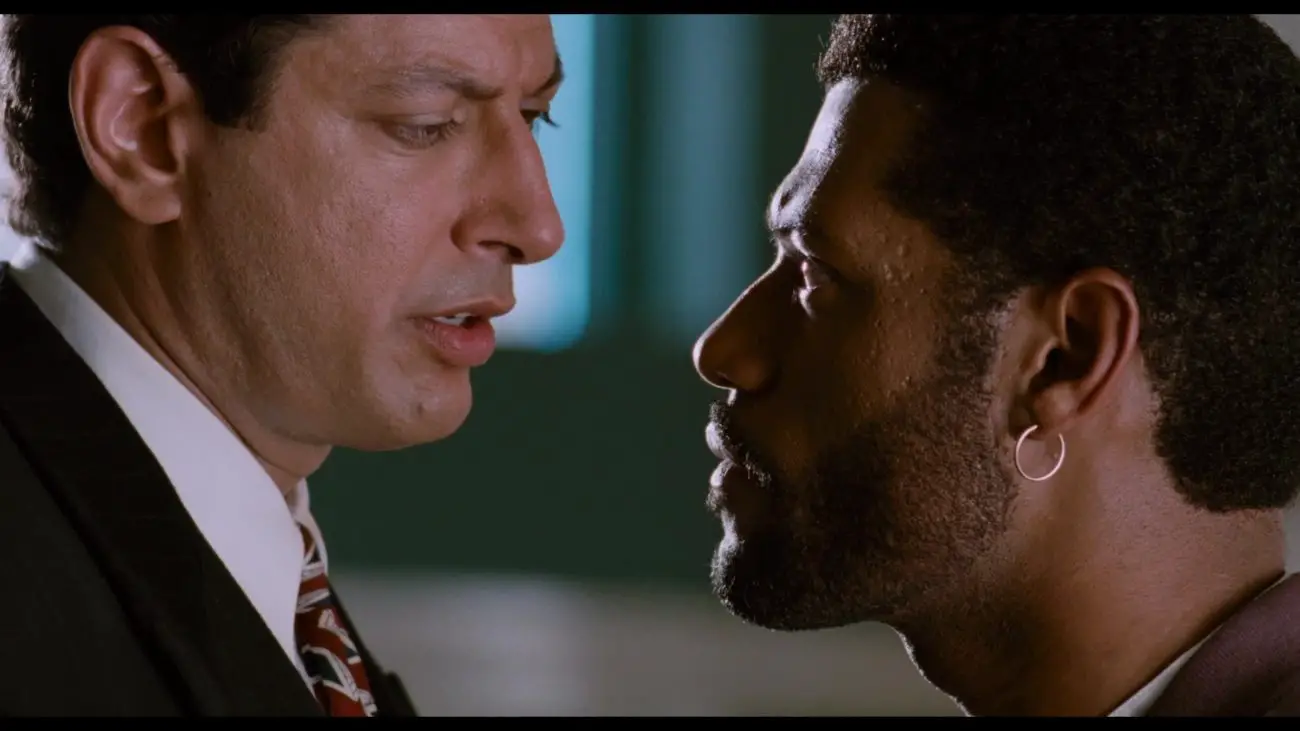

Those racist words will come back, ultimately, to discredit Carver, but the question remains central to Deep Cover‘s narrative and John Stevens’ identity. Stevens passes the test. He adopts the identity “John Hull” and begins his stealthy infiltration of the Gallegos drug empire by scoring a deal with Eddie (Roger Guenveur Smith) that goes wrong. After his arrest, arraignment, and dismissal, Stevens learns his attorney David Jason (Jeff Goldblum) is a midlevel trafficker in Gallegos’s network. From there, Stevens must climb the ladder from its lowest rung to its highest to bring down its kingpins, but at each turn he faces greater temptation to succumb to the kinds of violence and addiction his father did.

The plot, then, as scripted by Tolkin and Bean, is garden-variety investigative fare, tweaked to an archetypal hero’s-journey structure. Stevens/Hull leaves home for an adventure related to his identity, finds various guides, mentors, princesses, experiences duplicity and defeat, and finds himself in the belly of the beast, but is ultimately victorious in a decisive crisis, and emerges transformed and with a key that promises to enact change. That template is made more interesting by Stevens’ backstory and moral code. Having witnessed, in a handsomely shot and deeply troubling opening sequence, his own father’s killing, Stevens makes for an unusual protagonist: while the investigative narrative is a commonplace trope, rarely is its detective depicted directly as a child or as a man whose moral code is so explicitly articulated as is Stevens’s.

