Between the ’50s and the ’70s, Japanese Cinema was at its finest. The already established legends, such as Akira Kurosawa and Yasujirō Ozu, were crafting their masterpieces while the Japanese New Wave artists, like Seijun Suzuki, Nagisa Oshima, and Shohei Imamura, to name a few, were providing subversive and controversial films to an unwitting public. Japan appeared to be the hip alternative to Hollywood and both domestic and international audiences were along for the ride.

But sometime in the ’80s, the magic was gone. Studios began to fall apart and the grandeur of filmmaking seemed to disappear, with endless direct-to-video releases and B-movie fare flooding the market place. The big-name directors were either dead, dying, or producing epics elsewhere in the world. But before the prophecized “end” of cinema came to Japan (as is often prophesized here in the United States as well), a number of unique new artists—as well as less popular but established names from the past—began to forge a path for what would be an international renaissance in the ’90s.

There would not be a “Beat” Takeshi Kitano, director of game-changers like Violent Cop (1989), Sonatine (1993), and Hana-Bi (1997), without director Juzo Itami’s unique approach to comedy and the ever-evolving Yakuza lifestyle. There wouldn’t be a Takashi Miike, director of notable shock fests like Audition (1999), Dead Or Alive (1999), and Ichi the Killer (2001), without Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s full, serious embrace of genre conventions. While Kitano and Miike would become more popular and impactful, the influential work in the previously viewed “genre” fare (such as crime/yakuza and horror) from Itami and Kurosawa, amongst others, would allow for the birth of a more accepting and serious take on those types of projects.

That isn’t to say Japan didn’t embrace its living legends. While Kurosawa still had prestige pictures being produced in the ’80s (most specifically Ran, which we’ll look at), new generations of filmmakers, like Hirokazi Kore-eda, would channel their inner Ozu and provide deeply complex family dramas that played with morality and love in the ’00s.

The Criterion Channel has been a champion of Japanese cinema overall, making virtually the entire catalogs of certain directors available for mass consumption. However, it seems the service also has a plethora of films from these lesser-known, but still important, directors from an era in Japanese film not often given respect.

While the films from the ’80s onward are in smaller quantities (and probably lesser demand), I managed to pick four films from directors that deserve the attention they likely wouldn’t get otherwise. But to also keep in touch with Japan’s past, as it went into the future or as it was re-imagined later, I also chose two films representing the passing of the torch from the old to the young.

Fall Guy (1982)

Director: Kinji Fukasaku

Story: Ginshiro (Morio Kazama) is a handsome movie star suddenly contending for close-ups with rival actors, leading to grand histrionics that ruin shots and cause production delays of his latest samurai epic. Ginshiro’s sycophantic entourage, including the obsessively loyal Yasu (Mitsuru Hirata), enable his behavior and will do just about anything for the childish and vain actor.

Sensing his star fading, and to avoid falling out of favor with the public, Ginshiro tasks Yasu to marry his pregnant girlfriend, actress Konatsu (Keiko Matsuzaka), to avoid unwanted publicity and scandal. Already in love with Konatsu from the first time he saw her on screen, and always willing to do Ginshiro’s bidding, Yasu agrees and tries to make Konatsu as comfortable as possible, taking on dangerous stunt work to provide extra money for their “marriage”. The problem: Konatsu and Yasu have a real connection and the jealous Gin-Chan may have more use for Yasu as one of the grandest stunts in Japanese film history is in need of a “fall guy”.

