Sugar Hill is a sweet slice of sinister zombie horror. Though perhaps not as well-known as the blaxploitation legend Blacula (1972), it certainly shines brighter than Blackenstein (1973). This genre gem is proof that some cinema endures because it captures a vibe that doesn’t exist outside the celluloid keeping it alive.

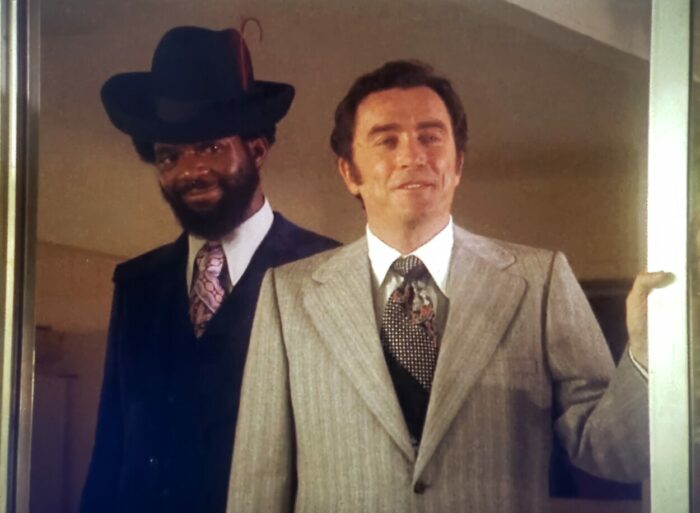

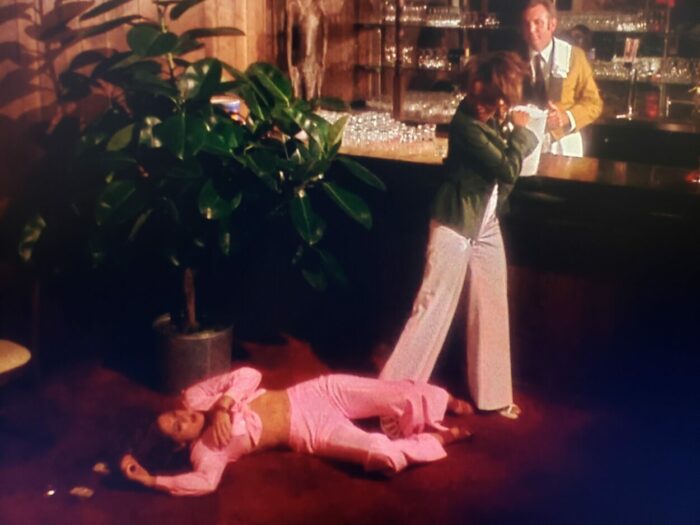

The plot follows Diana “Sugar” Hill. She’s an accomplished photographer romantically involved with Langston, owner of the popular Club Haiti. After he refuses to sell his successful joint to the mob, those same gangsters beat him to death. Vowing revenge, Sugar Hill turns to the mysterious Madam Maitresse, a voodoo practitioner who connects the vengeful lady with the lord of the dead Baron Samedi. Commanding an army of zombie hitmen, Sugar embarks on a campaign of retribution slaying mobsters mercilessly.

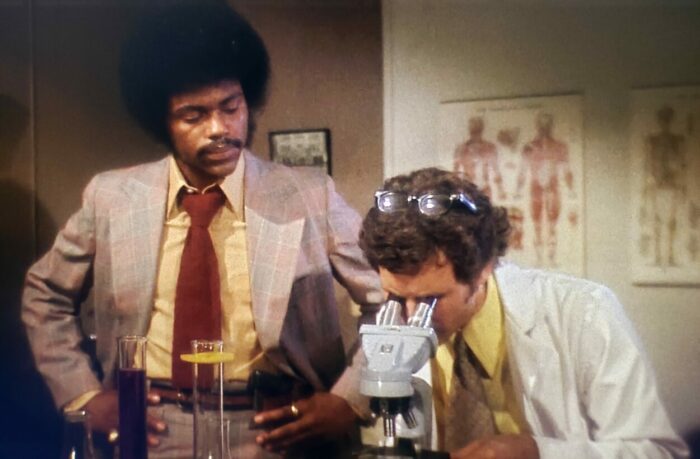

Though light on gore, Sugar Hill is nonetheless unsettling. The scene where a mob money mule gets locked in a coffin full of snakes gives me the creeps just writing about it. Plus, Sugar’s zombie legion isn’t composed of the contemporary walking dead. They harken back to more classical conceptions, closer to real zombies than the flesh-eating maniacs modern audiences expect. That’s to say, these are spellbound servants carrying out orders rather than shambling compulsive cannibals. The Sugar Hill variant are zombies who wield machetes and follow instructions. Despite having no will of their own, they aren’t witless, although they are relentlessly single-minded.

