It’s hard to imagine that writer-director Seth A Smith’s creepily claustrophobic sci-fi horror drama Tin Can was written and filmed before the COVID-19 pandemic. So uncannily prescient is its script—co-written by Darcy Spidle—in anticipating the conflicts coronavirus unleashed that Tin Can seems almost a direct comment on our current condition.

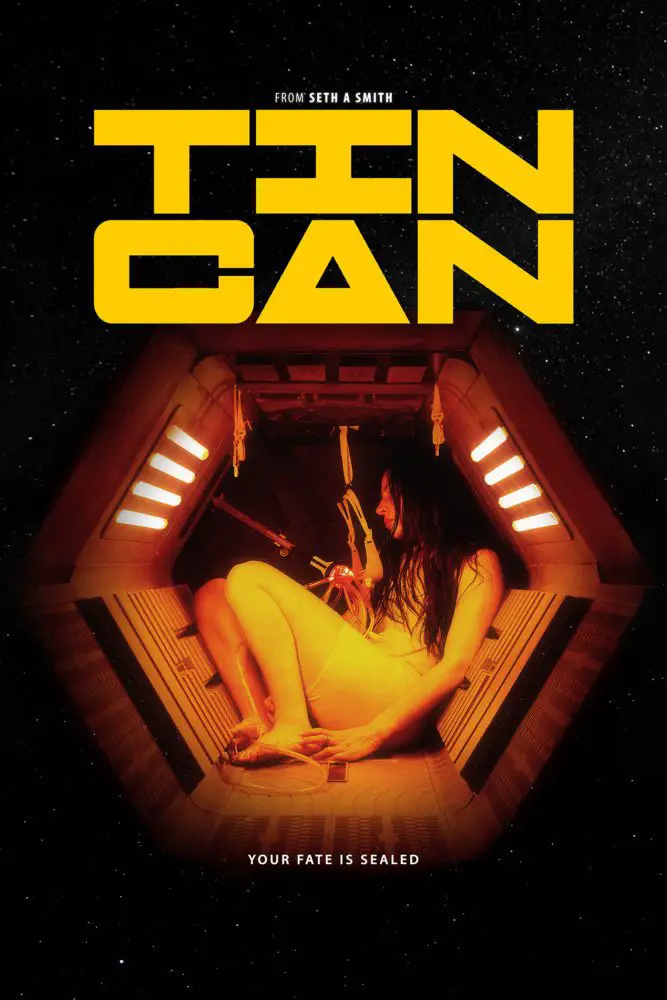

Curiously, Tin Can was not planned as such. But it presents willing, patient viewers with the very best kind of thought-provoking science fiction hybrid with Cronenbergian body-horror tropes in a uniquely cinematic visual design. The film restricts itself for the entirety of its first half to a small metal chamber where its protagonist finds herself imprisoned. And in doing so, it relies on an impressive visual conceit, effective sound design, and a first-rate performance from Anna Hopkins.

A brief precis sets the stage: Hopkins plays Fret, a research parasitologist working in a laboratory, hoping to find a cure for a fungal infection that has become pandemic. The fungus, dubbed “Coral,” grows to hard shell before consuming the body. At the “Vault” where Fret works to find a cure, the diseased—including her ex-husband John (Simon Mutabazi)—are quarantined. Meanwhile, the rich overseers invest simultaneously in a hush-hush technology that might preserve themselves in stasis pods until a cure is found.

Just as John’s disease advances to the point where his only hope is to be preserved in one of these pods, Fret makes a breakthrough. But before she can share her discovery, she’s knocked unconscious—and ensconced herself in one of these mysterious pods. Tubes and sensors are attached to her mouth, nose, and eyes, every orifice it seems except her ears, which allow her to hear John’s voice in a nearby pod. Her feet sit in viscous goo with a mysterious translucent tissue floating about.

Desperate to know how and why she was captured and imprisoned, Fret’s analytical, problem-solving mind takes charge, methodically disassembling the cell’s apparatus, discerning its purpose, and plotting her escape. With nearly this entire first half of the film set inside a literal “tin can,” Hopkins’ acting talents are similarly put to the test, and the performance is excellent. Hopkins brings Fret’s intelligence, resolve, and tenacity to life with her emotive expressions, limited gestures, and sparse dialogue.

The set design is Spartan too, but highly effective. Smith limits viewers’ perspective, largely, to Anna’s, or to our looking at Anna from less than a meter away. The set and props are low-tech but highly effective at creating a mysterious, plausible, and repulsive tomb; meanwhile, the evocative effects create an immersive, claustrophobic experience. Tin Can is a film probably best seen in total darkness and on a large projection screen, where its small set will have the opportunity to immerse and overwhelm a viewer; it’s certainly not made for watching on your iPhone.

The questions confronting Anna are many: Who put her there? And why? (She certainly didn’t pay for the privilege.) Did her enslaver know of her breakthrough cure? How, and why, was her ex-husband entrapped? What is the endgame of those who have imprisoned her? And how, ultimately, can she find her escape—and, hopefully, bring her potential cure to the benefit of all humanity?

The second half of Tin Can takes place largely outside the can itself but is nearly as limited in its setting and every bit as persuasive in its design. When fungus and metal fuse with the human form, the consequences are even more nightmarish: despite what I assume is a smallish budget and limited effects, the design of this whole sequence is oppressively brutalist, almost as if the Giacometti-like wraiths of Phil Tippett’s Mad God came to life in the form of armored sentries silently, slavishly fulfilling their predestined duties. The environment itself becomes a Steampunkish organism.

What I admire so much about Tin Can is its inventiveness in creating plausible, memorable, uniquely visceral environments from the simplest of cinematic techniques: close-ups, Foley sounds, practical visual effects, and the like. A film need not be laden in CGI to create a unique and expressive environment: this, Mad God, and After Blue (Dirty Paradise) all this year demonstrate that very fact.

Our collective humanity’s attempts to contain COVID-19 have illustrated that a pandemic is far more than the viral transmission of exhaled particles of infectious respiratory fluids; it’s the ways in which our response to that transmission exhibits our most human of frailties: our egos, jealousies, anxieties, prejudices, and beliefs become barriers to the disease’s eradication.

That’s a point Tin Can makes, and unambiguously so. What’s surprising is that Smith shot the film in 2019, the year prior to COVID-19’s pandemic status. How could he have been so prescient as to direct a film with so many ramifications and implications for what would happen just a year later? His pandemic is more visceral and visual, with tooth- or bone-like growths consuming its victims’ bodies, but it’s no less deadly and no less dividing than the coronavirus has been. While I’m sure no filmmaker wants their work delayed for any reason, Smith’s Tin Can is just now slated for theatrical release and—given our protracted, conflicted response to the recent pandemic—more timely and potentially impactful than ever.

Tin Can opens in theatres August 5 and on VOD August 9, with home video release scheduled for September 6.