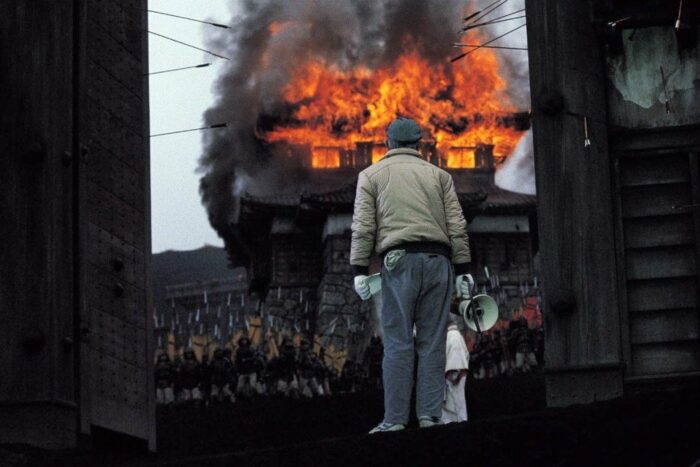

Thoughts and Analysis: I’m hard-pressed to find a satire more cynical and nihilistic than Fall Guy, whose basic premise is of a sycophant so loyal to his atrociously narcissistic movie star pal that he is not only willing to marry said star’s clearly abused pregnant girlfriend but also take the most ludicrous and dangerous stunt fall in Japanese film history (down that stairway you see in the picture above) all in the name of loyalty. Fall Guy makes it clear: you will die for not only a celebrity but for the concept of celebrity itself.

And the fact that something this biting about celebrity culture came out decades before the reality TV craze and the YouTube era is shocking to me. Fall Guy might as well have been made in 2019 with its exquisite prophecy. Everything from the short window of eligibility for “attractive” female leads, the glorification of Entourage group think, the magnification of the “there are no small parts, only small actors” lifestyle, and the “I’ll-do-anything” approach to getting attention that blankets many of the world’s cultures right now is tackled with scalding accuracy. Fall Guy might be one of the most realistic depictions of the inner workings of Hollywood that isn’t actually about Hollywood. We should have seen it as Japan’s portent to the world of entertainment.

If You Want More Fukasaku: Fall Guy is the only film of Fukasaku’s available streaming on Criterion. However, the prolific director, who was directing movies from 1961 until his death in 2003, has plenty of notable films under his belt. Arguably his most popular work is Battle Royale (2000), a pre-Hunger Games cult classic involving school kids being forced to hunt and kill each other. He also co-directed the sequel, Battle Royale II (2003), but died during filming. Also of note, Fukasaku co-directed the Japanese portions of Tora! Tora! Tora! (1970) while his sci-fi film The Green Slime (1968) was the first “cheesy movie” to get the Mystery Science Theater 3000 treatment.

Availability: Fall Guy is available exclusively on the Criterion Channel. It has not been assigned a spine # or a DVD/Blu-Ray release.

Ran (1985)

Director: Akira Kurosawa

Story: In this adaptation of William Shakespeare’s King Lear, the setting changes to the Sengoku period of Japan, where ruling warlord Hidetora Ichimonji (Tatsuya Nakadai) decides to concede power and retire, allowing his three sons to rule his castles in his place. Overall power is given to Jiro, the eldest son (Jinpachi Nezu), with second-born Taro (Akira Terao) next in line.

While Jiro and Taro worship Hidetora’s every word, third son Saburo (Daisuke Ryu) gives his father truthful observations and harsh criticism, warning that Jiro and Taro only fake their loyalty. Feeling disrespected, Hidetora banishes Saburo and his loyalist advisor, Tango (Masayuki Yui) and moves forward with his plan. Before long, Saburo’s proclamations come true as Jiro, led by his ruthless wife Lady Kaede (Mieko Harada), begins to unravel the House Ichimonji by waging wars and engaging in betrayals, including the banishment of Hidetora himself (which leads to his madness and an uncomfortable personal journey through hell).

“Men prefer sorrow over joy… suffering over peace!”

Thoughts and Analysis: Ran is often touted as a masterpiece and, well, most of Kurosawa’s films are eligible for that honor. Ran doesn’t totally click with me and I’m sure I’m in the minority. But despite some of the failings I found, I think Ran undoubtedly excels in the areas that Kurosawa is at his best: personal, small moments of reflection. Kurosawa certainly can show a lot, but I prefer it when he lets his actors tell.

Ran is a sprawling epic, made with what was, at the time, the biggest budget in Japanese film history (keep in mind, this was the ’80s, when Japanese studios were struggling or going away for good). And while I think Kurosawa is a master filmmaker, I found the large battle scenes confusing and illogical. Also, the scope seemed unnecessary as King Lear’s themes are best served, as they’ve been for centuries, on a stage. It is an actor’s play, not one of atmosphere and environment. And when Kurosawa plays with the environment, it comes off as rather stilted.

