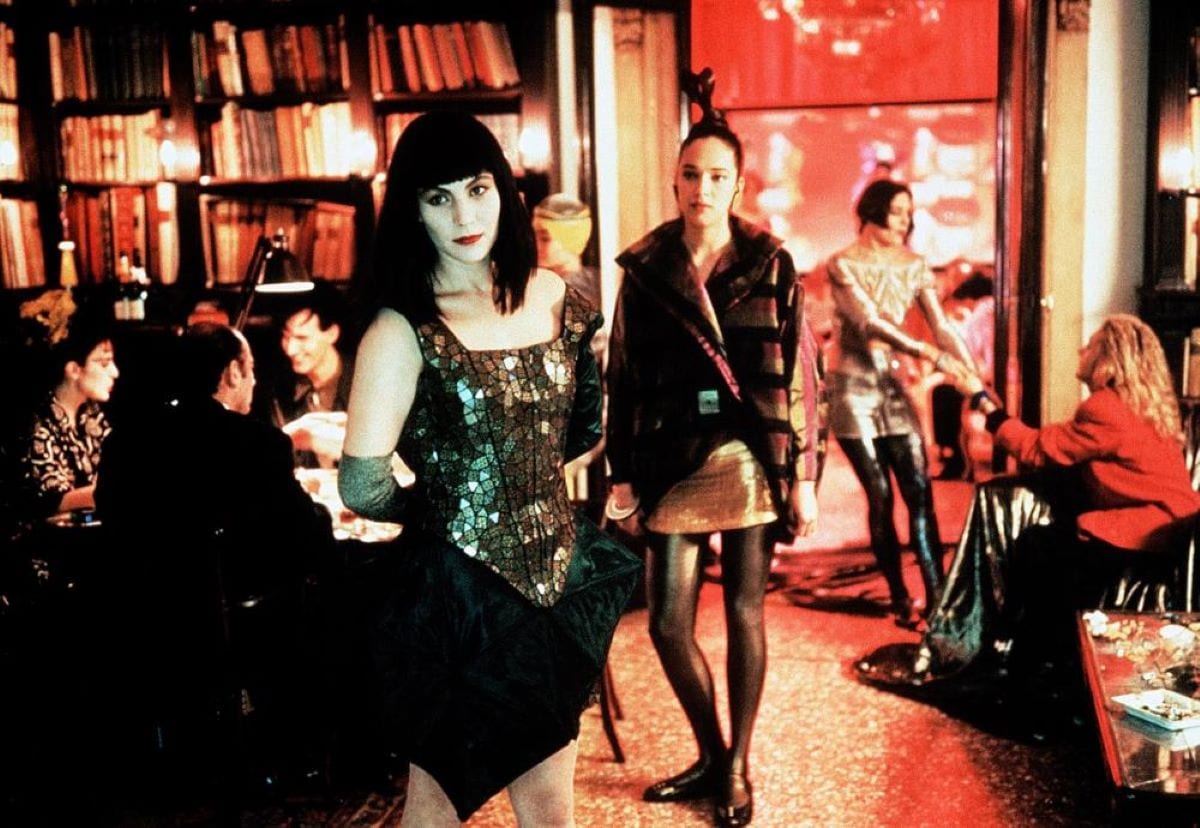

In Wim Wenders’ epic 1991 film it is the year 1999, the world is on the edge of a knife as a rogue nuclear satellite is going to crash to the earth any minute, and potentially take civilization with it. Amidst this chaos, we meet Claire (Solveig Dommartin). She is reeling from the infidelity of her partner Eugene (Sam Neill) and is drifting around Europe in a haze of drinking and brief encounters on a vapid party scene. While caught in a traffic jam and feeling bored, Claire ends up inadvertently assisting some bank robbers in transporting their stolen loot to Paris. Along the way she meets Trevor McPhee (William Hurt) a mysterious man who is being pursued by some shady secret agent types.