Furthermore, these zombies have their own unique look. The performers are covered in dust, dirt, and cobwebs. Pale paint decorates their bodies turning rotted flesh ashen grey. And their eyes are bulging silvery orbs without pupils. There are some fabulously chilling shots showing a mobsters’ final point of view as the zombie horde moves in for the kill, undead eyes shining in the dark.

Ann Radcliffe, who helped pioneer Gothic fiction, wrote that “terror and horror are so far opposite, that the first expands the soul, and awakens the faculties to a high degree of life; the other contracts, freezes, and nearly annihilates them.” While there’s a case to be made that both can be beneficial as far as artistic intention, it reminds that such things are unique to individual audiences. After all, what terrifies one person may make another yawn. That’s something writer James Baldwin recognized when he produced the essay “The Devil Finds Work.”

Writing about The Exorcist (1973), “Baldwin felt that it was horrific… white Americans could watch it and feel a terrified frisson, but no real fear… imagining the everyday horrors of life as a Black American… the film was a series of cheap thrills… to terrify and titillate white Americans, who would likely have little to no idea of what it was like to be treated as inhuman monsters.”

Consider how in a slasher movie white teens are happy to see the sheriff arrive on the scene. For them, there’s an immediate sense of safety in the presence of police. Yet, in a film like Get Out (2017), the mere sight of flashing cop lights implies a grim, unfair ending for Daniel Kaluuya’s protagonist.

This disconnection between what horrified white audiences and black meant that the growing cinematic landscape of blaxploitation films would naturally incorporate horror—films by black creators for black audiences. Although Junius Griffin coined the term with pejorative intent, combining the terms “black” and “exploitation” to condemn “its perpetuation of stereotypical characters often involved in criminal activity,” the genre rose. Audiences flocked to films like Shaft (1971), Across 110th Street (1972), Coffy (1973), and Dolemite (1975). Yet even the success of such crime dramas meant a hole that could only be filled by the likes of Ganja & Hess (1973), Blacula (1972), and Sugar Hill (1974).

Granted, financial success hardly allayed critics. Lerone Bennett Jr. wrote a scathing article ripping apart Melvin van Peebles’ Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song (1971), and many of his criticisms would echo throughout the prime era of blaxploitation. Writing for Ebony magazine, September 1971, he composed “The Emancipation Orgasm: Sweetback in the Wonderland.” It decries blaxploitation’s romanticization of poverty, the glorification of pimps, and the lack of focus on systemic causes behind the woes facing black Americans. The champions in such films, according to Lerone Bennett Jr., are more reactionary than revolutionary, only tackling a problem that directly affects them then winning through unrealistic individual rather than collective action.

There’s a case to be made that cinematic individuals can become inspirational folk heroes. In Super Fly (1972), Youngblood Priest, played by Ron O’Neal, defeats a group of crooked white cops. His ultimate goal being a desire to escape from a life of crime that he feels was his only option thanks to “The Man.” Pam Grier in Coffy discovers a conspiracy of corrupt local government behind the drugs poisoning her neighborhood. Through her own cleverness and a shotgun, she puts a stop to it. The victories of both individuals give, however fictional, a sense that resistance to such corruption is possible. At risk of sounding overly idealistic, stories can inspire people to greater actions.

That said, horror offered a wider door for cultural expression. The symbolic and metaphorical nature of the genre made it ideal for exploring themes directly connected to the black community. Consider, Blacula opens with Prince Mamuwalde asking Count Dracula to help him stop the slave trade. More interested in making a pass at the prince’s beautiful wife Luva, the infamous white vampire not only refuses the request but then curses Mamuwalde to eternal bloodlust. Unsubtle metaphors can still make solid points.

With Sugar Hill, filmmakers managed to combine the best and worst of blaxploitation. For instance, Marki Bey, who played the titular character, may not have the screen presence of the iconic Pam Grier, but she still manages to offer a potent portrayal. Sugar Hill isn’t a helpless damsel, she’s a successful artist who takes matters into her own hands. Yet, it isn’t she who technically accomplishes anything. Most of the voodoo manslaughter is carried out by Baron Samedi and his zombies. They may be acting on her orders, but they do all the heavy lifting leaving a sidewise sense of her relying on a man to get the job done.

This presentation of powerful women subservient to or in need of men is a common failing throughout blaxploitation. In Cleopatra Jones (1973) Tamara Dobson played a figure who could teach James Bond a thing or two. However, whenever her fiancé arrives, she practically bows, handing him the reins in situations she’s better equipped to handle. And the same goes for villains. In Truck Turner (1974), despite being a successful queenpin, Nichelle Nichols essentially begs the male criminals to handle the titular Turner, eventually giving her empire over to Yaphet Kotto so he’ll get the job done.

