October is horror-movie month, and there has never been a better time to watch the classic horror movies of Universal Pictures, the Hollywood studio most identified with the genre. Universal horror is currently streaming on NBCUniversal’s Peacock and a Universal Monsters channel has landed on Amazon’s ad-supported streaming service Freevee, available to Amazon Prime subscribers using the Prime Video smart TV app. But where to begin for the uninitiated? Are there movies outside the canon worth seeing? Scream 2 taught us that “sequels suck,” but is that true of all sequels? Fear not, children of the night. This ranked listicle in two parts will prepare you for your journey up the Borgo Pass and beyond.

1. The Karloff Frankenstein Triptych

Frankenstein (James Whale, 1931), The Bride of Frankenstein (James Whale, 1935), Son of Frankenstein (Rowland V. Lee, 1939)

If you’ve read Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (hopefully still a staple of high-school English classes) but are coming to James Whale’s Frankenstein for the first time, you may be startled by how little the film resembles the Romantic-era novel. That’s because the film is a more direct descendent of Hamilton Deane’s British theatrical production, written by Peggy Webling and first staged in 1927. Before the play was scheduled to open on Broadway in a revised version by John L. Balderston, Universal acquired the rights, hoping lightning would strike twice immediately after its success with Dracula (1931)—another monster movie adapted from a Deane stage play that Balderston had revised for Broadway.

Unlike Balderston’s version of Dracula, his Frankenstein was never performed on the U.S. stage, but it became the basis for Robert Florey’s film treatment and subsequent script, co-written with Garrett Fort (Universal eventually hired Francis Edwards Faragoh to rewrite the script and Florey never received credit for his foundational first draft). Florey was set to direct the film until Universal moved him to Murders in the Rue Morgue (1932) and hired Whale as his replacement. Whale was a gay filmmaker with an outrageously camp sensibility that he let run wild in the sequel, The Bride of Frankenstein, the finest of all Universal horror films. There, paying homage to Mary Shelley, Elsa Lanchester portrays the author in a self-reflexive prologue and then reappears in the film’s title role, wearing a Nefertiti-inspired hairstyle with white streaks zigzagging along the sides. But first thing’s first.

Consolidating several of the motifs and character types from German science-fiction films of the silent era, Frankenstein refined the iconography and formula of the 1930s monster-movie cycle as it developed within the emerging horror genre. We have the hysterically mad scientist (Colin Clive plays Dr. Frankenstein, who delivers the famous “It’s alive!” line after reanimating dead tissue), the hunchbacked assistant (played by the inimitable Dwight Frye), and the expressionistic sets (from the graveyard in the opening scene to Frankenstein’s watchtower-laboratory, equipped with all sorts of electrical gizmos, to the burning windmill besieged by angry villagers in the climax).

And, of course, there’s the monster himself. Even under Jack Pierce’s grotesque, now iconic character makeup, Boris Karloff elicits pathos from the viewer in the suffering he conveys as the Frankenstein Monster. Sure, he’s not the hyper-literate creature whom Shelley imagined in her novel, but he’s no less sensitive. Through Karloff’s performance, we see a confused, inarticulate man-child, who behaves violently by accident or provocation after his creator abandons him. Frankenstein is Universal’s first great horror film, and the studio followed it with six sequels, although Karloff hung up his boots after his third consecutive outing as the Monster. Be sure to keep watching—not only The Bride of Frankenstein, but also Son of Frankenstein—to appreciate the full range of Universal’s Gothic artistry at the studio’s creative peak in screen horror.

Horror-trivia note: Dr. Frankenstein’s hunchbacked lab assistant Fritz (Dwight Frye) is often misidentified as Ygor, but it was Bela Lugosi who first played Ygor in Son of Frankenstein. Contrary to popular memory, Ygor was a graverobber afflicted with scoliosis (not kyphosis) and served as a sidekick of sorts to the Frankenstein Monster (not as an assistant to the doctor).

2. The Invisible Man (James Whale, 1933)

People who dismiss the entirety of 1930s and 1940s horror films as outdated schlock have surely never been gobsmacked by seeing The Invisible Man, Universal’s technically ingenious adaptation of the Victorian novel by H.G. Wells. Special-effects wizard John P. Fulton relied on compositing to turn actor Claude Rains into Dr. Jack Griffin, a chemist who tests a drug on himself that renders its users invisible, while also driving them insane. To give the illusion of Griffin’s clothes floating and moving without a visible body, a scene would be shot without Rains. This same scene would then be reshot with Rains wearing a black-velvet bodysuit under his costume, covering any exposed areas of his body, against a set entirely draped in black velvet. A duplicate negative was made of the Rains footage and used to create mattes, one masking Rains and the other masking the set. Finally, the four negatives were combined for a single composite negative, and imperfections were retouched by hand, frame by frame.

