A fascinating facet of David Lynch’s filmography is his ability to maintain the allure of Los Angeles while also shining a light on the darker aspects beneath. Looking below the exterior, in general, is a feature present in Lynch’s films, most notably in Blue Velvet by sinking his camera from the bright green grass to the red ants that live underneath. In Mulholland Drive and Lost Highway, Lynch turns that focus on Los Angeles and the promise many seek from the city. In Mulholland Drive, for instance, Betty becomes smitten with the idea of stardom after winning a dancing competition. In Lost Highway, Fred, a saxophone player, appears to be living the dream life of any musician. Nothing is as it seems with David Lynch, however, and he quickly reminds the audience of both films that there is a false promise to the embrace that Hollywood provides. There is a telling shot early in Inland Empire that begins by focusing on a sign on the side of a studio wall reading “Stage 4” accompanied by a melodic tone, suggesting a radiance to the environment within the film. This radiance, of course, will soon be shattered, as David Lynch’s deft narrative prowess reveals what lies beyond the facade. This fascination with the darker side of apparent happiness is a Lynch trademark that enriches his films and enhances the mystery he longs to inject in his narratives.

As with all of David Lynch’s output, Inland Empire confounds the mind and leaves those that stick with it in a state of confusion and uncertainty. Perhaps the most difficult of Lynch’s films, Inland Empire, clocking in at three-hours long, is the film that asks the most of its viewers. Inland Empire leaves itself open to multiple interpretations, the aspect of the film I find most absorbing is the possible commentary Lynch is making on the notion of the self. Identity is something Lynch explores through each of his films, often giving multiple identities, personalities, or concept of the self to one character. I occasionally wonder if this isn’t Lynch offering his perception of person-hood and the multiplicity of the human mind. It seems that through Inland Empire Lynch could be suggesting that the idea of the self is one that we can never realize, just as Nikki Grace (Laura Dern) feels herself becoming more of the character she is portraying. The more time that the audience spends in the world of Inland Empire, the more we see Nikki losing her grip on her own identity, as it merges with the character she is playing. The world around the actress also seems to morph into the world of the filmed re-make she is working on.

Perhaps this is Lynch’s way of expressing that there is so much fluidity in the world that it is hard to discern between what makes up ourselves as opposed to that which influences us. Perhaps, also, Lynch is suggesting that there is no difference between influence and person-hood, and that which influences us merges entirely with who we are as a person. Of course, Lynch may not be posturing any of those notions; these ideas make up my relationship with Inland Empire and how it may be interpreted. Being a film open to such interpretation, maybe Inland Empire is a further exercise of Lynch’s into abstract expressionism and is only meant to conjure up that which the individual audience member gets out of the film. Each viewer will bring to their viewing a unique relationship with their identity and what defines themselves, therefore, maybe Lynch was merely gifting us a vehicle to think about ourselves and allow ourselves to discover something new or see something different about ourselves for the first time. Whether Lynch is presenting an opportunity to learn something about our identity or he’s suggesting that no fixed identity exists, Inland Empire is a brilliant trip with David Lynch through the subconscious.

Inland Empire is both distinctly a part of David Lynch’s oeuvre as well as uniquely separate. The film gives us a tour-de-force of Lynch regulars, illustrating the gift he has for casting people in the perfect role. Laura Dern traverses the emotional range of her character flawlessly; Harry Dean Stanton handles his grisly mysterious character with ease; Justin Theroux carries his controlled yet gentle essence like no other; Grace Zabriskie manages an unsettling, even frightening performance as only she could. Lynch’s talent for recognizing the particular gifts of his regular pool of characters and putting them in the exact roles they are meant for in each of his works make his films shine and add a familiar Lynch touch. In addition to the excellent use of his regular actors, Lynch also exemplifies a knack for selecting the perfect actors for their cameos in his films, as well. I always forget until I rewatch Lost Highway that Richard Pryor is in the film. I always appreciate seeing Pryor as a bit of perfect casting for a minor role and as a way to continually surprise his audience. Similarly, I forget that William H. Macy is in Inland Empire until I’m feeling valiant enough to watch the film again.

