With disheartening speed, Wes Anderson’s anthology of Roald Dahl adaptations ended up lost in the Netflix algorithm. Perhaps this is just the natural ephemera of streaming content; perhaps it’s partially the consequence of Dahl’s increasingly polarizing reputation surrounding his antisemitic sentiments; perhaps short-form cinema is simply not in vogue; or perhaps the lack of interest is merely the result of Anderson’s treatment of the shorts, which is riddled with esoteric mannerisms and ultra-stylistic contrivance. Whatever the cause, the sudden submergence of the short films into the catacombs of the platform is a shame. Regardless of what one thinks of Dahl’s personal legacy or Anderson’s aesthetic quirks, the adaptations are wonderful.

In what has turned out to be a career-best year in terms of quality and productivity, Anderson’s omnibus of Dahl-adapted shorts follows quickly on the heels of Asteroid City. The two projects, while wildly dissimilar in some ways, both tap into Anderson’s artistic preoccupation with breaking not only the fourth wall but the fifth, sixth, and seventh wall as well. His worlds have grown so postmodern that the subtle differences between arrant artifice and aesthetic semblances are no longer existent: everything is ludic, liminal, illusory, and amorphous. His cinematic universe is truly an aesthetic funhouse of endless textural layers, and his ability to enfold, refold, and unfold his dollhouse mise-en-scènes is truly a sight to behold.

At the same time, the byzantine plot structures and multilayered meta elements in Wes Anderson’s recent cinematic releases have become a sort of litmus test for many—a critical determinant on whether one celebrates the auteur’s output as among the very best in the American film industry (see: Richard Brody’s celebration of Asteroid City in The Best Movies of 2023) or as one of the most grating (see: Owen Glieberman deeming of Asteroid City as one of The Worst Movies of 2024).

Personally, Asteroid City (which I reviewed earlier this year) is easily in the upper echelon of the 2023 releases I’ve seen, and his Roald Dahl experimentations far exceed it, topping my list as the most exciting release of the year. In the same vein that Paul Schrader anointed Asteroid City as Anderson’s apotheosis (proclaiming “he has distilled his design-driven anti-empathy film style to its essence [and] it’s hard to find a comparable film.”), Anderson’s Roald Dahl collection pushes this apotheosis one notch higher, becoming his new acme (for me).

Not a second is wasted in any of the four short films, ranging from the 39-minute-long The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar to the other three 17-minute-long entries (Poison, The Swan, The Rat Catcher). As Bilge Ebiri astutely notes in his recap of the Henry Sugar short, “characters here often speaktheirlinesreallyfast, as if they’re tryingtofittwohoursworthofmaterialinto39minutes,” packing expansive prosaic content into a short span of screen time. Succinctness is certainly a benefit of the narrators’ accelerated loquacious cadence, but I’d posit the purpose of the hyper-speed narration goes beyond brevity.

It feels as if Wes Anderson is as concerned, if not more concerned, with examining the very nature of literary adaptation as he is with curtly conveying Dahl’s keen collection of surly short stories. Echoing the Matryoshka-doll structure and tiered scaffolding of Asteroid City (which, as I chronicled, operates as a play within a play within a throwback TV program), each short is, in essence, a reflection on the way various mediums and styles of storytelling function and transmit information, meaning, and entertainment.

As Richard Brody keenly points out, “The four stories are, essentially, dramatized audiobooks, something like music videos for literature.” This may sound like a slight; it is not. Of course, Anderson’s narrative gimmickry exists within a long-entrenched postmodern tradition of winking and nodding at the malleability of form, popularized in everything from Joycean literature to Godardian cinema. But as Brody goes on to point out, Anderson blurs the lines between meta-commentary and narrative even further: “[Anderson] stands that notion on its head [insofar as he] never breaks the framework of classically realistic drama because he never establishes it in the first place.”

This is a critical distinction and insight into what makes Anderson’s playfulness so ingenious. To praise Wes Anderson or any director (an auteur or not) for breaking the fourth wall would be somewhat moot at this point. Everything genre and class of movie—from The Lego Movie to Deadpool to Isn’t It Romantic—has caught onto the meta-narrative bandwagon. But where most films are content pointing out the central conceits and underlying artifice of their own creations, Wes Anderson is after something exponentially more elusive and interesting.