Aisha Staggers wrote how a lot of this had to do with studios not wanting to risk losing white suburban audiences. Even when they had every reason to be angry, portrayals of black women were modified to make them demurer.

Staggers wrote, “In the post-segregation, pro-black era, any type of character like [Cleopatra Jones] would frighten white people in the suburbs who developed an irrational fear of the black power movement,” and studios made changes to such characters to assure white audiences they were “not an angry black woman who was dangerous.”

Since part of Sugar Hill is the looming consequence of a Faustian bargain for the main character, that demurring wasn’t entirely necessary. Marki Bey could play an angry black woman frightening white moviegoers because there’s a villainous aspect to her character. In a way, horror freed the character since Sugar Hill is almost an anti-hero origin story.

Production-wise, the film is clearly low budget, though never in a way that hurts the movie. At least, no worse than Horror High (1973) or Stanley (1972). Perhaps the opening beating looks a little phony, and some effects come across cheesy. Such problems plagued a lot of blaxploitation pics without making them unwatchable. It resulted in many visual choices due to decisions being made for directors by low budget restrictions—simple camera shots, minimalist sets, etc.—things which became synonymous with the genre. So much so they left a roadmap for future films like the parodic Black Dynamite (2009).

Still, minimal aesthetics can be as much a matter of artistry as necessity. And when a film clamors for completion such stylistic choices become the expression of underlying themes however unintentionally. The low budget realm many blaxploitation films found themselves in, regardless of script quality or potential, oddly enough reflects the socioeconomic situation many black people struggle in—ignored without financial investment until larger institutions can profit off their hard work. The way big budget studios treated blaxploitation is a lot like sharks watching something appetizing starve until tenacious ambition allows it to fatten into prey worth eating. Case in point, films like Car Wash (1976) which grew out of the genre once big money could be grabbed. Whatever other elements are present, “political exhaustion and economic recession are never far.” Notions better explored in “The Badasssss and Avante-Garde: The Radical Aesthetics and Politics of Melvin van Peebles” by Samuel Smucker.

Sugar Hill is essentially about a black man murdered because he won’t hand over his business to corrupt white people. Unable to get justice through the system, his lover turns to voodoo. The zombies she utilizes still wear slave shackles which is truly tragic since they’ve basically never escaped bondage. Yet, they become tools in service to the slaughter of racists. Overall, it’s a film about a powerful black person who can’t trust the white system to help her, so she turns to her own people, in a way her cultural heritage, to get revenge.

Some skin scenes get into the picture as well. Sugar Hill’s job as a photographer offered an excuse to get bikini models on camera for no real reason. Still, it arguably helps show the character as independent and successful on her own. Without straying into sleazily gratuitous, it’s that best and worst of the genre coming together.

The persistence of blaxploitation may very well speak to the lack of representation in Hollywood. These artifacts of the era are in their own way uniquely historic. Prior to the 1970s, the only fully African American film production came out of the Lincoln Motion Picture Company. Founded by Oscar Micheaux in the 1930s, they made movies like Within Our Gates (1920) which challenged racist stereotypes in features like The Birth of a Nation (1915).

“Throughout the first half of the 20th century Micheaux depicted contemporary Black life and complex characters in his films, countering the negative on-screen portrayal of Blacks at the time.”

Filmmakers like Melvin van Peebles may have intended to do the same. How well they succeeded remains a matter of debate with contemporary critics like Cedric Robinson echoing Lerone Bennett Jr. But even an imperfect portrait is a picture worth a thousand words. While blaxploitation pioneers may have sought to glorify black culture, cinematic depictions risk solidifying negative notions. Unaware of a portrait’s missing portions, white audiences may mistake romanticized fiction as nearly truth. However, horror films like Sugar Hill automatically imply artistic liberties due to an inherent detachment from reality.

Amalgamating Baldwin’s observations with Radcliffe’s, if white audiences could cinematically experience the terror black viewers did, it might expand their appreciation of African American adversities. Similarly, if some horror froze both peoples to the core, it might reveal certain unspoken understandings and connection. That may have been one of the arguable intentions of the 2021 Candyman remake. And there’s a loose thread connecting such films with the blaxploitation horror of the 1970s.

As fiction, Sugar Hill allowed for a supernatural solution to a broken system. That brief relief from a reality without such an option can’t be undersold. Even if imperfect, Sugar Hill embraced pro-black themes, while scaring some appreciation for that culture into white audiences. And fifty years later, people are still watching.