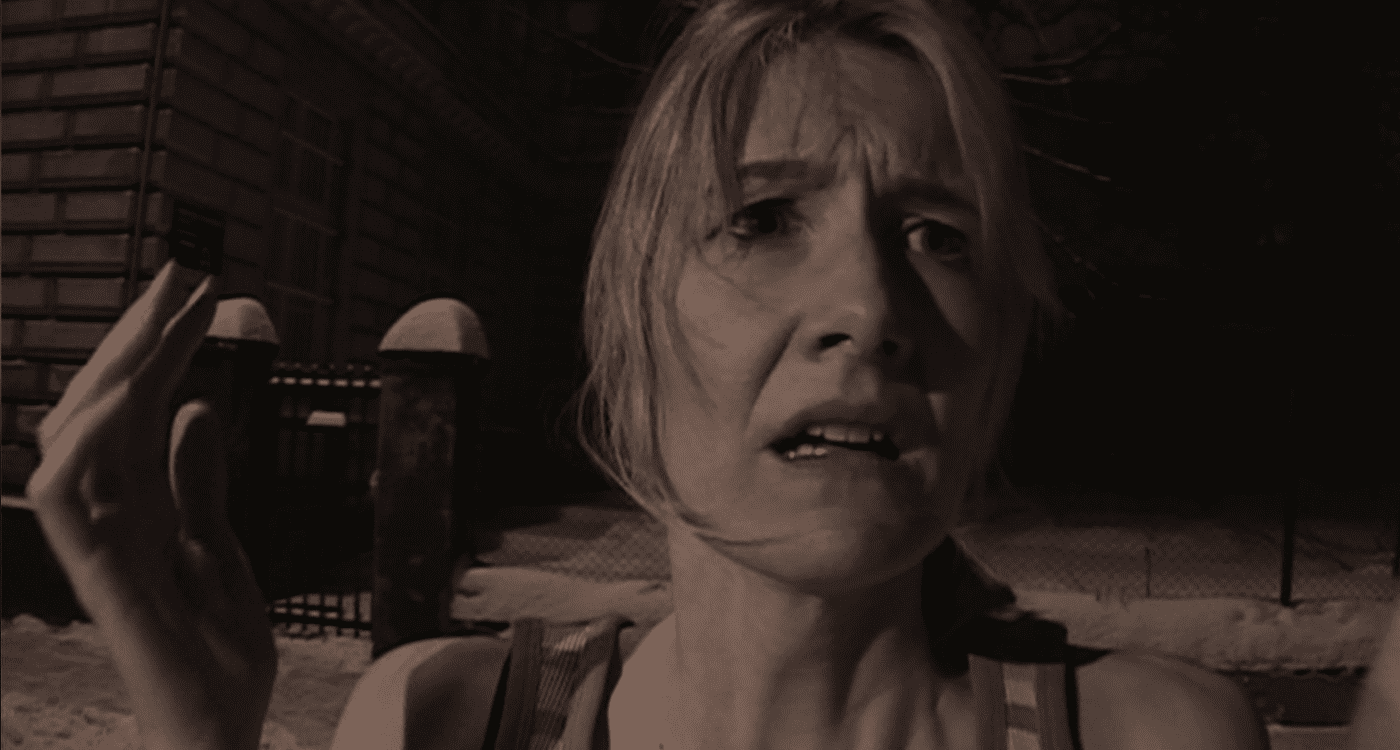

Another aspect of Inland Empire that cements it as a distinct part of David Lynch’s filmography is the way he films faces throughout the film. Just like in Mulholland Drive, Lynch’s camera in Inland Empire zeroes in on a face, showing it out of focus, then slowly brings the face into focus, a technique that is particularly ideal for Inland Empire as a tool for illustrating the unhurried way Lynch carries the narrative of the film together. There is a familiar color scheme, primarily made up of red and green, especially the curtains, that also makes clear that one is watching a David Lynch film. Of course, no film by Lynch would be complete without a stellar sound design, another aspect of Inland Empire that is a clear indication that the film fits in David Lynch’s wheelhouse.

