Next week begins one of the great fortnights of sport, Roland Garros, also known as the French Open, or, in William Klein’s brilliantly shot 1982 documentary, simply The French. Klein’s film, shot with nearly unfettered access at the 1981 French Open, is one of the great documentaries of sport, an astonishingly intimate look behind the scenes at tennis legends competing for one of the sport’s coveted Grand Slams. “Presented by” Wes Anderson and re-released for a national theatrical and streaming rollout, The French serves up an ace with its verité-style intimacy and insights.

Known primarily as a lauded, even legendary photographer, director William Klein is also a film satirist (Who Are You, Polly Magoo?) and documentarian (Muhammad Ali, the Greatest; Eldridge Cleaver, Black Panther; and The Little Richard Story) and has made hundreds of commercials, many of them groundbreaking. Long a fan of sport and social criticism, Klein found at the 1981 French Open a crucial moment in a crucial year in the history of the game. With three camera crews, Klein was given exclusive, unprecedented access to the tournament. The result is a remarkably intimate presentation, one not limited to center court, but across the grounds, from the locker rooms and players’ lounges to the TV studios and the players’ boxes, massage tables, organizer’s offices, practice courts, and entry gates.

Anyone who thinks tennis an antiseptic, orderly sport will have their misconceptions shattered by The French. The two-week tournament is a muddy, sweaty, grimy, labored contest of will and stamina. Played on terre battue—in English, “broken Earth” that is crushed red brick—the game is one where the grime not only slows the ball, making outright winners more difficult and less frequent; it permeates the pores, affixes itself to sweat, and pocks the players’ shoes, socks, and kits as they compete. Whoever will win the French will win, in a single-elimination bracket of 128 players, seven straight matches, each of them its own unique test of guile and guts.