But with such powerhouse actors as Nakadai (as Lear stand-in Hidetora) and scene-stealer Harada (as the venomous Lady Kaede, who is breathtaking to watch), never has a Shakespearean adaptation, English, American, or otherwise, conveyed the absolute folly of war and the meaninglessness of death. And most of that is most effective in those small moments between actors, not in a gruesome battle scene with hundreds of horses and endless arrows in the sky.

Ran is full of characters finding out that all they lived for was pain and suffering and that little reward comes from the loss of humanity needed to achieve domination; to win. The dead look in Hidetora’s eyes as another of his sons die or the vindication in Kaede’s face when, before losing her head, she realized her long game of ending the Ichimonji empire, mostly from within, had succeeded, is all you need to get the point across: war is hell and we, as humans, have created it and, as a result, bathe in it.

If You Want More Kurosawa: I cover Kurosawa’s classic Rashomon (1950) in the first part of this series on Japanese filmmakers. I also looked at his noir masterpiece Stray Dog (1949) in the Noir portion of this series. Overall, twenty-seven Kurosawa films are available to stream on the Criterion Channel, spanning his entire career, from the ’40s to the ’90s.

Extras on Criterion for Ran: full audio commentary on the film from Kurosawa historian Stephen Prince, an interview with the late Sidney Lumet about the film, a documentary about Kurosawa directed by the late Chris Marker, called A.K. (1985), a 2005 interview with Ran actor Tatsuya Nakadai (who also played Tsune the Immovable in the film Heat Wave, covered below), and three trailers.

Availability: Besides streaming on the Criterion Channel, Ran is likely only available from third-party sellers on DVD as the Criterion edition, spine #316, is out of print.

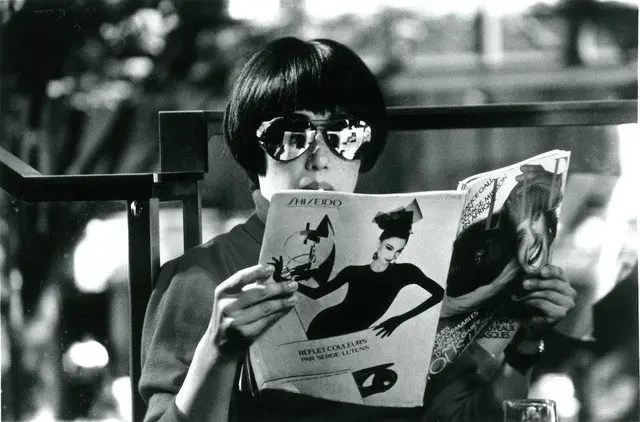

A Taxing Woman (1987)

Director: Juzo Itami

Story: As the Yakuza begin to forgo typical gang violence and engage in “legitimate” business as a way to infiltrate Japanese society, the only way the government can nail them with crimes is with tax evasion. As the crafty gangs try to launder money through increasingly complex ventures, such as love hotels, real estate firms, and bank loans, the National Tax Agency sends its sharpest minds to deconstruct the books and find the cracks in their schemes.

The most unheralded of the tax auditors is Ryōko Itakura (Nobuko Miyamoto), one of the few females in the agency, whose unconventional methods and unwavering dedication to her job has her risen in rank and favor. Her white whale is Hideki Gondō (Tsutomu Yamazaki), who runs various love hotels throughout Japan and whose accounting books are perfectly cooked to prevent evidence from sticking. Ryōko will go against city officials, politicians, crooked banks, traditionally violent yakuza gangs, and Gondō himself to uncover the damning evidence, despite the fact that she and Gondō have burgeoning respect for each other.

Thoughts and Analysis: A Taxing Woman is a strange film but in a good way. If anything, its tonal shifts can keep the viewing experience unpredictable and exciting which, in a typical gangster/yakuza movie, is very much needed. But A Taxing Woman is, to its benefit, not a typical yakuza film. Usually, you brace yourself for some ultra-violence and the typical tropes of rival gangs and conflict from within.

But A Taxing Woman does not have one scene of violence. And it doesn’t involve cops and robbers but the National Tax Agency of Tokyo, making our heroes more math nerds than action heroes. Lead actress Miyamoto shifts between slightly bumbling and awkward to Sherlock Holmesian, reaching devastating conclusions with her against-the-grain analytical thinking. Miyamoto feels more real: a workaholic prone to mistakes, if not flights of fancy. It certainly beats the typical protagonist we’d expect: the grizzled, under pressure cop with an ax to grind.