Whether he’s under bandages or physically concealed by the practical effects, Rains’s performance as Griffin is one of the most memorable in the entire Universal horror catalog. In what amounts to a feat of voice acting (this was his first role in the sound era), he vividly captures the different sides of Griffin—an agent of gleeful disruption, a frightening despot in the making, and a pathetic little man—that British playwright and author R.C. Sherriff wove into his intelligent script: a story of megalomaniacal obsession in the name of scientific inquiry. Universal’s twenty-first-century update, The Invisible Man (2020), is not in the same league as the 1933 film, but it expands on the gendered implications of these themes in timely and interesting ways.

Horror-trivia note: Unlike Dracula, the Frankenstein Monster, wolf-man Larry Talbot, and the mummy Kharis, Jack Griffin had only one film to his name in Universal’s classic-era horror cycle. However, The Invisible Man spawned four sequels featuring other invisible characters: The Invisible Man Returns (1940), in which Griffin’s brother turns a falsely convicted murderer invisible; The Invisible Woman (1940), an alternate-continuity sequel and all-out comedy; Invisible Agent (1942), in which Griffin’s grandson turns himself invisible to help the Allies in World War II; and The Invisible Man’s Revenge (1944), in which the invisible man is named Robert Griffin, but whose connection to Jack Griffin is never explained.

3. The Wolf Man (George Waggner, 1941)

One of Jack Pierce’s most amazing makeup jobs was for Lon Chaney Jr. as Lawrence “Larry” Talbot, better known as “The Wolf Man.” Yet, it’s Chaney’s performance and Curt Siodmak’s script that make him such a poignant and psychologically complicated figure. The rest of the cast provides strong support: Bela Lugosi as the lupine fortune teller (named Bela!) whose bite turns Larry into a werewolf; acting teacher Maria Ouspenskaya as Bela’s wizened, sympathetic mother Maleva; Claude Rains as Larry’s estranged father Sir John; and Evelyn Ankers as Gwen, a salesclerk to whom Larry is attracted and whom he wants to protect—from himself.

Larry may be Universal’s most well-known lycanthrope, but The Wolf Man wasn’t the studio’s first werewolf film. Released in 1935, Werewolf of London starred Henry Hull as botanist Dr. Wilfred Glendon, wearing more minimalist character makeup than Chaney (think Eddie Munster). The two films are unrelated, and unless you’re a completist, you’d be better off bypassing Dr. Glendon’s lab and going straight to Talbot Castle. Neither Werewolf of London nor The Wolf Man were based on works of literature like Dracula, Frankenstein, and The Invisible Man, but The Wolf Man’s popularity with audiences inspired an industry-wide cycle of horror films about therianthropy in the 1940s.

Horror-trivia note: Universal remade The Wolf Man under the same title for a 2010 release starring Benicio del Toro as Lawrence Talbot, Anthony Hopkins as Sir John, Emily Blunt as Gwen, and Geraldine Chaplin as Maleva. A considerably more sophisticated variation on the Talbot-werewolf storyline exists in John Logan’s Showtime-Sky Atlantic series Penny Dreadful (2014-2016), starring Josh Hartnett as Lawrence Talbot, alias Ethan Chandler, a subject I have written about here.

4. The Phantom of the Opera (Rupert Julian, 1925)

Technically, The Phantom of the Opera (starring Lon Chaney Sr.) predates Universal’s turn to horror as a production category. Based on the 1910 novel by French author Gaston Leroux, it was originally marketed as another Universal “Super Jewel,” the promotional term that studio founder Carl Laemmle used to distinguish big-budget spectacles with a higher prestige factor. Phantom was a follow-up to Universal’s box-office hit The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923), an adaptation of the nineteenth-century novel by French author Victor Hugo (also starring Chaney).

Both films were clear precursors to the studio’s monster movies of the 1930s and 1940s, with Chaney—a.k.a., “The Man of a Thousand Faces”—transformed into abject figures through heavy character makeup. However, if you see only one of the two, Phantom is essential viewing. Highlights include the unmasking scene that reveals Chaney’s skull-like visage and the masquerade ball in two-strip Technicolor. Art director Charles D. Hall would later work on Dracula (1931), Frankenstein (1931), Murders in the Rue Morgue (1932), The Invisible Man (1933), The Black Cat (1934), and The Bride of Frankenstein (1935), but Phantom is no mere warmup act. It’s one of the most visually stunning achievements in U.S. cinema of the silent era.

