Nearly a half-century after its ending, the scarring devastation of the Vietnam War continues to penetrate souls. Representing over 16% of the soldiers drafted and 23% of the total force, Black men bore a tremendous brunt of that tragic conflict, billed by many as “a white man’s war.” Each new and old story, book, report, and testimony flesh that out in harrowing detail. The unique reverberations of the Black experience have been on prominent and topical display in 2020 with Netflix’s Da 5 Bloods, but 25 years ago, a movie went cooler, younger, and harder than Lee’s senior-citizen opus with its damaging depiction of those trying times. That film was Dead Presidents by Albert and Allen Hughes, and it deserves to be remembered and appreciated on the same level (the recent AFI Fest included the movie as a “Cinema’s Legacy” selection).

Previewing its sharpened edge immediately by showing the armed Black characters in white-painted faces, coiled in a position to strike, there is no fairytale buried treasure pipedream in Dead Presidents. The desperation and hardship are present and tangible, building to an explosive climax that can never be triumphant. There is a ballsy honesty, borrowing from comparable history, in presenting such an inevitable fall from grace.

Let me put it this way: Dead Presidents struts. Matching the descriptive definition of “walking in a proud way, with their head held high and their chest out, as if they are very important,” the different gears of their strut match the pulse of the narrative. All the while, the sinful core of pride never wavers or drops. And because it’s the Hughes brothers of Menace II Society, From Hell, and The Book of Eli, the movie seethes with splattered style to pull off those struts.

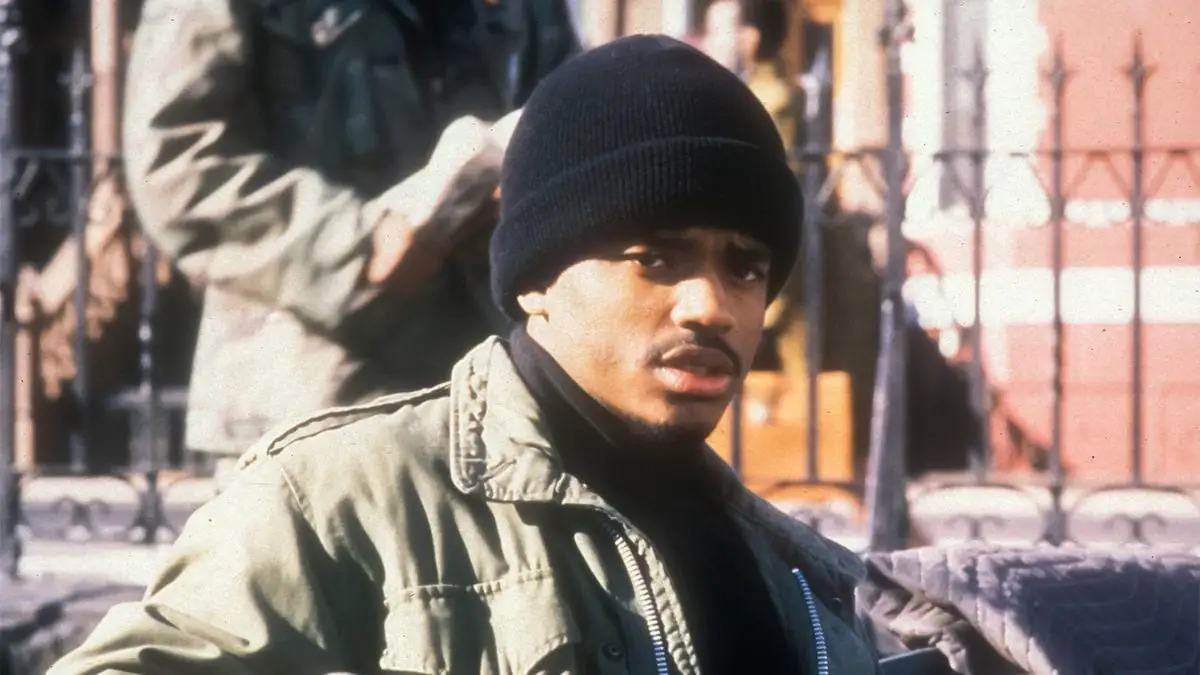

The first strut is the spry spring of youth in 1968. Anthony Curtis, played by the male Menace II Society ingenue Larenz Tate, makes his dimes in the Bronx delivering milk and running numbers for local crook Kirby (the golden-throated Keith David). He and his two close friends, wannabe pimp Skippy (a rare dramatic role for Chris Tucker, then on the cusp of Friday and Rush Hour stardom) and Latino prankster Jose (Freddy Rodriguez of Six Feet Under), are finishing high school, looking to get laid and enjoy a swingin’ summer with the Vietnam draft collecting young men his age.