Channeling the tropes and techniques of films noir past and present, first-person voice-over narration provides a self-reflective perspective Fishburne’s expressionless face typically does not. At his lowest moment, having succumbed to the drugs he’d promised his dying father he’d never use, Stevens/Hull muses, in voice-over: “The jungle creed says the strongest feed / on any prey that it can / And I was branded beast at every feast / before I ever became a man.” This bit of Donald Goines’ street poetry articulates perfectly Stevens/Hull’s quest to become a man in a jungle of dealers, criminals, and predatory adversaries. It’s hard to imagine that the inspiration to cite those lines came from Tolkin or Bean, or for that matter, the agent Levine whose story informed the script; instead, the lines feels absolutely central to the blackness of Stevens/Hull’s experience.

Fishburne’s impressively impassive gaze elsewhere serves Duke’s purposes well. By this point in his career, Fishburne could command the screen with an intense, unwavering gravitas suggesting still a simmering of emotions behind his dark eyes and furrowed brow. Others were considered for the role, including Denzel Washington, who turned it down, and Wesley Snipes, but Fishburne, less classically handsome, less frequently cast as the romantic or heroic ideal, and a little closer to the everyman antihero commonplace to the noir-inspired narrative, makes it his own.

The degree to which any viewer finds Deep Cover persuasive may rest more than anything else on one’s willingness to accept Jeff Goldblum as mid-level drug dealer whose cover is a successful defense attorney with an absurdly white upper-class home, beautiful blond wife, and charming child—not to mention a black mistress on the side. Goldblum’s assortment of tics and quirks marks nearly every one of his roles since he stole his first scene as a street thug in the original Death Wish, and here twenty years into his career his performances are still exercises in manners, not methods. But the contrast between his snarky, twitchy David Jason and Fishburne’s resolute Stevens/Hull makes for the kind of contrastive homosocial masculine bonding and mutual distrust inherent to such narratives.

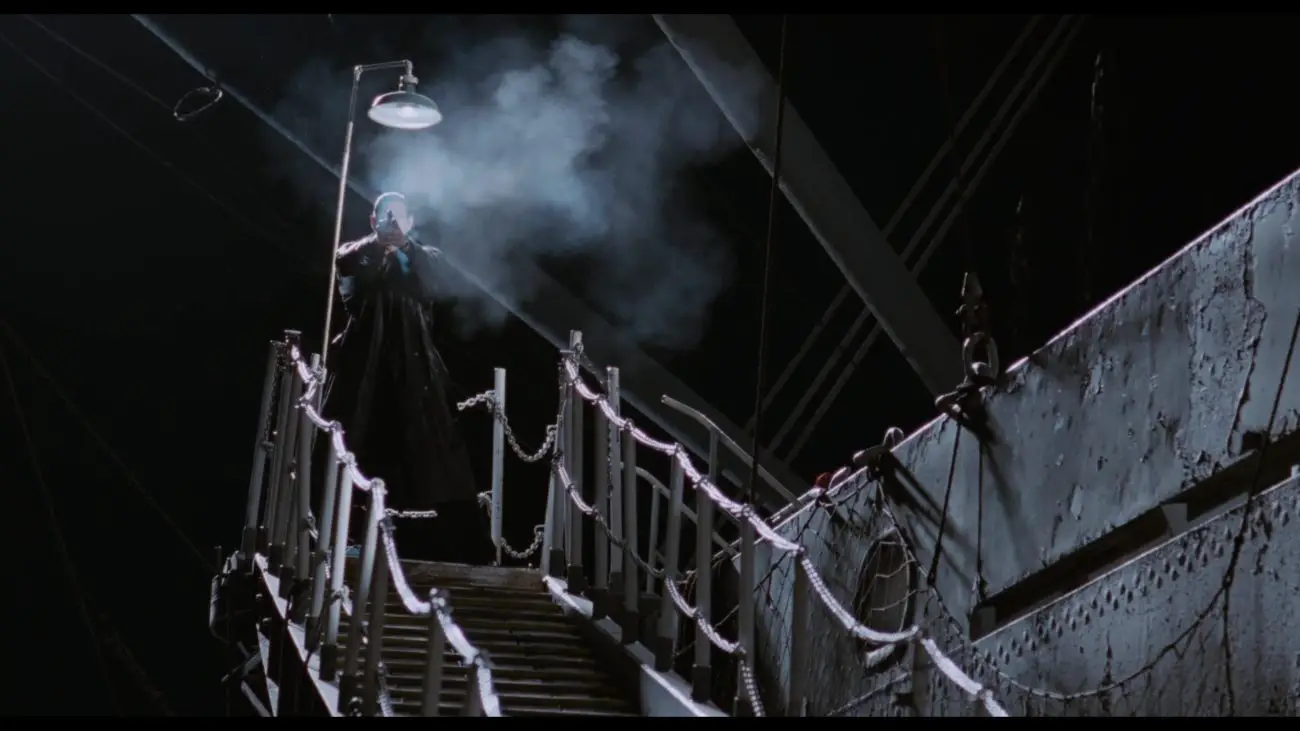

While its narrative of redemption and reclamation of black masculine identity is what makes Deep Cover an especially thoughtful narrative, Duke’s direction here is full of energy and color. His television work was largely pedestrian in terms of output, but it taught and earned him the trust of actors (as did his own considerable on-camera work in dozens of film and television episodes). Duke’s direction and Bojan Bazelli’s cinematography lean hard into the stylized tropes of film noir: its expressionist sets, rain-soaked streets, chiaroscuro effects, and canted angles.