I mentioned earlier that Itami’s film led the way to see more realistic yakuza far from the likes of Takeshi Kitano. While Kitano still engaged in violence and the glorification of the anti-hero, the machinations of how he represented the yakuza was only slightly exaggerated. A Taxing Woman shows the yakuza as they likely really are: businessmen, looking to evade the clink, but also adapt to an ever-evolving society. Not simply thugs in suits but intelligent men who need to think one step ahead of the multiple organizations on their heels.

In other words, it is refreshing to see the “bad guys” and “good guys” as three-dimensional characters with shades of grey as opposed to white hat and black hat. The titular Taxing Woman Ryōko is an excellent auditor/inspector but likely a terrible mom (at one point in the film, she berates the five-year-old she’s left at home alone over the phone for not knowing how to work a microwave) while the antagonist Gondō is a sex obsessed swindler who also happens to care deeply for his son’s future.

A Taxing Woman was an incredible success in Japan, winning nine Japanese Academy Awards, including Best Film. It’s kaleidoscopic tone (sometimes it plays as a screwball comedy, other times a melodrama, and yet others as a “police” procedural) apparently played to a wider audience. I can’t say it is a perfect film, but it is no doubt an influential one that never bores.

If You Want More Itami: Not quite as prolific as other directors on this list, Itami only directed ten feature films, nine of which starred his wife Nobuko Miyamoto (the titular Taxing Woman). All ten are available to stream on The Criterion Channel, including A Taxing Woman’s sequel, A Taxing Woman’s Return (1988). Repeatedly running afoul of the Yakuza gangs he often lampooned in his films, Itami died a mysterious death in 1997. It was declared a suicide but others take credit. From the Japanese Subculture Research Center (writer: Jake Adelstein):

It’s a dangerous thing to expose the worst of the yakuza for what they are. Itami Juzo, directed the first realistic film about the yakuza, Minbo, in 1992. Goto-gumi members attacked him for doing it, slashing his face open. He would later tell the New York Times in an interview, “They cut very slowly, they took their time. They could have killed me if they wanted to.” Eventually they did. On December 20, 1997, after a weekly magazine wrote about his extra-marital affair, he allegedly killed himself. A former member of the Goto-gumi told me in 2008, “We set it up to stage his murder as a suicide. We dragged him up to the rooftop and put a gun in his face. We gave him a choice: jump and you might live or stay and we’ll blow your face off. He jumped. He didn’t live.”

Sometimes art imitates life and vice versa.

Availability: A Taxing Woman is available exclusively on the Criterion Channel. It has not been assigned a spine # or a DVD/Blu-Ray release.

Heat Wave (1991)

Director: Hideo Gosha

Story: Rin Jyoshima (Kanako Higuchi) is a traveling gambler, renown amongst the legitimate and yakuza houses for her skill and intuition, earning the nickname of Ghost Light Rin. Orphaned at a young age after her gambler father was murdered by an unknown rival with a menacing tattoo of a Samurai on his back, Rin was taken in by the adoring Kosugi family, who raised her as their won alongside her now step-brother Ichitaro.

Twenty years after leaving the family to answer her calling as a gambler, Rin happens to bump into Ichitaro (Masahiro Motoki) who has fallen on bad times. His inn has been taken over by the ruthless Iwabune family and his debts are rising, putting his life in danger. Rin decides to enter a high stakes tournament to win Ichitaro his inn back but must face the legendary Tsune the Immovable (Tatsuya Nakadai) who, in an intriguing twist, may have been Rin’s father’s murderer.

Thoughts and Analysis: With the exception of the loud and explosive final ten minutes, a section of the film seemingly taken from another movie altogether and cut and pasted into the final assembly, Heat Wave is a masterclass of suspense, even when you have no idea what is going on.

And that is a sign of a good, if not great, director. Heat Wave is about the world of high stakes gambling, usually involving the Yakuza and their popular gambling stand-ins they hire for a percentage of the winnings. Since Heat Wave takes place in the 1920s, long before the Yakuza’s mutation to a more corporate entity post-WWII, the tension of violence is constantly in the air. Not only are the players of the game involved in their own personal dramas, but the backers are heavily involved as well, staking enormous amounts of money on the backs of mercenaries who are one bad move away from costing a criminal organization millions.

