What is identity and how it is formed? Does it change or does it stay the same throughout our lives? How much of human identity is linked with the face? How can social interactions and the roles we play in society influence it? These are some of the questions raised by The Face of Another, a 1966 film made by Hiroshi Teshigahara based on the novel by Kōbō Abe.

The Face of Another tells the story of Mr. Okuyama (played by Tatsuya Nakadai), whose face has been damaged as a result of an accident at his workplace. The scars are so repulsive and frightening to other people that he chooses to wear bandages to hide them. The loss of face has a dramatic effect on his life, changing every aspect of it, including his relationship with his wife, and most importantly his perception of himself. Eventually, he finds a doctor who replaces damaged parts of his patients’ bodies with very naturalistic prosthetics. The doctor, however—a psychiatrist to be more specific—states that he does not treat those damaged parts of the body but fills the gaps in the mind. He creates a mask for Okuyama.

Mr. Okuyama—Living without a Face

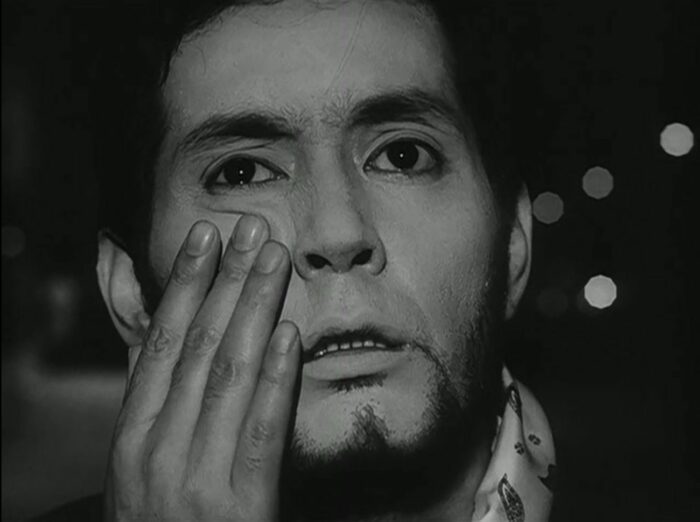

The first time we see Mr. Okuyama is a close-up X-ray moving image while he’s telling the doctor about the accident. We are shown his skull because he simply has no face. And it’s not only physical damage. What makes Okuyama’s situation almost unbearable is that he feels alone in it. He feels that others don’t even seem to remember the accident and act like it hasn’t happened. But at the same time, he has to wear bandages so to avoid gazes from shocked people, and perhaps to avoid the disturbing thought that he has become a monster.

Initially, he tries to convince himself that the face is not the most important thing, that the soul, the foundation of his identity is intact. But with time, he realizes that it’s not that simple. The face is not just a layer of the skin above the neck. It’s the means of communication with people, society, and through this—the means of communication with himself. So, with losing a face, a person can lose all contact with the outer world and contact with himself, eventually. As he says:

The face is the door to the mind. Without it, the mind is shut off. There‘s no communication. The mind’s left to corrode, to disintegrate.

Okuyama’s communication with the outer world worsens, which includes even that with the closest people, like his wife. The crucial factor leading him to decide on making a mask is his wife’s rejection.

Just before making the mask, Okuyama arranges a different life for it. He tells his wife that he’s going on a business trip and rents two apartments: one for himself and another for the mask. From now on, he will lead a double life. Not for a long time though.

The Face as a Part of Social Interaction

Okuyama’s main focus after creating the mask becomes to seduce his wife. Thus he creates a strange love triangle with himself, his wife, and the mask. What he does not anticipate in this game is that his wife sees through it. She is, in fact, one of two people who are not fooled by his mask. The other one is an intellectually disabled girl, the daughter of his apartment’s superintendent. This is not surprising if we consider a face an integral part of social interplay. That would mean that face is something that is meaningful for those for whom social roles matter. This girl just doesn’t pay attention to it.

The same would be true for Okuyama’s wife as her relationship with her husband entails stripping all the masks off of each other. ‘In love, we all try to unmask one another’, she tells her husband after his failed attempt at seduction as the mask.

This remark continues the earlier conversation between them about using make-up as a mask. According to Okuyama’s wife, in older times hiding a face with make-up by women was a sign of humility. But on my part, I would add it also hides vulnerability. Only women are always aware of the ‘masks’ they are wearing and they do not try to hide the fact. And it’s the most important point here. You must not for a moment believe that it is real and identify with the mask. It’s not surprising that the wife saw through the mask but continued the game anyway because she thought it was a masquerade for both of them. But Okuyama was not playing. Instead, he began to identify with his mask.

Creation of Artificial Identity

Creating a mask for Okuyama is an experiment for the doctor, as it’s the first time when he replaces a whole face. Replacing a finger, hand, ear or other parts of the body would fill the gap in the soul of a patient. But replacing the face is a different level, as it affects the whole identity. So, doctor also warns Okuyama to be careful with the mask because it can change him. He understands the danger it may entail:

Masks can utterly destroy all human morality. Name, position, occupation… all such labels wouldn’t matter anymore. Everyone would be strangers to each other. It’d be natural to be alone. There’d be no need to feel guilty about it.

