Baseball is cool. It’s not for everyone, but it has a charm and excitement that has obviously connected with many people for many years. On film, there are a number of baseball classics like the Bad News Bears, Field of Dreams, and so forth. Having recently watched 42, though, something in particular struck me about the film. It did not seem like it was made by people who really cared about baseball. This might not necessarily matter. I’m reminded of how Kubrick did not think too highly of Stephen King’s prose before he made The Shining. As long as a filmmaker has a vision, they can potentially escape criticism for apathy over their subject matter.

42, however, was a bit of a breaking point. It betrayed not just a sense of apathy for the game, but also a real disinterest in its history and in Jackie Robinson himself, despite being a story, obviously, about Jackie Robinson and baseball history. It brought to mind Major League, a longtime favorite, and a film that engages with baseball with enthusiasm and love. On both a technical and narrative level, Major League is clearly made by baseball enthusiasts. From how it borrows from baseball broadcast techniques at times to the archetypes of its characters to its celebration of baseball fandom, Major League is a film that makes a case for baseball far better than 42. Putting the films in dialogue will, I think, bring to light their successes and failures, and what they say about how to put baseball on film.

42: Gleefully hollow

42 is a failure of a movie. It is maddeningly rote and hokey in its portrayal not just of baseball and its mechanics and management, but of American society in the 1940s. Chadwick Boseman’s Jackie Robinson has no real notable traits other than a supposed tendency to get heated, which the film treats as Jackie’s only trait. Robinson’s personal life is barely even touched beyond his relationship with his wife Rachel (Nicole Beharie, doing her absolute best with nothing at all) and with sportswriter Wendell Smith (André Holland, in a similar turn), but there’s nothing here that feels specific to Jackie Robinson and his story. It is all just standard fare for a film about segregation and, perhaps, for a film about segregation that was written, directed, and produced by white people.

The film’s other centerpiece is Harrison Ford’s Branch Rickey, executive of the Brooklyn Dodgers, who is easily the most valorized character in the story, going out of his way to speak out against segregation and seemingly choosing to upend the entire national league by signing a black player just on a whim. He notably says in the opening scene, “dollars aren’t black or white…they’re green,” which is a bit of a cringeworthy line, but it presents something interesting, right? Maybe there is some kind of tension between a black player striving to make it in major league baseball and set an example for future black players and a manager who is only interested in using him for profit? That might be an interesting character dynamic for 42 to pursue, so it predictably does not do that.

No, Rickey’s line is just a piece of “wisdom,” an endorsement of some kind of capitalist faux-progressiveness that 42 never challenges or unpacks in a substantive way. And Harrison Ford plays Rickey about the way you’d expect: grumbly, slow, and with no energy to be found. He’s there for a paycheck.

But is 42 at least interesting to look at? Does it tackle the challenge of presenting the game of baseball on film in an interesting way? Kind of.

42 is directed by Brian Helgeland, probably best known for A Knight’s Tale, and shot by Don Burgess, who was the director of photography on Sam Raimi’s first Spider-Man and a frequent collaborator of Robert Zemeckis. There is clearly some talent behind the camera. 42 also benefits from being a relatively modern film with studio backing and a budget in the tens of millions of dollars, allowing techniques like high frame-rates for slow motion as well as the visual work to make the film look like it takes place in the 1940s. And it does show at times, with effectively dramatic takes on plays that don’t appear in the same way in a lot of other films.

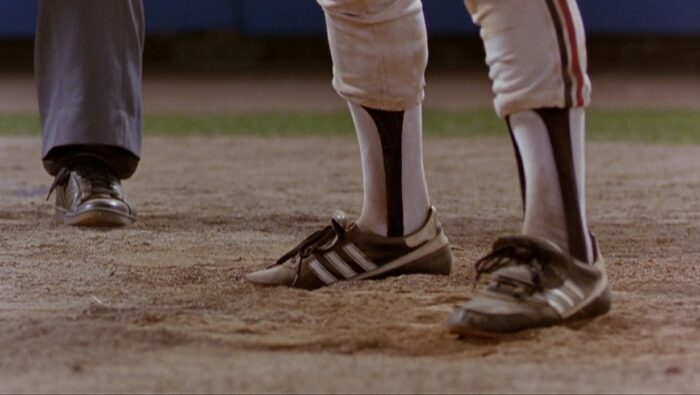

It’s these low-angle shots from the bases that stand out to me in particular. Jackie Robinson was a formidable baserunner, and he steals a lot of bases in 42, with shots like these helping highlight his speed and the excitement of the tense chase between the runner and the infield defense.

42 is definitely not the best-looking baseball film ever made, but it does show that with new technology and resources, filmmakers are capable of innovating in their approach to filming baseball. If the film’s script was even bearable or brought anything new at all to the table, it would likely be a lot more memorable and well-regarded.

Major League: The essence of baseball, for better or worse

Major League is all about the team formerly known as the Cleveland Indians. It follows the club, expected to be comfortably last place over a season that their new owner, the widow of the old owner, is trying to tank so she can move the team to Miami (This was, notably, in the 80s, before the actual Miami MLB team, the Marlins, existed). It’s got a lot of heart, and it’s a relatively ambitious project with no real main character or point of focus, aside from maybe the team’s veteran catcher Jake Taylor (Tom Berenger).

There are fun characters and a clear love and respect for baseball in Major League, which helps make up for the film’s awkward progression and its more dated aspects. The story of a small market against inept ownership and the perennially villainous Yankees is a timeless one and it works.

Major League stumbles in a way that might not be surprising: casual racism. The character of Cerrano, played by Dennis Haysbert, is a Cuban player who performs vague “Voodoo” rituals from which he supposedly gets his hitting power. It isn’t a mean-spirited portrayal, but it is certainly of its time and would not fly today.

Major League, to its credit, does a good job presenting baseball visually. The challenge of putting baseball on film is creating spatial awareness on the scale of a baseball field while simultaneously immersing the viewer on a level that cannot be done on a standard broadcast. And furthermore, while 42 is interested in Jackie Robinson and no one else on the field, Major League follows an entire team. The film contrasts extremely wide shots that show off the scale of the game and the visceral energy of the crowds with tight, intimate shots that place the viewer on the field and in the middle of the action. Take some examples:

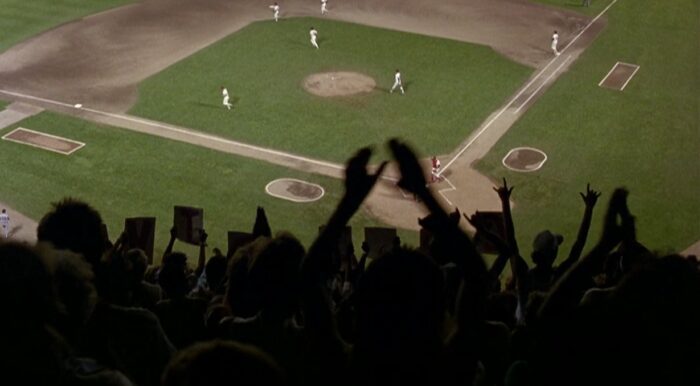

Major League often uses establishing shots like this (above) to give an extra immersive layer to the experience of the game. Baseball is slow moving at times, operating in short spurts of energy. But crowds, at least most of the time, give each game an unceasing enthusiasm and pressure, so even punctuating slower moments in the game with shots of the crowd and it’s loud, oppressive roar can keep the energy flowing.