Despite having no clue how the game works (I can’t find any information on it myself, but it appears, in my best estimation, to be a mix between a pure game of chance, involving picture cards, and blackjack), Hideo Gosha direction of the scenes contain such palpable tension that I didn’t need to know the rules, only that the stakes are high. The film’s can’t-miss premise (young, on-the-rise gambler plays against her father’s killer, a gambling legend, in a high stakes card tournament) hovers like a cloud over the proceedings, as the stress of playing properly under duress, as well as defeating a life-long villain, just increases the pressure on our hero, Rin.

But with style, there must also be substance, and thankfully Heat Wave has that as well in its two acting leads. Tatsuya Nakadai (also in Ran as Hidetori) is aloof and unpredictable as legendary gambler Tsune the Immovable but the real star of the picture is the graceful Kanako Higuchi as Rin, who manages to be both elegant and rebellious, a tough set of dimensions to play effectively. You have no doubts that you want to embrace Rin but you also are scared of her power. As a result, her intoxicating screen presence keeps you glued, even when, as indicated above, the rug is pulled out from everyone and everything at the very end.

If You Want More Gosha: There are seven additional Gosha films available to stream on The Criterion Channel including five of Gosha’s more traditional samurai/sword epics, including Three Outlaw Samurai (1964) and Sword of the Beast (1965). Gosha’s final film, The Oil-Hell Murder (1992), also starring Kanako Higuchi and released just months before his death, is also available.

Availability: Heat Wave is available exclusively on the Criterion Channel. It has not been assigned a spine # or a DVD/Blu-Ray release.

Cure (1997)

Director: Kiyoshi Kurosawa

Story: A woman is found brutally murdered in a Tokyo hotel with an X carved into her neck. The murderer admits to the crime but has no memory as to why he did it. Though at first, it seems like an open and shut case for Detective Takabe (Kōji Yakusho), additional victims begin to appear throughout Tokyo, all with the same X carved into them and all with a different killer, unaware of why they did what they did.

The murderers come from all walks of life (a young schoolteacher, an older police officer, a middle-aged nurse) and have no connection to each other outside of their brief contact with an amnesiac drifter named Mamiya (Masato Hagiwara), whose question-based speech patterns and hypnotic suggestions start to get under Takabe’s skin. Dealing with a mentally ill wife at home and a serial killer situation with a rotating and random team of unwitting killers, Takabe, starting to crack after continued exposure to Mamiya, must figure out how Mamiya is involved and how he can avoid his own decaying mental state.

Thoughts and Analysis: Of all the available Japanese films in Criterion’s streaming collection between 1980 and 2019 (and there aren’t too many), none devastated me more than Cure, a psychological thriller, police procedural, and horror film all wrapped into one two-hour mental trip.

Mixing the slow burn, widescreen look of Michael Mann, in which the environment itself, from buildings and streets to even the background horizon, becomes its own character, and the psychological tension of a Thomas Harris adaptation, Cure’s ambitions are less to scare you with what you see and more to frighten you with what you think. As you piece together the puzzle of Cure, every step you take may uncover not only your own deepest, darkest secrets but, perhaps, your shameful desires. It makes putting the puzzle together both essential but also damning.

Yakusho, who has been in some major American films in the last decade, is a tour de force in Cure as he becomes our eyes and ears to a serial killer situation involving multiple killers and the specter of the supernatural. But naturally, as he begins to question his own reality, so do we. We have no one to rely on and therefore we begin to question ourselves as to what we are seeing. Hardly do any films take you on a journey so completely and that is why I consider Kurosawa’s thriller to be a true masterpiece.

If You Want More Kurosawa: Unlike most of the directors in this guide, Kurosawa is still alive and making films, his most recent release being the drama To the Ends of the Earth (2019). Kurosawa has directed a large number of horror films, including the original Pulse (2001), which (of course) had an American remake during the J-Horror craze of the mid-’00s. He works most often with Cure star Yakusho, the duo having made at least seven films together.