When Claire is reunited with Eugene in Paris, she discovers Trevor has stolen some of the money she was carrying. Claire pursues Trevor with the help and hindrance of a private detective, as well as the lovesick Eugene. She discovers in Moscow that Trevor is really Sam Farber, a man who has stolen the prototype for some revolutionary technology and is being pursued by government agencies and corporate bounty hunters. The journey moves across China and Japan, before ending up in Australia where Claire, Eugene and Sam are all reunited at Sam’s father’s laboratory in the outback, and they learn just how world-changing and potentially dangerous Henry Farber’s coveted invention could be.

The idea behind Wim Wender’s Until the End of the World was to create “the ultimate road movie”, and it was initially released in a 158-minute cut in 1991 that flopped at the box office. It was something that Wenders had been keen on since 1977, but had to wait until he had a few solid hits under his belt so he could attempt what would be his most ambitious work. The film was shot across 11 countries and was financed by several European and Australian production companies. A 5-hour version was shot and edited down from an initial 20-hour long cut. This version screened a few times to a better reception overall, and various versions of differing lengths were available in Japan, Germany, and France. The director’s full 5-hour version first screened in 2015 is now available from Criterion in a two-disc Blu-ray that was released late in 2019.

Essentially the story revolves around three characters. You have Claire who is something of a dreamer, a bit impulsive, and a bit desperate for something to shake her out of her sense of betrayal and malaise. Then you have Eugene, a writer, filled with regret and borderline obsession over the love he lost and willing to do anything to get it back. You get the sense that Eugene sees Claire almost as a case study, and the basis for a future novel, the content of which informs the voice-over throughout the film. Finally, you have Trevor/Sam, a man with some serious father issues as well as failing eyesight who attracts Claire and eventually falls in love with her, though he feels it may well be doomed. The cyberpunk style corporate espionage and technology is just icing on the substantial cake of character work that this road trip offers.

Back in 1991, there was very little green screen in film making outside of sci-fi blockbusters. It was available, but it was limited, and film productions had to rely more on actual real-world locations than the world’s they could imagine with unlimited funds. It was also a time before the proliferation of CGI, Terminator 2 (1991) had only just come out and revolutionized effects-heavy movie making, but its full impact wouldn’t be felt until Jurassic Park two years later in 1993. Wim Wenders and his production crew in the early ’90s trotted the globe more than a typical James Bond production. The film takes in locations in Berlin, Paris, Moscow, China, Japan and Australia, and many others. They sought out locations that would give you the idea that this takes place just a little way into a doomed future, but Wenders and cinematographer Robby Muller make sure the audience is as transported as the characters, with claustrophobic capsule hotels, cluttered streets, slums, downmarket shopping malls, and finally the stunning wide-open vistas of the Australian outback.

Wenders was also ahead of the curve in terms of movie soundtracks at the time. You could argue that it wasn’t until The Crow in 1994 that the movie tie in soundtrack album really became big business, but in 1991 Wenders chose an eclectic group of artists from U2 to Neneh Cherry, to R.E.M and Julee Cruise, and the soon to break up Talking Heads. It wasn’t just on the CD release either; all these songs make their way into the film to underscore the emotions, the character journeys, and the atmosphere of a world nearing collapse. It is perhaps one of the best examples of astute soundtrack choices before the soundtrack became just another marketing gimmick.

1992 was the year that my film fandom blossomed from casual pastime to full-blown obsession, and so I had heard of Until the End of the World thanks to my ravenous reading of the film magazines of the time. After the film died at the US box office on only four screens, we finally got a home video release in late 1992 with cover art that suggested a Blade Runner (1982) riff which it turns out was massively misleading. The VHS release was of course pan and scan, and the truncated version of the film didn’t really do the concept or the actual film any favours. I was disappointed by that initial version, but something about that film stayed with me. I would watch it again on DVD about 18 years later, and what had stayed with that 14-year-old boy now hit the 32-year-old man in a whole new way. The film, even in its truncated form, was close to a masterpiece.

I always thought I would be game for the 5-hour version of Wim Wenders magnum opus. So with Criterion Blu-Ray in hand, one January evening in early 2020—just before ironically a super virus and what was predicted to be the end of the world—I sat down and consumed the whole thing in one sitting. The first thing is that in its proper aspect ratio, in HD, and on a 4k TV, Until the End of the World is gorgeous to look at. The second thing is how essential all the material they cut out feels in its 5-hour version.