Richard Brody further acknowledges Anderson’s capacity to flip the fourth-wall formula by working in reverse: “It is not a question of characters breaking the action to address the camera but the reverse, and, for this reason, the direct address comes off as natural and central, and the acted-out drama as strange and supplementary.” I’d agree, but push this line of thought further: Anderson seems fixated on collapsing the walls around his cinematic worlds entirely. HIs goal is not to separate the telling from the illusion but to fuse the categories of suspended artifice and conspicuous storytelling/representation together.

Everything on screen in the four Dahl shorts fundamentally functions as a narratively-contingent construct that can be altered, disrobed, and rearranged at any moment. Eyebrows are removed, backdrops disappear, perspiration is manufactured with spray bottles, and blood spots are meticulously dabbed onto characters’ faces and costumes. Narrators constantly vacillate between acting and telling—transitioning fluidly and abruptly between a direct audience address and dramatic engagement. We are always being told a story; in Derrida or Borges fashion, there is no difference between the simulation and the real, the map’s topography and its legend: we are always inside the multidimensional simulacra of storytelling.

A cynical lens might see such artistic interventions as indulgent and supercilious. However, Anderson’s endgame does not seem as pretentious as merely laughing at or exposing the fundamental superficiality of storytelling. To do so would be somewhat contrived; after all, late-stage postmodernity has exhaustively eviscerated the moviemaking formula. Instead of clever or smarmy deconstruction, Anderson insists on exploring the resplendent diversity of narrative possibility.

The metafictional ambition most prevalent in this phase of Wes Anderson’s singular yet ever-evolving oeuvre is not to be above the material but immersed fully and wholly within its multiple modalities and to morph between them with nebulous fluidity. Instead of cackling at the aesthetic distinctions between art and artist, form and function, sign and signifier, reference and referent, Anderson approaches the post-structural material with sincere curiosity. His modus operandi is not mockery but mythmaking, weaving together concurrent strands of storytelling. His trickery is rooted in the earnest desire to see how storytelling can move—not merely horizontally, vertically, backward, or linearly, but with proliferating and rhizomatic omnidirectionality.

The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar

While the order in which Anderson’s Roald Dahl anthology can be viewed is somewhat interchangeable, The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar is the most logical starting point. It is the only short film to initiate and establish the overseeing and omniscient position of the fictionalized Roald Dahl (Ralph Fiennes), who appears elsewhere in the anthology. Here, Dahl serves as the inaugural framing device, first chronicling the cozy details of his writing regimen (enumerating his choice of writing utensil, the amount of rubber eraser detritus accumulating each day, and coffee and chocolate nutritional/cognitive aids) in a detailed prologue.

Dahl then begins the narrative train with the play-by-play description of Henry Sugar (an alias of a wealthy arriviste, played by Benedict Cumberbatch) stumbling upon a book of a doctor’s report of Imdad Khan (Ben Kingsley) at a party populated with parvenu—nouveau riche who pursue money for a pastime and serve as “part of the decoration.” The book’s contents unfold into another story, and soon, The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar becomes a narrative within another narrative within another.

Inside this dusty book is Dr. Chatterjee’s (Dev Patel) transcribed interview with Imdad, a rarefied mystic who had arrived one day at Chatterjee’s hospital requesting to have his eyes professionally concealed so he could perform a circus act without suspicion of cheating. After gluing, placing dough, and bandaging Imdad’s eyes, Dr. Chatterjee is stupefied to see Imdad easefully opening doors, descending stairs, and hopping on a bike after circumnavigating the hospital.

Later that evening, the doctor visits Imdad’s circus act, which is not shown onscreen. Instead of seeing the circus act itself, the camera lingers on Dr. Chatterjee sitting amid the awed circus audience under a cartoonish spotlight. Speaking directly to the camera, Dr. Chatterjee explains witnessing Imdad throw knives around a boy’s body, shooting a can off a boy’s head, and threading a needle while blindfolded and donning a metal barrel over his head.