Extras on Criterion for Cure: Though there aren’t any extras for the film itself, there is a short documentary on the film Jigoku (aka “Hell”, 1960) called Building the Inferno (2006), which features interviews with Kurosawa.

Availability: Cure is available exclusively on the Criterion Channel. It has not been assigned a spine # or a DVD/Blu-Ray release.

Still Walking (2008)

Director: Hirokazu Kore-Eda

Story: Ryota Yokoyama (Hiroshi Abe) has recently become married to Yukari (Yui Natsukawa), a widow with a shy son named Atsushi (Shohei Tanaka). For the first time as a family, they are visiting Ryota’s parents for their annual celebration of Junpei, the eldest son of the Yokoyama’s, who died saving the life of a drowning boy over a decade earlier. In between jobs, Ryota is worried about his father Kyohei’s (Yoshio Harada) judgment. A cold and calculated doctor who feels he lost his future with Junpei, Ryota’s relationship was already on thin ice to begin with.

During the 24 hours the film takes place, we meet the Yokoyama’s matriarch Toshiko (Kirin Kiki), an impressive cook with a chilling secret, Ryota’s vapid sister Chinami (You) who brings her two loud children and goofy husband, and the never vanishing specter of Junpei who, while never appearing, is ever-present in everyone’s thoughts and expectations. It is a family gathering of simmering tensions and disappointments, but perhaps moments of hope.

Thoughts and Analysis: Kore-Eda’s films, on paper, seem like pretentious indie fluff. And despite my immediate reaction, upon reading a description of his plots, of condemning it as misplaced “important” drama, I always end up completely engaged, absorbed, and affected by how real and honest the films are.

Kore-Eda manages to tap into the dynamics of real-life that often elude filmmakers who aim for reality-based drama. Lesser directors still make it feel like a show with actors playing dress-up. But a film like Still Walking is almost voyeuristic in its documentary style, depicting naturalistic actors doing mundane things and carrying multiple conversations that don’t necessarily advance or service any plot.

And while the idea of watching ten characters cook food and discuss random topics might seem like snores-ville to many, Still Walking is so dense in its production design, to the bathroom with the cracked tiles to a dead relative’s room collecting dust, that it never feels artificial. Even stage plays, with their more purposeful artifice, still seem staged. But the home in which we spend 24 hours in during Still Walking is so lived-in and real, that you can’t help but be absorbed into it; a fly on a wall invading the privacy of a normal family.

That’s not to say Still Walking doesn’t have drama. It’s just that the drama is just as lived in as the home and comes out naturally, not artificially. And most importantly, it is never bombastic. We aren’t waiting for characters to change literally overnight or for there to be an explosion of emotion that has taken the characters years and years to realize. Because that is not how real family dynamics work. Apathy, disappointment, shame, pride…these all generate over time and not just from one event. So instead of these emotions dictating the plot, they simply hover over them, like a fog and the character’s natural responses to them lead to subtle drama.

Still Walking is never boring though its two hour run-time without much “action” may turn many off. But it isn’t often you can be placed inside the intimate confines of a family home and witness their deliberations, confessions, and awkwardness and get away with it.

If You Want More Kore-Eda: I covered Kore-Eda’s Oscar-nominated film Shoplifters (2018) here, of which he won the Palm d’Or at the 2018 Cannes Film Festival. Director of 18 feature films since 1991, Kore-Eda is a festival circuit veteran with international prize-winning films such as Like Father, Like Son (2013, winner of the Jury Prize and nominated for the Palm d’Or at the 2013 Cannes Film Festival), Nobody Knows (2004, Palm d’Or nominee and Best of Festival winner at the Santa Fe Film Festival), The Third Murder (2017, nominated for Best Film at the Venice Film Festival), and Air Doll (2009, a Gold Hugo nominee at the Chicago International Film Festival).

Extras on Criterion for Still Walking: a 2010 interview with director Kore-Eda, a 2010 interview with the film’s cinematographer Yutaka Yamazaki, and a short documentary on the making of the film.

Availability: Besides streaming on the Criterion Channel, Still Walking is available on DVD/Blu-Ray, spine #554.

I’ll be returning again at the end of this month with another a look at War films available on the Criterion Channel. If you’d like to see prior entries in my Criterion series, click on the following links: