Despite coming at the tail end of the film noir era, Blast of Silence (1961) is one of the bluntest and most stylistic examples of the genre. Written, directed, and starring Allen Baron, Blast of Silence tells the story of a doomed hitman named Frankie Bono (Baron). After being orphaned at a young age, Frankie comes back to New York City from Cleveland to take out a boss named Troiano. Along the way, he reconnects with a childhood friend and his sister Lori. The hit starts to go awry after his contact to buy a gun, Big Ralph (Larry Tucker, who steals every scene he’s in), recognizes Frankie’s target and tries to shake him down for more money. After being forced into murdering Ralph and getting rejected by Lori, Frankie’s loneliness starts to get the better of him and he becomes increasingly erratic. He completes the contract, but his employers still decide to take him out, and Frankie dies alone in the marshes.

From the outset, the audience is treated to some of the most delightfully over-the-top noir narration I’ve ever experienced. The opening lines of the movie not only set the tone for the narration, they set the stage for Frankie’s entire life: “[r]emembering, out of the black silence, you were born in pain […] you were born with hate and anger built in, took a slap to the backside to blast out the scream, and then you knew you were alive.” The opening narration tells the story of Frankie’s birth, his mother’s death during childbirth, and the pain and loneliness that he has been carrying with him since his earliest moments.

The narration—accompanied by the bloodcurdling screams of Frankie’s dying mother—occurs over a mostly black screen. Initially, the only variance in the darkness is a small white dot that dances across the screen. As the scene goes on, the dot grows until it becomes apparent that it is a literal “light at the end of a tunnel” captured by fixing the camera onto the front of a train. When accompanied by the opening narration recounting Frankie’s delivery, this universal metaphor for death also invokes images of birth, as if the train is emerging from a womb. I think that an argument can be made that during his death scene, as Frankie tries to claw his way out of the marsh covered from head-to-toe in viscous mud, can be viewed as womb or birth imagery as well. For Frankie, life and death have always been one and the same.

Furthermore, the train’s emergence from the tunnel hits the audience with light and sound: after being in the dark for almost a full minute, the explosion of light that accompanies the train’s emergence is a shock to the audience’s system. The moment is accompanied by a cymbal crash, which audibly accentuates and literalizes the visual “blast.” The sudden assault of light and sound instills into the audience the same confusion and disorientation that Frankie felt during much of his unmoored life.

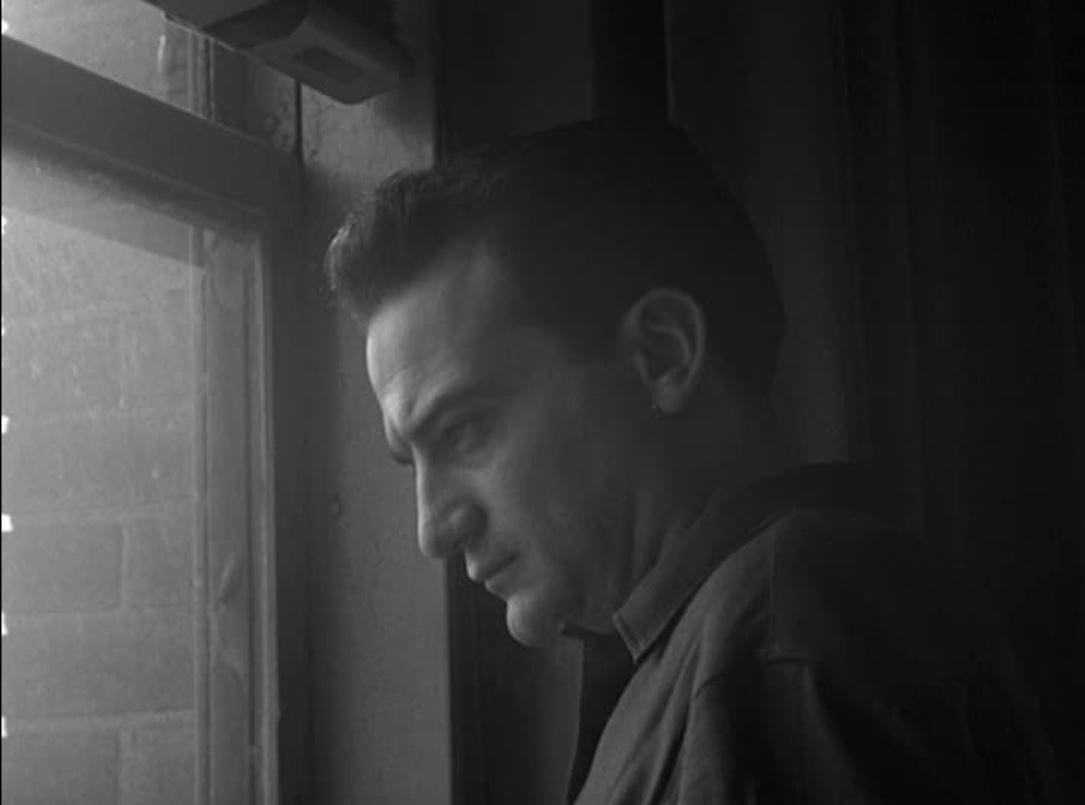

Despite being an effective film noir, the film also subverts numerous noir conventions. The outward trappings of the noir protagonist are present—the trench coat, fedora, and no-nonsense attitude—but Frankie doesn’t remotely resemble the smooth, fast-talking, Humphrey Bogart-type of man that usually served as the genre’s protagonist. While the narration that serves as Frankie’s inner monologue has plenty to say, Frankie himself says very little. The narration, which is delivered by a different actor (Lionel Standler), projects the image of the more prototypical noir lead, in contradiction to the reality of Frankie’s character. The quality of Standler’s voice is much different than Baron’s; Richard Brody perfectly describes the voice as “graveled,” while Baron’s voice comes across much more high and weaselly.

Casting a different actor to deliver the narration emphasizes the disconnect between Frankie’s self-perception and actual character: he may view himself as a more archetypal noir character, but in reality, he’s weak, broken, and pathetic. Moreover, the narration is delivered in the second person, further alienating the audience from Frankie’s point-of-view. Frankie’s narration tells us that he has “always been alone. By now it’s your trademark. You like it that way,” but there is plenty of evidence that tells us that he does not like to be alone. As the movie progresses and Frankie’s alienation worsens, the notion he has of himself as a god when he is stalking his target (“You get a feeling this is how it was meant to be. Like you are Troiano’s fate. Like you’re God.”) is laughable in comparison with his interactions with other characters, especially Lori.

Lori subverts the familiar femme fatale trope that is common in noirs. While she is flirty with Frankie, she rejects his advances and actually lives a normal and apparently monogamous life with her boyfriend. The scene when she rejects initially unfolds like a similar scene in Blade Runner 20 years later, although I doubt that Blast of Silence had a direct impact on the later sci-fi neo-noir classic due to its relative obscurity at the time and different end result.

The scene in Blade Runner has become a central sticking point when discussing the film and its legacy, including here on 25yl. It could be easily argued that the actions of the leading men of both films constitute sexual assault, especially in Blade Runner where there is an added layer of power imbalance due to Rachael’s recent revelation that she is a replicant. But where Sean Young’s Rachael eventually (and perhaps unwillingly) cedes to Harrison Ford’s Decker, Lori rejects Frankie and asks him to leave while he grovels and desperately pleads for her forgiveness. I was surprised that the way Blast of Silence handled the scene felt surprisingly mature and is certainly less off-putting than in Blade Runner. The scene isn’t meant to be romantic or titillating: the protagonist is rightfully rejected and ceases his actions. It also dispels any remaining illusions the audience held about Frankie: he is not strong and slick but is instead weak, insecure, and lonely. Blast of Silence’s treatment of this scenario struck me as being much more well-handled and borderline progressive for its time, certainly within a male-dominated media landscape that was much more inclined to present the Blade Runner version of the scene.

The film’s Christmas setting plays a major role in the film. Once again, the film’s narration and images belie Frankie’s actual feelings of insecurity. While Frankie ostensibly claims to despise the holiday from the film’s earliest moments—the opening credits are still rolling when his narration states that “[t]he railroad company makes sure you don’t forget you’re coming to town on Christmas. Gives you the creeps. You hate cities, especially at Christmas”—he seems inexorably drawn to it. At points in the film he stops in front of a sidewalk Santa, goes to see the Rockefeller Center Christmas, and stops in front of a Kress storefront with toys and Christmas tree lights in the window.

The sequences in Rockefeller Center are among the most iconic in the film. Frankie pretends to ignore the tree as he walks by, outwardly projecting a hard exterior without ever even acknowledging its existence. The bustle of people around him and the prominence of the tree means that he almost certainly has to be purposefully ignoring it. But then why not avoid the tree altogether? It’s a big city and he’s not headed anywhere in particular during these moments, he’s just aimlessly wandering. His faux avoidance of the tree is exposed as he goes to the tree again later in the film, this time walking much closer to it. This time, he subtly sneaks in a glance.

The narration helps to explain Frankie’s simultaneous rejection of and fascination with Christmas:

Funny, your hands are cold when you think of Christmas. Remembering…remembering other Christmases. Pushing your nose against the plate glass store windows until the cold of it made your head ache. Wishing for something. What was it? Roller skates? Bike? Sled? Games? Nothing like that. Something bigger, more important. Something special.

To Frankie, Christmas represents everything that he missed out on as an orphan, but also everything that could have been. It is paradoxically a reminder that he went down the wrong path while also being a source of hope for him that things might get better: that he can settle down, retire from contract killing, and start a family. In his dying moments, Frankie’s narration implies that he longed for his own death for all those years (“[r]emembering other Christmases wishing for something, something important, something special. And this is it, baby boy Frankie Bono. You’re alone now, all alone. The scream is dead. There’s no pain. You’re home again. Back in the cold black silence.”), but we’ve seen over the course of the movie that this isn’t the case.

There’s a moment midway through the film where Frankie attends a party with Lori’s brother Petey. At one point, Petey stops the party and declares that he is challenging Frankie to a game where the pair race to see who can push a peanut across the floor with their noses the fastest. Frankie had previously lost to Petey in this game when they were children, and the nearly throwaway scene features the nearly throwaway line that I think tells us more about Frankie’s true motivations than any line of the narration: “I’m giving you a second chance! Very few people get that in their life.” The line isn’t given any special importance, Petey just uses it to try to convince Frankie to play. The peanut pushing contest represents a return to childhood innocence to Frankie, a childhood that he only rarely got to truly enjoy and that turned him into an apparently heartless killer. There is plenty of evidence pointing towards this being Frankie’s true motivation—from the opening narration to his relationship with Christmas to falling in love with a girl that he knew as a child. Although Frankie wins the peanut contest, he is never able to reclaim that innocence—he never truly gets the second chance that he so desperately desired.

Dude why you gotta give away the whole plot in the first paragraph?!