Through the mists of time, back in a day where the only ways to watch a movie at home was either through renting a chunky piece of plastic for 24 hours or watching it on TV with commercial breaks, there was this thing called a “cult film.” This kind of film was quite often met with critical derision or a concerned frown when it was released and then gained some kind of notice through midnight screenings, showings on cable, or at your dependable video rental store. Ignored, offbeat movies would then have a second life, fans would create artwork and these old things called fanzines. You could send an envelope away and get your devotion to the movie rewarded by someone far away who felt the same way you did.

This was the way the old definition of a cult movie worked and it led to a second life for films such as Pink Flamingos (1972), The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975) and The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai Across the Eighth Dimension (1984). As time has moved on, defining the cult film became more difficult as the old methods of having to work for your fix of viewing or corresponding with the fandom faded with the proliferation of the internet.

In the modern age, everything is accessible and on-demand at the touch of a button. You no longer have to import a DVD, travel several miles for a screening or wait all that long for a legit release of anything really. The cult film now feels manufactured rather than something that happened due to artistic freedom or fluke. The lower budget end of things has gone through a phase of trying to imitate its cult past and this has resulted in clones of all those things you used to love that you thought nobody but you knew of. It has even been taken up by the big players with huge budget sequels made to the likes of Tron (1982) and Blade Runner (1982). It has become easier than ever to meet like-minded fans of that unique property, throw a stone on the web and you will meet an even more rabid fan than you of the work of Don Coscarelli (Phantasm 1979).

My first exposure to the cult film occurred in my early teens. There was this Sunday night slot on BBC 2 devoted to exposing the strange, the unloved and the unique. Moviedrome was presented by director Alex Cox who gave us informative and often humorous introductions to the film or films we were about to watch. As a result, Moviedrome was responsible for a lot of the films that captured my imagination and showed me a wider world. It was the way I first saw films such as Q: The Winged Serpent (1982), Assault on Precinct 13 (1976), Trancers (1984) and Barbarella (1968). It would have been shortly before I became aware of Moviedrome that I saw my first cult movie directed by Cox himself.

Repo Man (1984) is everything the cult movie was in the early ‘80s. Reflective of the times themselves, perfectly soundtracked and made with nary a concession towards its target demographic. In fact, it positively spat in the face of the word “demographic.” That summer night watching this film unfold was the beginning of something massive for me, a change that would coincide with hitting that awkward age of 13 and starting to question the old ways. Not a rebellion exactly, but certainly starting to suspect some people were maybe full of shit.

The film takes place in the fictional Edge City, which is quite blatantly a stand-in for Los Angeles with landmarks present from most of the films of the time. Young high school drop out Otto (Emilio Estevez) works at a supermarket, whilst watching his ex-hippie parents zone out to bad TV and wasting time rebelling with his fickle street punk friends. One day quite by accident, Otto meets Bud (Harry Dean Stanton) a repo man who trawls the city looking for cars that are behind on payments and bringing them in for the commission. Otto is then inducted into a bizarre sub-culture with its own code and adrenaline junkie philosophy. Meanwhile, a high-priced target Chevy Malibu wanders the city with a dying driver and something otherworldly in the trunk.

In a strange way, Repo Man feels like a precursor to another future cult film named Fight Club (1999). It likewise deals with the disenfranchised and the resulting new philosophies as just another way of coping with the pains of modern living. It also very definitively feels like the vision of one person. Alex Cox graduated film school in 1977 just as the punk scene was really taking hold and new wave was about to make its presence felt. Cox somehow convinced former Monkee Michael Nesmith to produce the film and Universal Pictures backed it to the tune of a million dollars. The film was a box office flop on its limited release, but the success of its soundtrack album featuring Iggy Pop, Black Flag and Dead Kennedys meant that it got a single screen re-release in New York where it played and played for months and was then quite popular when screened on cable.

Harry Dean Stanton’s character Bud shares a very punk-like philosophy despite being dressed in a crumpled suit with actual employment and a drug problem. The repo man code seems to have a very similar structure to Isaac Asimov’s Three Laws of Robotics, and this was probably an intentional piss-take. The code is loaded with disdain for the status quo, but then other members of this squad espouse differing philosophies at Otto. One repo man seems to be a Scientologist and the company mechanic is very much into the unexplained and aliens as being the reason we humans are all here in the first place. Although initially attracted to this rebellion of legal theft as an alternative to a life of minimum wage, Otto soon finds the new life just as loaded with hypocrisy as the rest of the world.