Wes Anderson refrains from showing these circus feats intentionally. Forced to merely hear about them secondhand, the language of the source material itself and the performance of the narrator’s oration are forced to hold our gaze. Scientifically perplexed by the performance, Dr. Chatterjee relays his amazement, and we must use our own imaginations to picture the magical feats. We are teasingly left as vicarious voyeurs, relegated to the bookish stance of imagining the events ourselves. It is purposely un-cinematic, taunting the viewer by privileging the storyteller over the story.

Amazed by the circus act, Dr. Chaterjee enthusiastically offers to record Imdad’s methodology and publish it in the British Medical Journal. Imdad agrees to disclose his secrets, recapitulating how he came to be an apprentice of The Great Yogi (Richard Ayoade) in the jungle. As Imdad begins chronicling his apprenticeship, a gaudily embroidered curtain (doubling as a narrative tableau) animates the spoken events behind him. Soon, the cartoonish curtain rises to reveal a painted illustration of jungle foliage. Before long, this illustration is split ajar as dual doors retract to unveil multiple layers of jungle. The effect is a cinematic pop-up book, and slowly, the camera creeps forward, illuminating what was previously assumed to be two-dimensional drawings as three-dimensional props.

Anderson’s use of space here is inventive and thoughtful. Everything jarringly becomes voluminous and thus illusory as the background and foreground vacillate between flatness and depth. This visual motif recurs throughout the entire Dahl omnibus as the textures of the background transition from a canvas to a portal to a screen to a stage with eclectic visual chicanery.

This unmoored state of metamorphosis (with settings constantly unfurling into new milieus) turns The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar into a world of optical illusions, deflections, and deceptions. Much like a carnie or a magician, Anderson’s stylistic misdirection turns him into a spastic showman presenting an unpredictable and elusive pageantry of props and signposts. Utilizing clever production design and cinematic legerdemain, Anderson forges a wonky unreality within the strict spatial parameters of moviemaking.

Ultimately, the backdrop behind the props becomes a fully dimensional space. The Great Yogi appears, meditating so intently he levitates. With pointed humor and subtle irony, we visualize this feat as a sleight-of-hand. Instead of levitating, the yogi turns a painted box on its side, causing the façade to blend in with the background and disappear by camouflage.

Stunned by the miraculous illusion, Imdad, narrating this segment, enters the vignette/set he’s narrating. However, The Great Yogi doesn’t react like a character might if interacting with another character onscreen. On the contrary, he takes cues as a performing puppet, reenacting Imdad’s anecdotes by pantomiming various acts as their spoken verbatim (i.e., mimicking a throwing gesture as we learn he threw a rock at Imdad for startlingly interrupting his meditation session).

Imdad may dictate The Great Yogi’s actions like a ventriloquist onscreen, but he serves as a pupil/understudy in the autobiographical retelling. Under the tutelage of The Great Yogi, Imdad masters the art of meditation, routinely staring into a candle flame so intently at eye level that he learns to picture faces and see through things. Imdad’s decision to deploy the clairvoyant fruits of prolonged concentration in circus acts is never explained. Notwithstanding, this venture leads to his circus act and eventually to the interview with Dr. Chaterjee, which forms the basis of the book Henry is reading.

After finishing the esoteric tale of Imdad in one sitting (an account we assume had been ostensibly lost and shelved by the annals of time), Henry becomes fascinated by the idea of appropriating Imdad’s magical methods of visual meditation for mercenary means. Soon enough, he devoutly practices Imdad’s candle flame technique, realizing that infrared vision is well suited to his gambling proclivities.

Taking the narrative baton from Imdad, Henry Sugar details his fixation with developing mentalist capabilities and his ultimate success, learning to see through playing cards to win at Blackjack. This section is riddled with unending visual inventions. For example, Henry pretends to drive a car (parked and stationary on an obvious set) while a screen behind him plays a video meant to replicate the movement of driving.

