In what has to sound like as complex a self-reflexive remake as imaginable, this month in the new HBO limited series Irma Vep, directed by Olivier Assayas, Alicia Vikander will play an actress joining a limited-series remake of the 1916 French classic Les vampires, itself a limited-series remake of Assayas’s own 1996 film about an actress—then played by Hong Hong star Maggie Cheung—in a film-version remake of the Les vampires.

Whew!

I’ll be covering episodes of the HBO series each week on TV Obsessive, where I’ll try to make sense, if sense need be made, of all the above. In the meantime, in this episode of Off the Shelf, our weekly feature looking at physical media, let me offer a refresher on Assayas’s intoxicating 1996 film. And while you can indeed watch that film on HBOMax, there’s no place more satisfying to turn to for a revisit of Irma Vep than to The Criterion Collection’s 2021 two-disc remastering, a set replete with special features providing insight to the film’s inspirations and interpretation.

Irma Vep: The 1996 Film

Assayas’s 1996 Irma Vep was his international breakthrough, a lively behind-the-screen drama significantly influenced by François Truffaut’s 1973 Day for Night (La Nuit américaine). On one level, like Truffaut’s film, it’s a recognizable story of an ill-fated film production: in Assayas’s case, a remake of Louis Feuillade’s classic 1916 silent crime serial Les vampires, one of the French cinema’s seminal works. Like in Truffaut and in so, so many films-about-filmmaking, what can go wrong, will. Egos abound, passions simmer, takes fail, rushes disappoint, visions conflict, and the New Wave burnout director René Vidal (a cleverly cast Jean-Pierre Léaud, who played the star to Truffaut’s director in Day for Night as well Antoine Doinel in The 400 Blows and its sequels) teeters on the precipice of sanity.

On another level, there’s that catsuit.

International Hong Kong star Maggie Cheung plays a version of herself as the lead in the Les vampires remake. And that, to role requires her to don a tight-fitting latex catsuit, inspired both by the Irma Vep character in the Feuillade original and Michelle Pfeifer’s super-slinky Catwoman in Tim Burton’s 1992 Batman Returns. Getting that catsuit just right for Cheung’s character, a Hong Kong action-movie star, is enough to drive her costumer Zoé (Nathalie Richard) and several other characters into a frenzy. Cheung plays herself with a guileless, innocent naïveté to the passions she arouses in others, even as she begins to question Vidal’s increasingly incoherent vision and take on some aspect of her character in her own actions.

For a time, it looks like Cheung, playing in Vidal’s film the updated version of the catsuited vampire-burglar known in 1916 as “Irma Vep”—an anagram for “vampire” like Theda Bara was for “Arab death”—may be played for a victim. She’s stuffed into a catsuit, lusted after, and commanded about with little regard for her own artistry or emotions. But eventually, her character makes her own decisions and commitments, pursuing what’s best for her career regardless of others’ intentions. Her arc is ultimately one of agency over her life, career, and image.

Vidal, meanwhile, was once a talented director, but in the Cinéma du look age of the 1990s, he seems to have run out of ideas, at least ones he can express coherently. No one on his set expresses any confidence in the production of the Les vampires remake. In reference to the film Vidal is making on set, but indirectly questioning Assayas’s film itself (and perhaps, who knows, his 2022 series), Zoé asks:

Why do we what’s already been done?

It’s an existential question aimed at the heart of French cinema and one which Irma Vep foregrounds: is the way forward mimicking that of the American blockbuster both profess to loathe? Trying to resuscitate the glories of the Nouvelle Vague movement (of which Léaud was once the face of its anti-establishment rebelliousness)? Adopting the sleek, stylish Cinéma du look of Besson, Beineix, and Carax? (For the record, Vidal chooses an anarchic, postmodernist bricolage more like Stan Brakhage or Guy Maddin than any of these; whether it makes any sense or will ever be seen is an open question.)

The film Vidal makes seems, ultimately, almost besides the point. He has no answers—just Maggie Cheung in a catsuit and a crew of malcontents. But Olivier Assayas in his film Irma Vep does (and he has Maggie Cheung in a catsuit too, for what that’s worth). Assayas’s is a potent, heady brew of past, present, and future, mixing silent-cinema imagery, New-wave intimacy, arthouse cool, and martial-arts action, with just a bit of du look panache. Add in the postmodern cool of a music track with contributions from Sonic Youth and Luna (themselves remaking a French hit about Americans!), and Assayas’s Irma Vep is a one-of-a-kind film in a recognizable genre of films-about-filmmaking.

Assayas’s film is both highly specific in its critique of the French film industry of the moment and applicable to a broader question raised by almost every film-about-film, from Stand-In, Sullivan’s Travels, and In a Lonely Place to The Player, Adaptation, and Somewhere: the tension between art and commerce that has always been at the center of filmmaking. As a kind of pan-art that relies heavily on existing narratives and requires funding to create, film is always subject to commercial constraints—and that fact weighs heavily on many a filmmaker.

At first a writer, like Truffaut for Cahiers du Cinéma, then a director, and later for a time married to Cheung, Assayas is an intellectual filmmaker whose pursuits are always cognizant of the industry around him, both in his native France and worldwide. Until his remake series of Irma Vep is released, it’s difficult to know his intentions for a 2022 version; his 1996 film, though not necessarily universally embraced, certainly seems a fully-formed, highly idiosyncratic, and ultimately beguiling look at an industry that was then, and is again now, in crisis.