Horror-trivia note: If you’re expecting to see the grey, half-faced base mask that has become the synecdoche for the Phantom (partly an effect of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s long-running stage musical that’s present even in contemporary adaptations), you won’t find it here. For its first three-strip Technicolor horror film, Universal remade Phantom and released it in 1943, and it was this version that introduced the Phantom’s now recognizable costume with Claude Rains in the role. Despite the lovely cinematography (the 1943 version was shot on the same sets as the original), watching the remake is a slog unless you’re in it more for the opera than the Phantom.

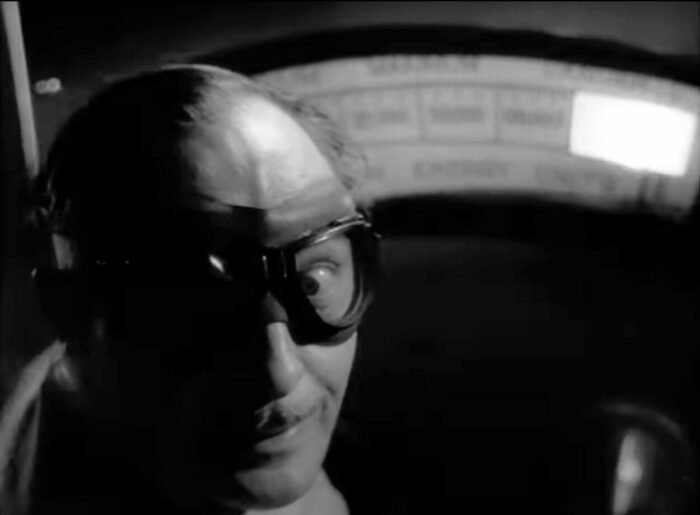

5. Man Made Monster (George Waggner, 1941)

Purists may scoff at my inclusion of this humble, relatively obscure B-picture over such fan favorites as James Whale’s The Old Dark House (1932) or Edgar G. Ulmer’s The Black Cat (1934) (don’t worry, I still like those films!), but I proudly stand by the opinion that Man Made Monster is Universal’s most underrated horror film from the classic studio period. Shot on a meager budget—even by Universal B-picture standards—and running only 60 minutes, it’s an exemplar of studio economy and efficiency, boasting some impressive special-effects given the limitations of the production. Lionel Atwill plays the screen’s definitive mad scientist: the leering, proto-fascist Dr. Paul Rigas. Lon Chaney Jr. co-stars as carnival stunt-performer “Dynamo” Dan McCormick (“The Electric Man”), whose act demonstrates his ability to withstand high-voltage electrical shocks. Conspiring to develop a legion of electrically powered supermen, Dr. Rigas makes Dan his test subject and turns him into a radiating weapon whom he is able to wield for his nefarious purposes. I would defy even the most hard-hearted of viewers not to get a little misty-eyed in the final scene, which proves how horror films can also be sad, moving melodramas.

Horror-trivia note: The junior Chaney made his horror debut in Man Made Monster. Director George Waggner, who also wrote the screenplay for the film under the pseudonym Joseph West, later produced and directed The Wolf Man (1941), the film that gave Chaney his signature role. Chaney was the only actor in the studio era to play Larry Talbot, but he also went on to play the Frankenstein Monster in The Ghost of Frankenstein (1942), Count Dracula in Son of Dracula (1943), and the mummy in The Mummy’s Tomb (1942), The Mummy’s Ghost (1944), and The Mummy’s Curse (1945).

Works Consulted

Behlmer, Rudy. Behind the Scenes: The Making Of…. Samuel French, 1990.

Berenstein, Rhona J. Attack of the Leading Ladies: Gender, Sexuality, and Spectatorship in Classic Horror Cinema. Columbia UP, 1996.

Phillips, Kendall. A Place of Darkness: The Rhetoric of Horror in Early American Cinema. U of Texas P, 2018.

Weaver, Tom, Michael Brunas, and John Brunas. Universal Horrors: The Studio’s Classic Films, 1931 – 1946. 2nd ed., McFarland, 2007.

Weaver, Tom, et al. Universal Terrors, 1951 – 1955: Eight Classic Horror and Sci-Fi Films. McFarland, 2017.