With every pool game’s showy, self-pleasuring competition (one against a young Terrence Howard) and every fireside chat by way of ashtray instead of a homely hearth, the “youngblood” Anthony absorbs the nefarious little underworld Kirby brings to him. Being introduced to guns and violence on that low level matches the internal romanticism he chases for the gorgeous Juanita (Rose Jackson). Forgoing college, he readily enlists in the U.S. Marines to follow his Korean War veteran father (future Grey’s Anatomy mainstay James Pickens, Jr.).

A dash through fenced backyards after bedding his girlfriend morphs into dodging gunfire three years later in the Quang Tri jungles of Vietnam. Anthony and a reluctant Skippy are part of a recon unit led by Lt. Dugan (Jaimz Woolvett of Unforgiven), piercing threats headfirst in unprotected skirmishes. That strut has turned into one of toughness and badassery. Their ferocity—epitomized by their wildest member, an unhinged preacher’s son named Cleon (Bokeem Woodbine, at the peak of his ’90s run)—and firepower push them through the bloody barrage and the war’s end. Alive as they may be, the ordeal took its nightmare-inducing toll.

Returning home victorious as a decorated man in uniform, Anthony shifts that strut into one of smooth eagerness, thinking it’s high time he became something more respectable. He arrives back to a changing neighborhood, tough economic times, and the daughter he sired with Juanita before the war, whom he’s never met. The luster of it all wears off quickly with the question of “What did you get out of the war?” being answered by, “Not a goddamn thing.” The welcome-back hugs quickly turn into cold shoulders of employment struggles, benefit denials, and withheld compensation.

Hitting the bottle from the pressure to make money and put food on the table, Anthony’s strut turns into a sluggish one of woe. The threat of local hustler Cutty (Clifton Powell), who charms Juanita’s favor, rattles him. Entertaining contentious and communist antiwar opinions voiced by Juanita’s righteous little sister Delilah (N’Bushe Wright) clears some of the veteran’s indoctrination and incenses an urge to push back against the societal trappings holding him and his peers down. That breaking point of revolution is what brings us back to the loaded guns and foreboding face paint that opened Dead Presidents and will end it.

Dead Presidents was loosely inspired by the real-life experiences of Haywood T. Kirkland, also known as Ari S. Merretazon, chronicled in the book Bloods: An Oral History of the Vietnam War by Black Veterans edited by Wallace Terry. No matter his gait, Larenz Tate presents a lost innocence for the central composite character, swimming with all that vigor and swagger. Just 20 years old at the time, Larenz showed he was more than merely a come-hither smile. Combined with Menace II Society before this and Love Jones and Why Do Fools Fall in Love after it, the spotlight for Tate was bright for a fraction of time. Looking back now, it’s stunning he’s only had one leading film role since 2000 and has settled into TV ensembles like Power in his mid-40s.

Layer after layer of production value makes Tate and company and their struts look slick even when the gravity is grim. Cinematographer Lisa Rinzler never met a beam from an overhead incandescent bulb that she couldn’t make look ominous with ever-swirling clouds of cigarette smoke. Future MCU mainstay editor Dan Lebental deftly assembled crisp blends and cuts. The fatigues and groovy threads from costume designer and veteran wardrobe supervisor Paul A. Simmons Jr. gave all those vessels of pride flashy shells. War-sequence consultants Dan Leigh and Dale Dye would fill them with mud and sweat, and makeup head Lance Anderson would soil them with hard-R blood. Even at its dingiest, the cool factor is inescapable.

Perhaps the most robust style component of Dead Presidents is the use of music. The opening credits immediately set a tone from the Hughes brothers that is brazen and intimidating. The closeups of American cash with historical faces and places in slow-motion flames are a microcosm of this movie’s lit fuse toward greedy destruction. Establishing the mood throughout Dead Presidents is a blend of tingling percussion and echoing flute riffs from composer Danny Elfman (a mixture of instrumentation he would try again for Hulk in 2003). His score emphasizes the danger with enough snare-drum beats to cue the military undertones.

Where the score goes dark, the double-volume of song selections from music supervisor Bonnie Greenberg adds glow and gloss. The certified gold soundtrack, which topped the Billboard R&B/Hip-Hop charts and hit as high as No. 14 on the Top 200, is likely why casual audiences remember Dead Presidents. Two discs are packed with a balance of favorites and deep cuts from the likes of Isaac Hayes, Curtis Mayfield, James Brown, Jerry Butler, and more. Spin magazine named it the No. 13 soundtrack of its year, and it should have been higher.

Each song selection and placement is perfect. Whether it’s the opening bars of Sly & The Family Stone’s “If You Want Me To Stay” announcing a hot-to-trot arrival or the orchestra-backed swells of a haunting coda soaring out of Isaac Hayes’ “Walk on By,” the catalysts of emotion are gargantuan. This music is the final cadence for all of those boastful strut variations in Dead Presidents. The aural landscape propels the characters and moments of this movie at every turn. Pair this unheralded classic with Da 5 Bloods and see which hits you harder.