Soon, Henry Sugar anecdotally recounts his gambling endeavors as opposite sections of the screen become obfuscated. Constricted by the boxy aspect ratio, Henry’s direct narration moves from the left to the right to the center of the screen, ending with a circular framing of his face. While one might assume Wes Anderson uses this device solely to enliven the verbal monologue, it seems to have a second meaning. By moving the narrator from one side of the screen to the other, the screen begins to eerily replicate the flow of reading a book (moving from the right to the left page).

Even our normal notion of time grows unfixed as the circadian rhythms between diurnal and nocturnal signifiers (daylight and moonlight) circulate rapidly, rotating at warp speed in the painted background windows. Similarly, as stagehands brusquely pull down curtains and prop up screens, open doors, and rearrange the spatial interface, the phenomenology of the imagination takes center stage.

As concepts of space and time vanish and mutate with chameleonic celerity, everything becomes fantastical, existing in the magical realm of fiction. Suffice it to say, the world of Henry Sugar is one of multiplicity: filled with trap doors, wormholes, and imaginative planes. It is an elaborate interpretation, mirroring the mental fabrications of the mind actively and freely reading. The sole binding meaning is the story’s narration; how the words shapeshift onscreen remains unrestricted.

This imaginative plenum’s protean and mutable nature is echoed in myriad ways. Anderson has helping hands step onscreen to retrieve unnecessary props. He recasts the same set of actors (Cumberbatch, Fiennes, Patel, Kingsley, and Ayoade all play dual characters). He sets up projection screens to simulate actions solely articulated, such as when Henry walks in place while a video approximates his perambulatory movements. A pivotal playing card (a “two of clubs”) is embroidered on the corners of the screen instead of seen on the Blackjack table. The casino turns into the cashier station; the cashier station becomes an apartment lobby.

The cumulative effect of this visual dexterity and figurative flexibility is a feeling of cognitive vertigo. By conflating, expanding, and refolding visual space, everything feels at once bound and infinite, much like a book. There is a strict sense of confinement within the largely static framing of the camera. However, the playful permutations manifesting onscreen belie our sense of imprisonment. Mirroring the act of reading, Anderson keeps the adaptation tethered to the narration while simultaneously digressing, riffing, and unpacking the material with fathomless creative whimsy. He is painstakingly loyal to the text and innovatively unorthodox, reenacting the narration with endless creative transubstantiations.

After honing his craft in a local casino, Henry undergoes a sudden change of heart. Bored with money and facing imminent mortality by way of a pulmonary embolism (a fatal prognosis he acquires by virtue of his ability to see inside his body, which Anderson visualizes by having an “extra” place an X-ray machine before Henry as he is speaking), Henry decides to use his newfound skill set for philanthropic ends. At first, he throws cash off his balcony, which incites a mob reaction depicted merely through the sound of commotion off-screen.

As a result of this commotion, a policeman knocks on Henry’s door to scold him for inciting a riot (notably, the officer is played by Ralph Fiennes, who is also Dahl). The policeman suggests he give money to an orphanage or children’s hospital. Henry likes the idea and travels the world under various guises to win at casinos and charitably fund those in need. These magnanimous globetrotting adventures are shown by the shorthand visual accompaniment of Henry walking off the left side of the screen and returning with a new persona/attire (a mustachioed man with a top hat, a diva, a cowboy). Once again, an ingenious gimmick creates a shortcut for taut narrative messaging.

After Henry Sugar’s death, his accountant (played by Patel) commissions Roald Dahl to write his story under a pseudonym. Here, the realm of make-believe again distorts the line between biography and fiction, real and fantasy. Not only are we receiving a story told multiple times over (Dahl functioning as a posthumous ghostwriter for Henry who recounts Dr. Chatterjee’s transcription of Imdad’s story), but we are told a tale about figures who guilefully cloak their identities beneath manufactured monikers.

However, instead of insinuating foul play or baiting our suspicions, Anderson and Dahl seem indifferent to distinctions between fact and fiction. The nicknames are a mere matter of practicality, and whether these stories are rooted in reality or unreality is ultimately superfluous. After all, is there any difference between the two fungible realms when anything is possible within the unbridled nature of human imagination?