The doctor’s office is worthy of special mention. It’s a surreal place full of artificial body parts and transparent screens with drawings like Langer lines or Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man. A modenr Dr. Frankenstein might have an office like this. This doctor also creates a living thing from non-living. The rubber mask put on the living man’s face gradually becomes alive. He says they are interfering with natural laws, and indeed his cabinet looks like a place where artificial human beings could be created… if the experiment with Okuyama proves successful:

I can mass produce them. A face, easily taken off. A world without family, friends, or enemies. There’ll be no crimes because there’ll be no criminals, no one will want freedom because we’ll all be free, no one will run away because there’ll be no place to run from. Loneliness and friendship will be one. There’ll be no need for trust among people. There’ll be no suspicions or betrayals.

It sounds like a nightmare, a dreadful place to live indeed. But he adds: ‘a world like that can’t exist.’ Although we take a glimpse of that possibility at the end of the film. Suddenly, the doctor and Okuyama find themselves among the crowd of faceless people. It’s how the doctor sees them, but it’s also how they are—the crowd of lonely people.

The Destruction of Identity

The loneliness of Okuyama in his trouble connects him to a storyline of a beautiful young woman whose face is disfigured on one side. This story is actually a film that Okuyama saw and told his wife. The girl is apparently a victim of Nagasaki bombing. She is no less alone than Okuyama, being perceived as a monster by kids, young men backing away as soon as they see her scars. Just like Okuyama thinks that it would be easier for him if his condition were the result of war, the girl also thinks that war could save her. The only people who accept her are other victims of war—patients at the mental health facility, former military men who, in their minds, continue living in the war. And there is also her brother who tries to accompany her in her loneliness.

This storyline, which is shown in parallel with Okuyama’s relationship with his wife, demonstrates the contrast between the girl’s attitude to her loneliness and Okuyama’s to his. The damage is the same, both of them are deeply lonely. But the decisions they make because of this, are radically different. The girl eventually eliminates herself from the picture physically, while Okuyama eliminates his soul and cuts the connections with the world.

Echoes of the War

There is one theme in the film which is not exclusively connected to the topic of identity, but its presence is palpable throughout the film. It’s the theme of war, namely World War II. The girl’s story also refers to this theme through her own background and the patients at the mental hospital; also the scene of attempted abuse of the girl by one of the mentally ill patients where Hitler’s speech can be heard mixed with the disturbing sounds of Toru Takemitsu’s soundtrack. Another reference to the war and its influence is the restaurant where Okuyama and the psychiatrist go—München—with its western style, beer, and a singer who sings Takemitsu’s German-language waltz.

I would say that it’s a hint to the repressive and damaging influence of the war, the influence that causes the emptiness in the souls of people. It creates perhaps the closest thing to the world the psychiatrist was describing—it’s the symbolic example of ‘mass production’ of the masks.

The Life of the Mask

The central scene of the film is where the psychiatrist puts the mask on Okuyama’s face for the first time. At first, Okuyama doesn’t feel the mask to be a part of him. But the psychiatrist assures him that it will gradually, and gives him an injection of sedative so that Okuyama could relax. This is needed to avoid uneven wrinkles. However, it looks like its purpose is also to let Okuyama accept the mask or, in other words, surrender to it. The way this part of the dialogue between the doctor and Okuyama is filmed is interesting in terms of showing power dynamics. The camera tilts and shows the psychiatrist bending over Okuyama who keeps insisting on being himself, but the drug takes effect and he stops resisting.

This dynamic is reversed in the last scene where Okuyama, already acting as a mask, kills the psychiatrist. The smile that the doctor has taught him in order to look more natural is now reflected back. The doctor receives the smile just before his ‘creation’ stabs him in the back. The mask kills its creator to reclaim freedom. Now Okuyama is no one, and he also knows that he’s not the only one who is lonely. The psychiatrist tells him:

Freedom is always a lonely thing. Some masks come off some don’t.

The last shot clearly suggests that Okuyama’s mask won’t come off anymore.

The Masks We Wear

We all wear many different masks throughout our lives. It’s a part of being human and living in society. But the danger awaits when we ignore the thin line between ourselves and the mask. The danger is identification with our masks. It can bring imaginary freedom, but what we are free from is, in fact, our identity, and morality.

The society described by the psychiatrist is grim, though uncannily easy to imagine. But why does he claim that it can’t exist? Well, here’s my take: in that world, we would be able to do whatever we want. But what can we want if we have no identity? The roles we play are only useful to the extent that it serves our core identity, making possible for it to connect with others. Only this way we can be a part of society. And only this way society can exist because it relies on these connections between individuals.

Thank you for the explanation. I have just watched the movie but couldn’t grasp the ideas straightaway. So this helped a lot! Thanks

Well said. Nothing better then these classic Japanese films. Thought provoking twinged with sadness. Yet highly intelligent. Bravo…