The Human Adventure Is Just Beginning.

That was how Star Trek: The Motion Picture ends and how a new era of cinematic exploration would begin. In 1977, George Lucas brought us Star Wars. In response, Gene Roddenberry decided to resurrect his initially unsuccessful 1960s science-fiction television show Star Trek, which had recently been brought to new and vibrant life in the seventies thanks to the emergence of fan conventions and the television re-run, to the big screen in 1979. But where Lucas focused on the myth and magic of space adventure, Roddenberry aimed for the mystery and philosophy of space exploration. Star Wars displayed the how, Star Trek explained the why.

Needless to say, the slow-moving Star Trek: The Motion Picture, debuting in theaters in 1979 did little to enthuse those with a thirst for wall-to-wall action as Lucas had provided. A precedent had been set by Lucas and space adventures were to abandon the meandering, philosophical mystery of something like 2001: A Space Odyssey and instead provide a sense of mythic adventure; classic tales of heroes in shiny armor and villains with black hats with the fate of the universe at their fingertips thanks to mind-shatteringly powerful technology.

Staying true to the introspective nature of the television show where Captain James T. Kirk (William Shatner), Science Officer Spock (Leonard Nimoy), Chief Medical Officer Leonard “Bones” McCoy (DeForest Kelley) and the rest of the intrepid crew sought answers from within to solve their biggest adversaries. Star Trek: The Motion Picture still provided audiences a universe-threatening weapon of mass destruction but instead of fighting it with fists, phasers, and torpedoes, they reasoned with it; challenged it with logic and thought. For those expecting a large world-annihilating laser base to be destroyed with zero seconds left on the clock thanks to some lucky torpedoes, they were sadly disappointed.

Despite being the fifth highest-grossing film of 1979 ahead of such films as Alien, 10, Moonraker, and The Muppet Movie, the first Trek picture earned derogatory names like “The Motionless Picture” or “The Motion Sickness”. And while technical aspects, even to this day, are praised, including the Oscar-nominated Visual Effects, Art Direction and (exquisite, this author must add) Original Score by Jerry Goldsmith, fans are quick to put this into the Evens-Odds sequence of Trek films, the long-held fan narrative that odd-numbered Trek films are “bad” and even-numbered Trek films are “good”.

To weigh in on this, I recruited the help of some Trek experts. Ben Cahlamer, a film critic for The Movie Revue, doesn’t necessarily believe in the even-odd theory himself saying, “I don’t fall into the odd-even camp. Each successive movie has its merits; every story does. With The Motion Picture, it has taken me over 35 years to get its inner meaning, but other than falling asleep in the theater when I was three, I knew that there was something more to the film.” Cahlamer sees the film’s inaction as one of its strengths, pointing out that the film “isn’t a character study” and that “the challenge with the film is that it is not full of action or excitement…[it] is a study in shades of grey and static acting”.

Theatre critic and self-described “nerd” Neil Shurley elaborates on The Motion Picture’s excitement level, stating the film “always resonated with me because of the sense of awe”. He adds, “As much as I loved Star Wars—because, come on, STAR WARS!—I enjoyed the more deliberate pace and sense of wonder…there’s something transporting and reflective about the whole experience”. Unlike Cahlamer, Shurley does feel the film is character-based, most especially in regards to Spock.

The Motion Picture, regardless of where it stands on the character-study level with critics and fans, does little to differentiate itself from the television show it is based on. Save for a few expository references to what the crew has been up to for the last four (plot) years since we last saw them, the movie functions much like an episode of the show. It assumes you know who is who and what they do and spends little time digging deep into the who, what, and why they are, with the exception of perhaps Spock, whose identity crisis as a half-human/half-Vulcan becomes a core part of the story.

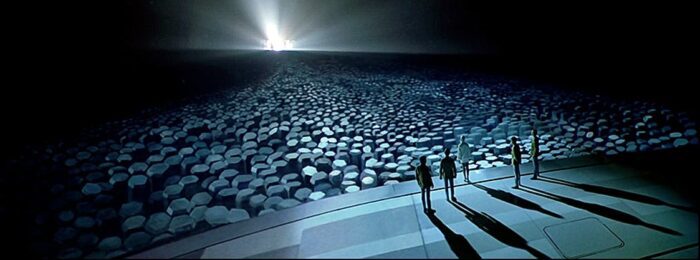

The film’s plot centers around a massive cloud that is approaching Earth. It devours everything in its path including three Klingon cruisers who barely put up a fight. The newly refitted, but barely functioning, starship Enterprise—captained, at least initially, by William Decker (Stephen Collins)—is sent to intercept it and make contact with the hope of avoiding an incident. However, before its initial cruise, Admiral James Kirk demands he take command of the mission and the ship and demotes Decker to executive officer. Joining Kirk are his old crewmates, chief engineer “Scotty” (James Doohan), Navigator Sulu (George Takei), communications officer Uhura (Nichelle Nichols), and tactical officer Checkov (Walter Koenig). An old flame of Decker’s, a Deltan named Ilia (Persis Khambatta) joins the crew as a helmsman on the maiden voyage as well.

After reassembling some of his former crew who had retired, like Doctor “Bones” McCoy, and science officer Spock, who had attempted, and failed, to achieve the Vulcan right of passage Kolinahr (the shedding of all emotion; something Spock must doubly work for as he is half-human) the Enterprise sets forth on its mission. The Enterprise soon discovers the cloud contains a massive machine-like being of infinite power that can destroy “carbon-based units” it sees as infestations of machine purity. This being, named V’Ger, seeks its creator, which apparently inhabits the Earth. When “the creator” does not answer V’Ger’s calls, Kirk, Spock, and the crew must not only determine who the creator is but how to communicate to the superstructure that humanity is not an infestation to be washed away.