The most significant way Inland Empire presents itself as a departure for Lynch is his complete immersion into the world of digital video to shoot the film. The first of Lynch’s films to be shot on digital video, Inland Empire represented an experiment in production for the veteran auteur. Lynch used cheap handheld cameras to shoot the film, producing a look similar to the genesis of the film which first appeared, in parts, on David Lynch’s website. The high-definition filming mutes the sunny bright promise of L.A. in a way Lynch also seeks to achieve through his narrative. By using a consumer-grade model camera, Lynch was not attempting to replicate any aspect of traditional film production but instead seemed eager to explore all of the unique features that digital media could provide. Digital video offered the perfect opportunity for Lynch to indulge in the parts of movie making he loves most. Long takes, and multiple takes are easier to achieve through digital video due to the low cost and reduced setup time. The harsher look of a movie shot digitally, the grainy low-resolution video, and the weaker color contrast is undoubtedly something that enticed Lynch when thinking of the descent into madness he was looking to film with Inland Empire. What better way to deconstruct the romanticized promise of Hollywood than by producing that very film in the least Hollywood way possible. As starkly contrasted as Inland Empire is from the rest of Lynch’s filmography in its method of filming, I can’t imagine the film any other way. As with seemingly everything else in David Lynch’s career, he latched onto digital media at the precisely right time as it enabled him to produce a doom-laden atmosphere that Lynch could not have achieved in a better way.

The audience is left asking a lot of questions as the credit dance party scene at the end of Inland Empire takes place. The tagline of the film promised us “a woman in trouble,” and there indeed was, at least one, woman in trouble. We never really gained a good sense of what was going on with the family of rabbits or how precisely they fit into the story. Perhaps, despite the declaration in Twin Peaks, it really was about the bunny. We’re likely never to know, nor are we likely to ever get some narrative direction to what Lynch intended Inland Empire to be. What we are left with is a fantastic ride through the powers of the mind, and perhaps our own subconscious. Inland Empire is intense, almost like a nightmarish fever dream brought to you by a master of embracing the uncomfortable. Inland Empire stands as a line in the sand between the casual David Lynch fans and the devotees, even frustrating those of us who list Lynch as our favorite filmmaker. After Inland Empire in 2006, Lynch wouldn’t make another film until he blessed fans with Twin Peaks: The Return last year and I can only hope that reemergence means we can expect even more films from the mind of David Lynch, and the invitation to dig deeper and explore worlds within ourselves.

One of the female Rabbits says “I’m going to find out someday” to a male rabbit. Presumably her husband, implying that she’s accusing him of cheating.

A major theme of the film is the effects that infidelity can have on a couple, and how much the woman is to blame if she ends up looking elsewhere, especially when the husband is abusive and controlling.

The film presents the argument that women find themselves in guilt ridden positions in life because of their perceived status as dirty, or whorish and many times end up there because of the way men have physically and mentally abused them, how the men see them as “animals” (a reoccurring motif in the film)

The Sue/Nicky character that monologues to the psychiatrist at the top of the stairs recounts horrific stories of violence perpetuated by men in her life, and the way these men have harmed her has formed her own perception of herself. Her Identity.

This is why Sue/Nicki hangs out with the prostitutes at the end. She sees herself as nothing but dirty. She’s not entirely blameless for her actions, as indeed the “little girl opened the door” and evil was born, but the men in her life have pushed her down so far that most of the blame lies with them.

The ending of the film has Nicki killing a reflection of herself and reclaiming her identity.

Inland Empire is a feminist piece through and through

Inland Empire is such an under appreciated piece of film. I dare say it’s not even a movie, but possibly something different altogether. In any case, it remains the sole piece of motion picture I’ve seen that actually quenched my thirst for weirdness.

Thank you for your well-articulated thoughts.

Inland Empire is such an under appreciated piece of film. I dare say it’s not even a movie, but possibly something different altogether. In any case, it remains the sole piece of motion picture I’ve seen that actually quenched my thirst for weirdness.

Thank you for your well-articulated thoughts.