Poison

Poison takes place in India during British colonial rule. It’s a simple chamber piece with an acerbic underbite—a scathing satire of the domineering hubris of British officers stationed in the country. The narrator, Timber Woods (Dev Patel), speaks a mile a minute, recounting the time he paid a visit to a friend, Harry (Benedict Cumberbatch), only to find the man paralyzed with fear from the presence of a venomous krait snake on his stomach.

Sweating and panic-stricken, Harry speaks in a hushed albeit fiercely aggressive whisper, commanding Timber to remove his shoes and then fetch a doctor. Timber heeds his directives and wakes Dr. Ganderbai (Ben Kingsley), a local Indian doctor, to rush over. Ganderbai cleverly devises a set of strategies to manage the crisis, sedating the snake with chloroform and injecting Harry with an antivenom.

The isolated suspense of this short nicely complements Timber’s frantic narration. Lying supine like a patient on a surgical table, Harry serves as a visual vessel for the motor-mouthed story to unfold linguistically and visually. As beads of sweat form on Cumberbatch’s brow and Kingsley’s furrowed squint holds our tension, Patel piques our intrigue by chronicling the doctor’s ingenuity and the threat of the krait’s toxicity.

Once again, Wes Anderson uses Patel’s excellent line readings to deftly segue between the recitation and reenactment of Dahl’s acidic parable. By having Timber/Patel routinely break the fourth wall with direct narration, the fictional dramatics play second fiddle. The result is uncanny and unnerving. As a viewer, one never fully detaches from the form. The actions feel mechanized and rigid as opposed to genuinely inhabited/authentic. Everything is showily conveyed as a recreation–a visual rendition of a permeable text.

This breakdown of the rules separating artifice and representation is nothing novel in itself. Nevertheless, the fluidity of Anderson’s storytelling and the smooth oscillations between the two planes help dissolve the clinical remoteness normally felt when interacting with the medium. Oddly, by detaching from the representation to highlight the creative intermingling that usually occurs behind the scenes, Wes absorbs the audience in the active act of storytelling–becoming collaboratively clued into the constant give and take of interpretation and illumination when adapting a story.

As a result, a fantastic sense of intimacy is achieved; the interstitial walls between story and storytelling become an interactive, engaged participant being recited a bedtime tale personally—the events directly retold by the very actor embroiled in the tension. This allows the ongoing conflict to transpire both dramatically and theoretically as a mode of creative expression.

For example, as we witness water sprayed on the brow of the doctor to create beads of artificial sweat and see stagehands switching the props in the background of the set or moving the scaffolding and surrounding architecture, the staged quality becomes atmospherically transparent—the production design revealed before our very eyes. This simultaneity of the construction process and the final construct allows one to participate in the exigent immediacy of the story unfolding, elevating what might otherwise feel like a dated lark into the space of animated reincarnation.

Not unexpectedly, the entire scenario is a false alarm as the krait turns out to be a figment of Harry’s imagination. Beyond functioning as a humorously anticlimactic bit of situational irony, the ending doubles as a commentary on the xenophobic anxieties and hallucinations of British colonialists.

Lashing out at Dr. Ganderbai, Harry comes across as an ungrateful, egotistical jerk. His pettiness and vanity become symbolic of British rule, turning the story into a political indictment of British colonialism as an infantile, needy, and neurotic entity that relied heavily on servile Indians while treating their competence and professionalism with disrespect.

The blending of staged and actual happenings throughout Poison doubles as a reminder that history and storytelling are, first and foremost, a manipulative manifestation of the human imagination. Just as the venomous krait is sensed but not tangibly present, mythmaking is visceral and conjectural, tangible and fungible, sensory and surmised, incorporeal and real.

Whether the story or snake is actual, factual, or fabricated ultimately means little to nothing so long as it is perceived as existing. That is the terrifying power of art and imagination—it can psychosomatically affect our emotional state and waking reality while remaining a figment of the anxious, over-stimulated mind.