Surprisingly for a film with such a monumental running time, I never once felt bored, checked my phone or was anything other than absorbed. The characters are more fleshed out, the whole diversion with the bank robbery makes more sense, and you get more of a sense of who these people are. Eugene and Claire’s relationship is better defined, you get the sense of loss between them, and what drives Eugene to follow Claire as she pursues Trevor/Sam. You also get a greater sense of Trevor/Sam as played by William Hurt, beyond him being a handsome mystery man. As a result, the final hour and a half have much more of an impact as you see these characters ravaged by their obsessions and failures. In the original cut, it feels as if there were a whole couple of countries missing. I don’t remember spending anywhere near as much time in China and Japan as there was here, and the Japan sequence, in particular, feels vital to everything that follows with the extended and fleshed out time spent in the desert cult formed around Henry Farber and his experiments.

It’s very rare that science fiction cinema made decades ago becomes somewhat of a fulfilled prophecy. The closest recent example I can think of is Kathryn Bigelow’s Strange Days (1995) which predicted not only a frightening dip in race relations but also POV camera technology used for human gratification. Where Until the End of the World becomes eerily prophetic is in its final act.

As we get closer to Australia and Henry Farber’s outback laboratory nestled deep within a cave, it becomes apparent that the device Sam is smuggling is something that enables the blind to see. Through testing on Sam’s ailing mother, it turns out that the device has an alternate application. It becomes something with which human beings are able to record their dreams and memories. This footage (the first film to use actual HD footage) is distorted and elusive, always just about to show some kind of truth and then distorting further and slipping away. When Sam’s mother dies, this new application becomes an obsession for his father, and in turn Sam, and then Claire. As they lose themselves further and further, abandoned by those that gathered around their genius, they stare red-eyed and almost catatonic at the small handheld devices replaying their own dreams back at them. It ultimately drives Sam and Claire apart; they end up preferring the company of these new devices rather than each other.

Wenders had in the early part of the film, already shown us something accurate in terms of how car-based satellite navigation systems would eventually work. But by the finale, he has shown us where our society was headed. Mobile phones went from a convenient tool to an out and out obsession in the last twenty years. They hold a lot of our dreams, our memories, and our fears, and we refer to them frequently as if looking for validation and justification that we exist. As Sam and Claire stare at these portable devices, it’s reminiscent of the way in which the populace refreshes their social media feeds over and over, looking for that justification, that acknowledgement that they are real and people care. Their relationship collapses, just as divorce rates went up with the advent of Facebook. When Eugene finally forces Claire to go cold turkey, or the battery dies on her device, it’s easy to see the reaction as that of a bullied teenager made to give up the damage that social media has done to her sense of self, or the person desperate for that return text when technology inevitably fails.

We have also had before this prophetic climax, a future world where individuals were able to be located via digital footprints, and what the internet search engines may eventually look like. The films framing device with regards to an Indian satellite seems to predict the fears that we had with regards to a Y2K bug plunging us all back to the stone age. When the satellite finally hits, it is in a beautiful sequence with a plane losing power over the desert and gliding with Sam and Claire to an uncertain fate. It is a scene that perhaps encompasses all of the themes of Until the End of the World, humanity gliding through life with technology and connections we are barely able to comprehend or stop ourselves from becoming reliant on.

Until the End of the World is the kind of film that just doesn’t get made anymore, the kind of personal, epic, multi-continent jaunt that went out of favour a long time ago. On paper, it’s something that shouldn’t work, but in this 5-hour version its blend of tech-noir, spy games, romantic farce, and road movie comes full circle, and gels into a genuine masterpiece. The length may put off some, but for fans of real cinema, it’s a journey well worth taking.

Great essay. I totally share your love for this film!

I forgot how much I love this movie. Thanks for reminding me. I just signed up for the Criterion streaming service–cancelled Netflix to pay for it and feel purified for leaving all the Tiger Kings behind.

(Also, it looks like you and I are working on the same novel, but I’ve been writing mine for over twenty-five years. :D)