But Deep Cover’s color scheme is even more expressionist than most neo-noir films, which often, like in say Chinatown or Devil in a Blue Dress, treat the past with a gauzy, sepia-toned reverence. Here, the lighting in exterior and interior scenes alike often amplifies the cool hues of neons. From the streets to the clubs, Stevens/Hull is lit by bright fluorescent blues, purples, and pinks. Like neon-noirs from Tokyo Drifter to Drive, Deep Cover updates the urban environment to the modern city with contemporaneous music and bold neon color and lighting for its visual scheme.

John Carter’s editing employs a wide and lively array of energetic techniques and transitions. The very first images are shot in a jump-cut style as the opening credits roll over images of drug use. Later scenes—Stevens/Hull’s first foray into the streets of L.A. makes for an especially engaging example—cross-cut between jump-cut interludes of Hull on the street, his marks, their deals, Carver in his office, and Clarence Williams III’s reverend/officer Taft surveilling, all set to the steady hip-hop thump of an instrumental cut of Jewell’s “Love or Lust” (the film’s credits, by the way, mistakenly and comically list “Jewel” (with one “L”) as the performer, though the Alaskan folk-rocker was still in her barista-and-busking days at the time and it’s pretty hard to imagine “Pieces of You” alongside Snoop Dogg and Dr. Dre). Carter uses the jump cuts elsewhere alongside a natty array of dissolves and wipes, some of them cut to a transitional figure, that lend the film much of its distinct energy.

So does the musical score throughout. Jewell (not Jewel!), Paradise, Kokane, Calloway, Shabba Ranks and Chevelle Franklyn contribute cuts to Michael Colombier’s score, but the end credits hit loudest, with Dr. Dre and Snoop Doggy Dogg (as he was then credited) collaborating on the titular track. “Deep Cover” was Dre’s first solo-credited release (after the breakup of N.W.A.) and the first appearance on a record by Snoop Dogg, more than a full year before his debut album Doggystyle took G-Funk to the mainstream by debuting at No. 1 on the Billboard 200.

In an era when boomboxes were still the currency of hip-hop culture, “Deep Cover” was a revelation, Dogg’s countryish drawl narrating the protagonist’s paranoia as he goes undercover, channeling a Dirty-Harry style thirst for vigilantism all the while repeating the “187” refrain over a thundering bass and drum. “Yeah, and you don’t stop / ‘Cause it’s 1-8-7 on a undercover cop.” The California Penal Code for murder, 187 became a trope common to 1990s rap and hip-hop and to some, a call to violence. Unlike “Cop Killer” or “F*ck the Police,” “Deep Cover” calls attention to policing street violence and the criminalization of youth behavior without the same direct call to action. (It also makes less than perfect sense as the two rappers divide the roles of undercover cop and target, but who’s to nitpick?)

Far more than just another entry in a slew of crime-focused hood films or another fashionable ’90s neo-noir, Deep Cover brought together the impressive talents of Dre and Snoop alongside Duke’s thoughtful direction and Fishburne’s steely performance: the result was a thoughtful meditation on what it takes for a young black man to transcend his origins, resist temptations, and accomplish objectives in the face of institutional racism. It was a struggle Duke knew well.

Even at the time of the film’s release, the director knew what was at stake. The L.A. Times quoted him on the importance of black-directed films’ box-office success: “I think it’s essential to get beyond the present focus on black films per se because it makes the cost of failure too high for us,” said Duke. “A flop by me or Robert Townsend or Charles Burnett or Ernest Dickerson is not perceived by the industry in the same way as a flop by a white filmmaker, like Scorsese, in terms of getting another chance at it. That window of opportunity for black filmmakers can shut just as fast as it was opened if we become the flavor of the month.”

Deep Cover was not a hit. It pulled in a serviceable $16m at the domestic box office, and that window Duke mentioned would again, for the most part, start to close just as it had before the successes of Lee and Singleton, at least until very recently. Duke would continue to direct a handful of films over the decade, but by and large the studios’ interest in black filmmakers’ stories would wane. Deep Cover may be nearly 30 years old, but its relevance is not limited to its neon-noir expressionism. It also exposes the façade of an integrated and justice-minded DEA as something inherently racist and corrupt.

Decades later, as recent events have shown, those forces may be more integrated, yet not necessarily less racist. Bill Duke’s Deep Cover told us what we needed to know, and did so with panache, skill, and prescience.

If you take the skin color element out of it, it becomes a story of good vs evil and how the two sides get muddled in the real world.

Sounds a little like the original script Tolkin and Levine were developing before Luchessi intervened and hired Duke! Glad they went in the direction they did.

Thanks again for reading Film Obsessive!