The Rat Catcher

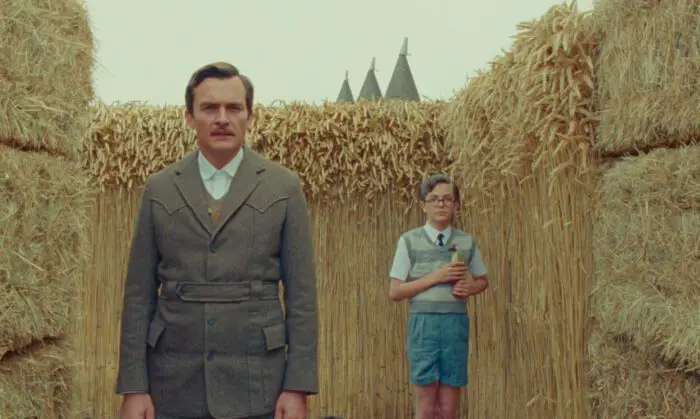

This short story—chronicling the travails of an idiosyncratic Rat Catcher (Ralph Fiennes)—is narrated by an unnamed newspaperman (Richard Ayoade). With a mixture of befuddlement and straight-faced incredulity, Ayoade spends most of the 17-minute short at the periphery of the frame, recounting the mannerisms and oddities of the Rat Catcher, who had been called in to deal with a rat infestation in a hayrick.

Ralph Fiennes is brilliantly unnerving as the titular character, personifying a rat turned incarnate. The Rat Catcher is a bizarrely garrulous fellow, rambling at length about the keys to outfoxing rats whenever on an extermination assignment. Contrary to his outspoken confidence, the Rat Catcher’s initial plan—which involves scattering poisoned oats around the hayrick—fails miserably.

Embarrassed by his professional shortcomings, the Rat Catcher flaunts his disturbing level of comfort around rats, randomly pulling a rodent out of his pocket (“I always got a rat or two about me somewhere”) and then pulling out a ferret and dropping both down the neck of his shirt. The newspaperman and his friend, Claude (Rupert Friend), witness the skirmish in the Rat Cather’s shirt with awe and horror until the scuffle eventually quiets down, and the dead rat and the bloody ferret are retrieved.

Finally, the Rat Catcher brags he can even kill a rat without using his hands, arms, legs, or feet and bets Claude a shilling to prove it. After tying the rat, the Rat Catcher leans ever closer before abruptly lunging like a snake to bite the rat dead. After collecting his money and explaining the utility of rat blood (“Penny sticks and licorice bootlaces” are made from it, he claims), the Rat Catcher scurries off, “making almost no noise” in a rat-like manner.

While the Rat Catcher is certainly a memorable character, the story is somewhat of a curio, offering little subtext or thematic weight. That said, Anderson uses the bemusedly strange and disquieting diversion to experiment with diegetic and extra-diegetic storytelling distinctions. Throughout The Rat Catcher, the narrator’s fast-spoken, diegetic interjections are sometimes acted out and sometimes merely suggested—and this fluctuation between showing and telling challenges the notions of literary and cinematic storytelling.

Conflating the two modes of storytelling by filling the screen with verbalized passages of Dahl’s text read verbatim and intermittently replacing scenes/objects with descriptions, Anderson blurs the boundaries of each medium, showing the unique ways literature/language and cinema/image can overlap and superimpose upon one another. Anderson seems to suggest that playful synthesis and dissonance between the two forms is perennially protean because language is always already cinematic, just as cinema is always already literary. Both forms may rely on varying tools and techniques and enjoy certain constraints and liberties, but they respectively serve the same essential endgame—to convey sensible sensory information.

This is not to say the two mediums are the same, either. If they were, this collection of Dahl’s shorts would be redundant. Far from tautological, the collapse of narration onto image shows us how fundamentally different each style of storytelling moves and operates. Cinema is a space where language impresses itself upon an image—even an absent or negative one. When the titular rat catcher pantomimes his rat-killing techniques, we hear the act’s description as we see its reenactment juxtaposed in real-time. It makes no difference that we can’t see a mentioned tin of poison. The gesture nonetheless lends itself to our senses, welcoming our imagination to fill in the blanks.