While Star Wars dealt with a more wide-ranging mysticism like The Force, Star Trek has often dealt with issues of creation and godliness, often having it face head-on with science. The Motion Picture’s dual looks at the origin of a species (V’Ger’s creator and Spock’s human side) tap into the deep philosophical and theological themes that generally turn off a pop culture audience, which may account for some of The Motion Picture’s detractors. On one level, it is a thinking man’s picture and not to belittle a massive audience out there but many go to the movies for escapism, not lectures.

But on another level, in a lot of countries where God is the center of people’s lives, Star Trek’s borderline agnostic approach to deities, seen as flawed creatures defeated by science or simply accidents of nature that are, thus, explained by nature and not by blind faith, can be off-putting. The Motion Picture has two beings searching for meaning: V’Ger, which seeks its creator and Spock, who seeks to understand why his human side demands so much attention and emotion when his Vulcan side calls to him to abandon such things. By the film’s end, both reach conclusions on the why and it isn’t ambiguous, rather, it is cut and dry.

Spock, as Shurley states, “has always been a man divided, trying to reconcile his human and Vulcan halves. In the beginning, he is on the verge of purging emotions completely, of fully embracing his Vulcan heritage. But his encounter with V’ger finally makes him learn the importance of connection, of humanity.” Spock’s arc is thus resolved rather completely and its resolution “is a lesson that fully informs [him] for the rest of his life.”

V’Ger’s more outward goal of seeking its creator proves to be weighty, and theological, material. And while some see Star Trek as agnostic at the least and atheist at the most, film critic Cahlamer sees it slightly differently. “In The Motion Picture, there is contention to support belief in a higher being, but it is being questioned by V’Ger, which could support a claim of agnosticism without knowing that there is more knowledge. The Motion Picture has a very cynical view of religion, but it does not deny its existence.” Cynical might be the most refined way to look at Trek’s view of religion as Cahlamer states. It doesn’t flat out deny it’s existence but, perhaps like Agent Dana Scully, it always has some rational explanation handy even in the most extreme of situations.

Outside of the religious sphere, The Motion Picture also touches on man’s reliance on and fascination with technology, depicting a world constantly in flux with the wonderful creations man has put in the universe, almost to the point of its own irrelevancy. All-powerful machines are not new to Star Trek. In Kirk’s time, he’s battled with computers-gone-mad like Nomad, the M5 Multitronic Unit, and the Doomsday Machine! But The Motion Picture offers its own, more personal take on tech, sometimes going philosophical.

“Trek works best when it doesn’t overthink its technology and puts a human element to that tech. Without that human touch, though, we can never improve beyond our place today, ” says Cahlamer. The Motion Picture is loaded with technology with human failings: transporters that don’t work quite right, engines that are just out of tune, a ship a few hours away from being ready. Oh, and not to mention a satellite that was launched into space that has returned home and gained sentience! But there is also an obsession with this technology that drives not only humanity on the macro-scale but Kirk on the micro-scale.

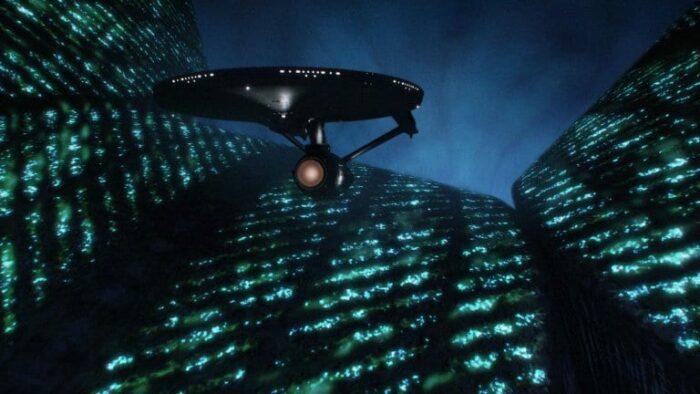

Kirk’s relationship with his own ship, The Enterprise, his obsession, is mapped directly to his character’s journey. As Shurley states, “Kirk…gets answers to his search for his own meaning – learning that (to steal a quote from his own future) captaining a starship is his first, best destiny.” The Motion Picture shows Kirk’s idolization of his ship with a multi-minute sequence of he and Scotty approaching the ship in dry-dock all to the grand flourishes of Jerry Goldsmith’s score.

But it returns to that human element Cahlamer raised. The Enterprise, in itself, becomes a character just like V’Ger, also an inanimate object, becomes one. As Shurley added about the Enterprises’ own character journey, “the Enterprise also gets its own arc by starting out not quite ready and finishing as the SHINING GODDESS OF SPACE, THE GREATEST SPACESHIP OF ALL TIME,” adding humorously, “There is no comparison”.

There would never be another Star Trek movie like The Motion Picture. Despite its commercial success, the budget had ballooned on the picture and Paramount did not want to spend the kind of money it did on a Star Trek II that it did with their first attempt. In a sense, though never outright cheaply made, all future Star Trek films would be shot more like genre films: lower budgets with re-used sets and cost-cutting measures meant to maximize the box office take. By the time the successful series was on its sixth film, raking in hundreds of millions for the studio, Paramount was still only letting Kirk and crew use redressed sets from The Next Generation.

The Motion Picture was made with grandeur and an old Hollywood feel: the sets were ginormous and expansive, the visual effects awe-inspiring and epic, and the depiction of space dark and mysterious, filled with depth and breadth, something the television show it was based on could only dream of doing in the 1960s. It was a gamble too, but one that paid off but apparently wasn’t worth trying again. At least in the same way.

Because a few short years later, Kirk and crew would be back doing battle with one of their greatest enemies…you know him as Khan. See you in a few weeks.