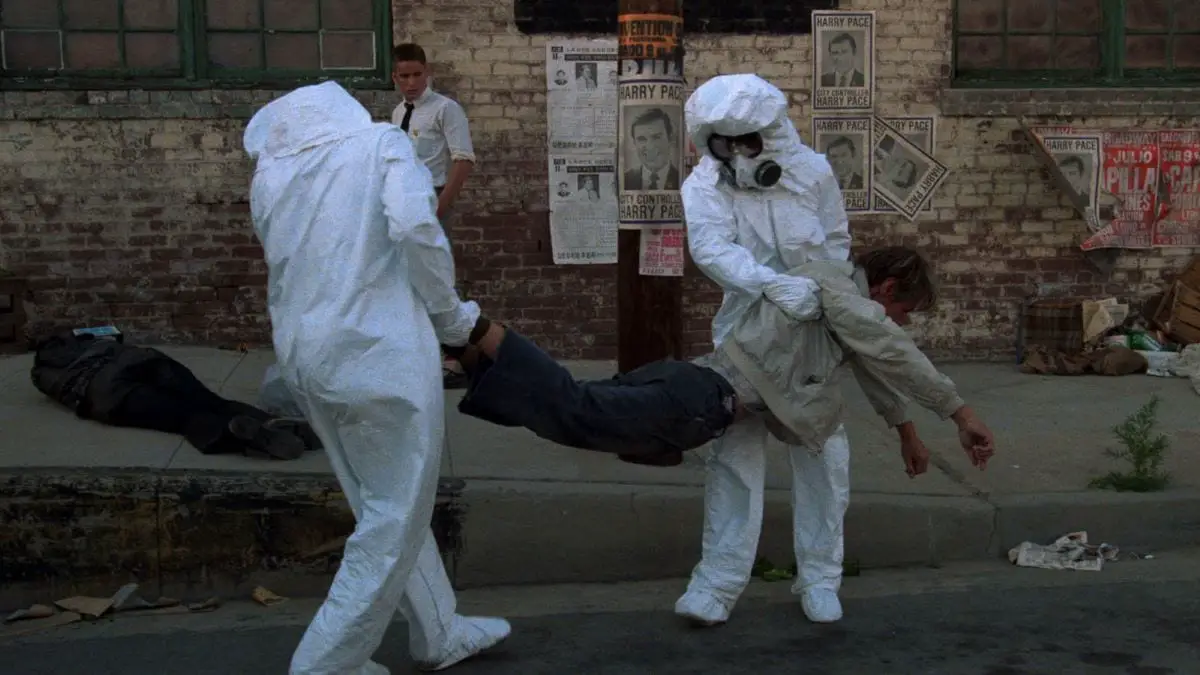

Repo Man is very much a criticism of Ronald Reagan’s America, a world full of sell-outs and failed rebellions. In one scene Otto wanders streets filled with homeless people as he recites that evenings prime time TV line up. Otto’s parents are ex-hippies who now sit entranced by a TV evangelist whom they have donated all of their money to in the quest for easy answers. Most blatant of all, and a happy accident of the low budget, all products such as beer, cornflakes and tuna fish are simply labelled with a white label telling us what is inside. This is what it was like to be young and angry in the world of the 1980s, surrounded by the constant selling of an empty lie.

The presence of the alien in the trunk of the Chevy is perhaps a comment on the growing mistrust of government post-Watergate. This thing lurches around the city and consumes anyone who looks too closely. Although the car and its contents become a McGuffin, it scarcely matters against the consumer culture that Cox is mocking throughout the film. When the car is finally retrieved at the climax, Otto rejects the stable option of a healthy relationship with the love interest in favour of taking the car. The newer flashier item winning in a culture always looking for bigger and better.

In the current climate with record unemployment and dishonest, corrupt leadership, Repo Man feels more relevant than ever. We are all looking elsewhere for some kind of solution and Repo Man’s mixture of cultural critique and the unexplained feels more pertinent than ever. It is that rare example of a cult movie of the time that stands up, and much of that is thanks to us coming full circle as a civilisation once again.

Following Repo Man, Alex Cox went on to direct the Sid Vicious movie Sid and Nancy (1986) and then followed that up with an ambitious real-life story Walker (1987) based around the life of William Walker, an American who led a coup in Nicaragua. Walker took massive liberties with the story itself and reality and resulted in a box office disappointment. Cox has struggled to reach the heights of his earlier work, with much of his ‘90s stuff being flawed by studio interference or desperately experimental. Along with Walker, Repo Man remains his best work and a poster child for what the cult film once was.

The conundrum I had at the end of watching Repo Man is wondering whether or not the cult film actually exists anymore. Anything strange or left field is instantly labelled as a cult by those seeking to pigeonhole a product for a guaranteed audience and then there is the cinema of Wes Anderson which has gone mainstream. The old definitions no longer apply due to the way in which we now consume media. Possibly the last true cult film was Donnie Darko (2001) if we are sticking to the old understandings of the term, but then in the last days of the cinema before the recent shutdowns, I did notice the film Underwater (2020) playing at midnight for quite a while followed by people discovering it and loving it when it came out on VOD.

The work of Alex Cox is definitely worth seeking out should you want to delve into the old-style true-blue cult movies. With all of the anger in our current world, it is worth reminding ourselves that the more things change, the more they stay the same.