It is also far from superfluous to describe the rat catcher’s “crafty, toothy grin” or the way the word “rats” comes out his mouth “with a rich, fruity sound as if he were gargling with melted butter” because the effect of the characterizations as they’re performed onscreen is vastly different from the effect of the characterizations as they’re articulated textually. The image, costuming, and diegetic sound of a motion picture do one thing, while the narration’s phonetic inflections, unconventional syntactical utterances, and elaborate metaphors of the narration do another. The job of the formal artist is to understand the cumulative effects of all these narrative elements and to wield them in such a way as to create a tone, a mood, a sensation, and a text.

Wes Anderson is fully aware of this—so much so that each moment of moviemaking is brimming with the profundity and mutability of meaning and messaging. He’s at a stage in his artistry that he’s so in command of the world and story he’s constructing—a story that’s both adapted and emerging, inherited and spontaneously originating—that he deconstructs and disassembles the story while simultaneously he reconstructing and reassembling it. This kinetic duality titillates and suspends each frame in a teeming multiplicity; we see not only everything Anderson chose to include but also the periphery and possibilities he was forced, by the linear and structural confines of cinema, to elude and forego.

We see Anderson’s metatextual touch and artistry in action and his artistic object as something concurrently open and closed, infinite and entrapped, enveloping and expansive. His figurative worlds become boundlessly manifold; infinitely involuted upon themselves; creatively refractive; coherently fragmented in the chiasmic, recursive tug-and-pull between obfuscation and clarity. By winking at what is present and absent from the scene, a more totalizing synthesis and cohesion comes to fruition. We see the story’s fundamental transience and specificity and understand it as a single iteration among many potential citations, quotations, and readings.

The Swan

The Swan packs more suspense, inventiveness, and panache into 17 minutes than most feature films weave together in an hour and a half. It is a brilliantly constructed manifestation of the visual dynamism of reading—a visual audiobook simulating the imagination in motion, turning “[;p-0language into imagery. We are treated to a menagerie of stark angles, conspicuous props, diegetic costuming, staged set pieces and re-enactments, drastically varying depths of field, binocular vision, and photographic renderings of perceptual events, all combining to forge an artificially authentic composition of the mind at play.

The short story follows Peter Watson, both as a narrating adult and as a performing child, documenting the day he was harassed and bullied by Ernie and a sidekick to near-fatal degrees. With a rifle in tow, the boorish boys first tie Peter to a train track. Luckily, Peter survives by digging his feet and the back of his head into the ground far enough to avoid being hit directly. Unsatisfied, the bullies lead him to a duck pond, where they demand Peter act as a retrieving canine. Ernie soon shoots and kills a swan, and after Peter retrieves it, he cuts off the wings and ties it to Peter before demanding he climb a weeping willow tree.

On the tree, Peter is told to edge toward the end of a tree limb and then jump. Peter refuses and is shot in the leg, knocking him off balance. At least, Peter sees a bright light and flies away, becoming a swan townspeople note spotting over the village. Sustained by the willpower to live and overcome his bullies, Peter flies to his home’s backyard garden and survives.

Most of the story is told by the adult Peter standing in a corridor of towering hedges. Claustrophobic and bound by narrow margins, this establishing shot nicely reflects the linearity of language flanked by horizontal escape doors. The lane between the hedges represents the pathway of the central text, and the peripheral openings, escapades, and embellishments become emblems of the mind interpolating its meta text into the proceedings.

This primary setting resembles the nature of a written story. Whereas the text is forced to flow ever forward—like a locomotive hurtling toward a horizon point with track-bound tunnel vision—the receptive and interactive act of reading allows for tangential detours and creative pauses. By mimicking the oblique and divergent mental detours that occur while reading within the clever visual setup of The Swan, Anderson captures more than a morbid tale of boyhood sadism and resiliency—he crafts a phenomenology of literary engagement through the medium of seeing. It’s quite an aesthetic, metafictional, and cinematic feat—another indication of Anderson as contemporary cinema’s premier stylist.