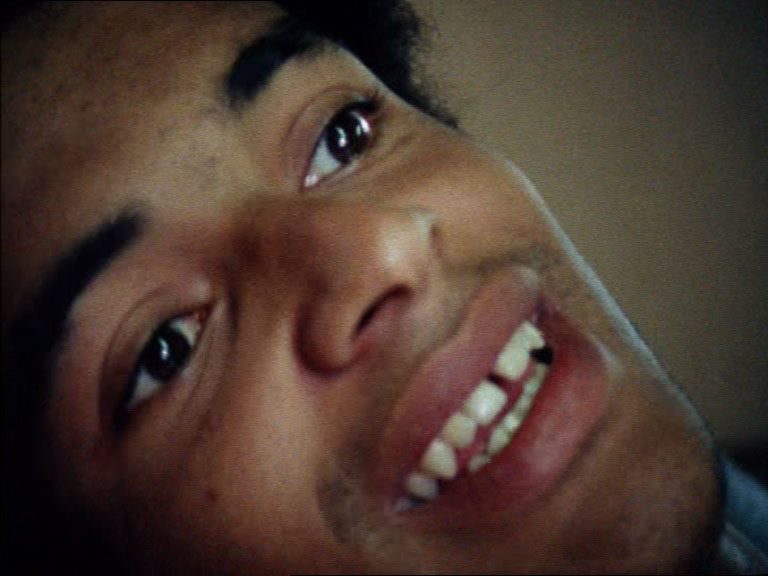

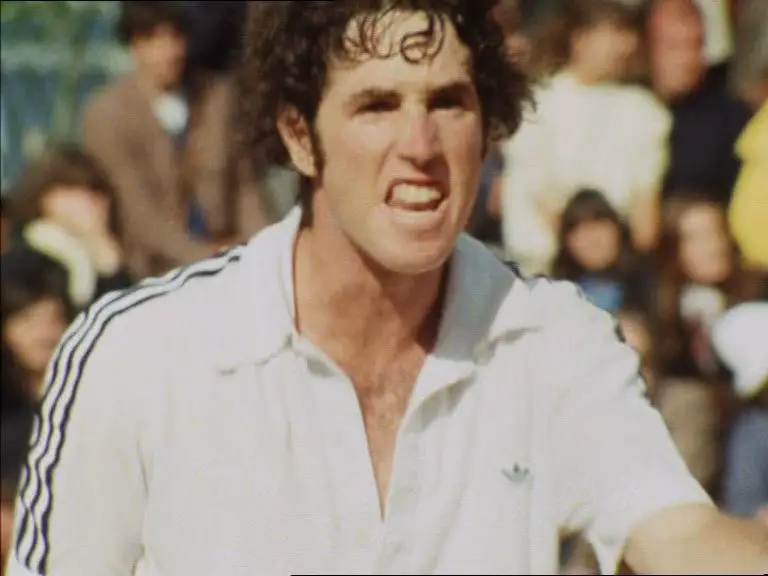

In 1981, the sport of tennis was enjoying a heyday based largely on the competitive rivalries of its biggest stars. For the women, Chris Evert-Lloyd (as she was known at the time) and Martina Navratilova’s dominance was rarely challenged. On the men’s side, titan Björn Borg had won three straight and five total French Opens as well as the then-unprecedented five straight Wimbledon championships. His main rivals, Jimmy Connors and John McEnroe, were less accomplished on the clay, having never won Roland Garros, but a pair of young twenty-one-year-olds, the charismatic Frenchman Yannick Noah and the charisma-free Czech Ivan Lendl, aspired to an upset.

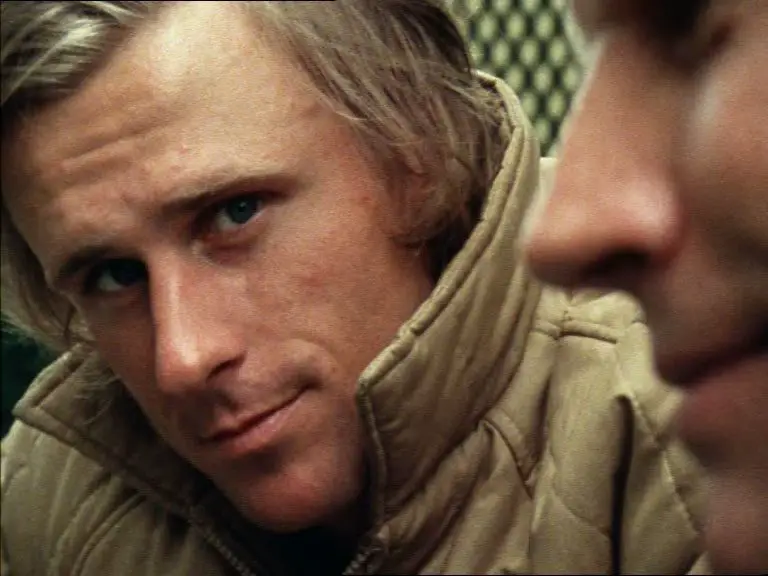

Klein’s film, shot in the verité style that largely eschews talking-heads interviews, overt voice-over narration, or the use of non-diegetic content, is organized simply with chapter marks indicating each day of the fortnight’s event. Players, including those like Borg who need no introduction and dozens of others who do, are identified simply by name. On one or two occasions, Klein will use some brief non-diegetic music or render a climactic moment in slow motion. But for the most part, what one sees in The French is simply shot and handsomely composed with, again, remarkably intimate close-up detail of competition—and little artifice.

Some of that of course takes place on the courts themselves. Rather than rely on broadcast footage, Klein’s own crews set up angles that allow for close-ups of the players as they grimace through grinding rallies. The excellent sound recording allows us to feel the impact of tightly strung gut against the ball’s fuzzy pelt or the player’s shoes sliding across the clay. Some matches are delayed by rain; others played (to McEnroe’s considerable consternation) in a slow mist; a few under a hot, draining sun. Klein never overlooks the fan, and some of the film’s most memorable shots are of the event’s patrons’ heads swinging in unison to follow the ball.

In 1981, the sport was played almost exclusively with wooden rackets, their small 70″-ish head sizes limiting the amount of power and spin a player could impact upon the ball. A clay-court rally was more a matter of finesse, guile, and fortitude than the power that impacted the game in the 1990s when composite graphite rackets with much larger head-sizes and polyester strings became the norm. Klein understands this aspect of the game well and focuses on the chess-like point construction necessary to win.

Fascinatingly, the game itself—the serves, faults, aces, rallies, winners, errors—has changed only a little since 1981. Other changes are more obvious, most prominent among them the absolute lack of any real security or crowd control. Throngs of adoring fans mob and grope Borg wherever he goes: though he says little, his charisma pervades every interaction with the fans and the camera. Crowds press against entry gates. At the end of a match, random admirers casually walk on court to congratulate or console the competitors. After a loss to the aging Ilie Nastase, a visibly frustrated Eliot Teltscher yells “Whaddya want from me? These f*cking guys are mobbing the sh*t out of me!” With the unfortunate on-court stabbing of Monica Seles by a crazed fan in Hamburg more than a decade away, that little thought is given to any kind of crowd control is especially apparent today, two years into the current pandemic.