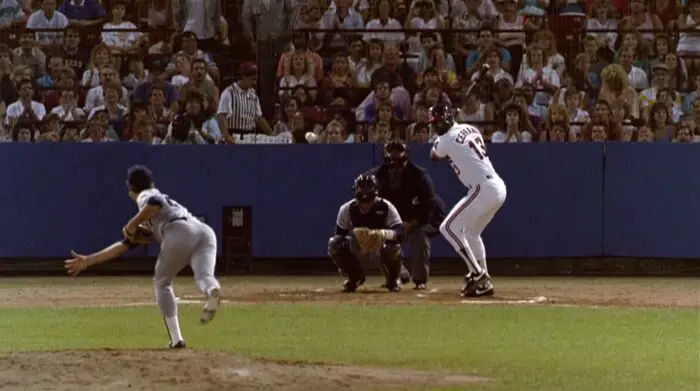

Conversely, there are also times when Major League tightens its focus and zooms in on the game at hand (above). The dramatic angles of the above shots, showing at-bats during key moments, help underscore the sneaky ways that baseball games become incredibly suspenseful. The ball is, of course, not in play during moments like these, so the filmmakers can easily keep the focus of the game on its two most important figures: pitcher and hitter. Emphasizing the batter’s features like feet, hands, and face, furthermore, give texture and help build the tension before the pitch is released.

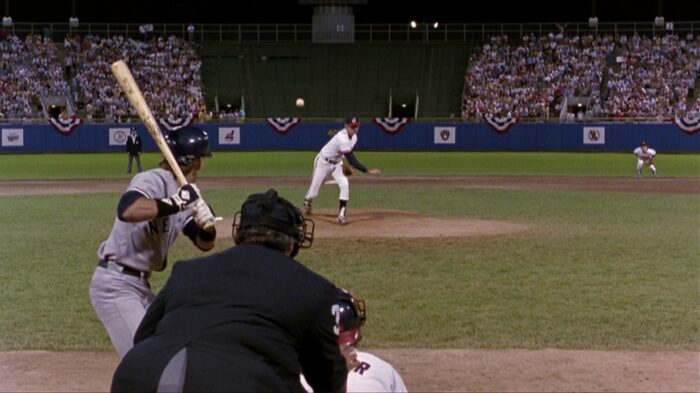

Major League also takes cues at times from baseball broadcast practices, which is often a good idea. Above shows a shot from the film that closely mimics the classic over-the-shoulder view of a pitcher, a staple of live MLB broadcasts. The film at times presents the opposite view (see below), creating a great shot-reverse shot that you could not execute in a live game.

What can we learn from this?

Baseball is fun. And when put to film, baseball and the narratives & personalities that come with it can make for great movies. However, as with anything, it takes a real interest in and appreciation for the game of baseball to make a good movie about it. There are specific narratives that come out of the experience of American baseball that are recognizable, and history often repeats itself across different teams and times. It is a game in which players and fans often have to reckon with periods of failure and simply bad play, particularly in small markets with less money to spend on high-performing players. Major League is no Bull Durham in its drama of the game, but it does deal with the internal struggles and labors of baseball players in many different ways, with characters that often reflect those that we see on the field in real life.

42, on the other hand, does not seem interested in telling a story about baseball, or really saying anything at all, other than that segregation is bad, and Jackie Robinson was good. Robinson was a trailblazer in American sports, and his story is a perfect opportunity to reckon with the history of racism in sports and the remarkable people who paved the way for non-white athletes to succeed. Instead, 42 is more interested in these cheap moments, these temporary victories, like seeing Jackie hit bombs off of a racist pitcher, or seeing his racist teammates get traded. It doesn’t want the viewer to think anything other than Jackie sure showed him!

I don’t want to argue that Major League is the best baseball movie ever (that’s probably Bull Durham, but really it’s the documentary Four Days in October). It is, as previously mentioned, dated and unfocused. What I think the comparison between these two films shows is that when a filmmaker cares about baseball, and really wants to show what they get out of it, it can make for a beautiful story and a good film. And, conversely, when a filmmaker doesn’t seem to care about baseball and its history, it shows.