Fashionistas will love the tighty-white short-shorts sported by Noah and the other men, the on-point Ellesse skirt-blouse ensembles Evert and her opponent Virginia Ruzici wear, and Borg’s sassy Diadora kicks. Other time-capsule gems include wadded-up scraps of paper as entry tickets and draw selections; land-line telephone booths for journalists to transmit scores and reports; and liberal cigarette smoking in the stands, most of it by Nastase’s coach and noted tough-guy Ion Tiriac. When Noah receives a gift package by mail of powdered supplements, no one in the room seems to suspect terrorism.

Tennis being one of the few sports where men and women compete together, if separately, at the same event, the question of gender equity comes into play as the organizers debate how to reschedule matches after a rain-out. Matches are set to begin an hour early, but it’s decided “a few” men’s matches will begin alongside the women’s—so the women don’t get “all up in arms” about it, as one of the male officials opines. Unfortunately, the women are given some short shrift in Klein’s film. A quarterfinal match between Ruzici and Evert, a study in contrasts, is highlighted with a great set of close-up reaction shots of the talented, volatile Ruzici struggling to contain her composure against the absurdly calm Evert. And after, Ruzici calmly and accurately self-assesses her own inability to close out the match. For the women, though, that match is about all you get, save for a few points of one of the event’s less memorable finals, contested by a champion you may remember and an opponent I’m confident you won’t.

The French is a men’s event first and foremost. But to be fair, 1981 was a significant turning point in the history of the men’s game, and that year’s French evidenced more than a few harbingers of change to come. Borg, who had at this point won a commanding 10 Grand Slam championships, had been for five years the face of the sport internationally. His closest competitors, Connors and McEnroe, could not unseat him at Wimbledon, where he’d won five straight, nor at the French, where he’d lost only one match in eight years.

Klein gives some considerable attention to a quarterfinal match between McEnroe and a composite-racket-wielding Lendl, one that would presage their epic 1984 final a few years later, and to Noah’s battle versus former champ Guillermo Vilas. As the decade progressed, it would do so without Borg, who played only one event in 1982 and suddenly retired in 1983 at the age of 26. At the 1981 French, though, Borg is undisputed king. At one point in the early rounds, Klein shows the champ enter the court with his competitor, an unknown Hungarian, to begin his warm-up. Suddenly, Klein cuts to Borg donning his track-jacket and the sound of the umpire declaring “Jeu, set et match, Borg.” The effect is comic: Borg won without raising a sweat. The championship match is not so easy, though, and intimates the game is soon to change, with or without the king.

Most of the time, the editing is less obtrusive, and even at two-plus hours, the film glides by effortlessly as Klein and his crews take their cameras across the grounds. There’s little false modesty or prudish censorship as the women shower or Noah, dressed down to a jockstrap, gets his post-match rubdown. The less-heralded players crowd on a couch to watch those few players left in competition, boasting how they would take down a Lendl or Borg. (They wouldn’t.) At every turn, The French‘s study in sporting intimacy is something to savor. When we fans watch an event from our seats or on our televisions, all we see are the strokes and the shots, never the pre- or post-match routines and confessionals.

Netflix has announced a behind-the-scenes documentary of the tour currently being shot at this year’s Australian Open, Roland Garros, and the other slams. It’s difficult to imagine that it can offer up anything as intimate as William Klein did with The French. Today’s players are typically isolated from their fans, ensconced in their entourages, following cautious security protocols, and trained in public-relations discourse for their required press conferences. The few behind-the-scenes intimations that exist, like Netflix’s Garrett Bradley-directed Naomi Osaka, seem more intended to regulate the players’ media brand than to offer true character insights. It remains to be seen if the kind of access Klein was granted in a pre-social-media age can exist today.

In the meantime, as you gear up for this year’s Roland Garros and its competition—whether Novak Djokovic can tie Rafael Nadal’s record 21 Slams by defending his title against Rafa and an ascendant star in Carlos Alcaraz, or whether Iga Świątek can extend her remarkable 28-match winning match streak against the field—look for William Klein’s brilliant 1982 documentary The French in theaters and on your streaming services beginning March 20.