Released in 2021, Criterion’s two-disc Blu-ray edition of the film offers a handsome 2k digital restoration of the film supervised by Assayas in its original 1.66:1 aspect ratio and with a 5.1 surround DTS-HD Master Audio soundtrack. The remaster is sharp and detailed with striking contrast between those scenes shot in the film’s present (with Cheung, Léaud, and Richard on set), the repurposed silent footage of Feuillade, and the remake arthouse film Léaud’s character is directing. With spotless clarity, Assayas’s film looks—and sounds—impeccable on this release, its first on Blu-ray. Given that Cheung’s character speaks little or no French, about half of the film (in particular, whenever Cheung is in dialogue with another character) is spoken in English; the rest of the film is in French. Some English-native speakers may find Léaud’s accent in particular thick enough to necessitate activating the SDH track: he’s especially soft-spoken and given to hesitant mumbling about his artistic inventions.

Given the excellence of Criterion’s remaster of the film, I’m very much looking forward to seeing Assayas’s remake of his own film. Like this film, it’s likely to offer a thoughtful meditation on the adaptive and consumptive elements of the creative process. Will it, too, feature the naturalistic, hand-held, intimate casualness so evident in the film’s production scenes, or will it adopt more of a mannered, glossy sheen, as the teaser trailer seems to suggest? Will Assayas again use Feuillade or show us the film made by his fictional director Vidal? While his 1996 Irma Vep is a film that largely eschews narrative convention and employs ellipsis as a means of advancing plotlines, will the eight-episode structure do more to fill in gaps, or will it take the story in new directions?

Last year, writer-director Hagai Levy adapted Ingmar Bergman’s classic television series Scenes from a Marriage, updating the setting and reversing the gender roles while hewing closely to its narrative structure, even adopting the same episode titles and, sometimes, dialogue. But he was working with a canonical director’s content. Assayas will be working with his own, and I assume he will feel as free to rethink his earlier film for a streaming era in whatever ways please him, while still using its basic plotline and alluding to its iconic imagery. We shall see!

Special Features

As is so often the case with The Criterion Collection’s disc packages, Irma Vep offers a deep dive into the production and reception of the film with a trove of special features. There is, surprisingly for the degree of filmmaker participation, no commentary track. I will confess I would have loved one, whether from Assayas himself or from a critic like, say, a Walter Metz, who has written on the film’s reflexivity in Film Comment, or Aliza Ma, whose excellent essay “Irma Vep: Film in Flux” is included in the case’s insert. (An earlier Zeitgeist Films special edition DVD had included an audio commentary from Assayas and critic Jean-Michel Frodon, but that was only a recording of a stage discussion at following a Berkeley film screening, and one not at all synchronized with the film’s content.) Criterion’s special features focus primarily on the film’s production, its star Maggie Cheung, and on its iconic source material.

Olivier Assayas

In a new 29-minute interview conducted for Criterion in 2021 (probably via Zoom, to gauge from the lackluster audio-video quality), the director discusses the origins of Irma Vep, his fascination with Maggie Cheung, and his own work more broadly, especially in terms of his prior commercial failures and experimental leanings. Assayas’s insights on the original Irma Vep, the catsuited villain-hero of Les vampires, are helpful to understanding his making of the 1996 film. Assayas is, perhaps unsurprisingly, more sanguine than many about Irma Vep‘s ending and the film his fictional director René Vidal was ultimately to make. The interview is intercut with stills and clips from Assayas’s films and others, with a significant focus on Cheung and the relationship between star and filmmaker depicted in Irma Vep. The interview is conducted in English, but without SDH subtitles.

On the Set of Irma Vep

This 30-minute featurette consists of behind-the-scenes footage shot on set of the 1996 production. While the footage has a certain mini-dv je nais sais quoi, it consists primarily of crew members standing about, shooting scenes, prepping material, rehearsing, and watching rushes, without a great deal of insight or revelation. The fly-on-the-wall perspective illustrates just what those shoots were like. In French (mostly) with English SDH subtitles.

Oliver Assayas and Charles Tesson

In this 34-minute 2003 interview, Assayas and film critic Charles Tesson discuss a trip the two made to Hong Kong in 1984 in an attempt to learn and map Asian cinema generally and Hong Kong cinema specifically. Conducted entirely in French and with English SDH subtitles, this interview lacks any visual content other than the interviewees themselves, but features a highly spirited, animated interaction between the two and their unnamed interviewer. The two also discuss, to lesser extent, Maggie Cheung’s international stardom as “the essence of cinema” and her casting in Irma Vep. This interview will appeal more to fans of Asian and world cinema than to those looking for insights specific to this specific film of Assayas’s.

Maggie Cheung and Nathalie Richard

This 2003 interview with actresses Maggie Cheung and Nathalie Richard focuses nearly exclusively on the making of Irma Vep. As appropriate to the polyglot production, Cheung (raised in Great Britain and Hong Kong) speaks in English, Richard in French, with forced subtitles appearing in the “opposite” language respectively. Dressed in contrasting white and black tank tops, the two are highly attentive and animated in their recollections of their casting and the film’s productions: for instance, for Richard, the Feuillade films were an important part of her childhood and cultural heritage, while Cheung, a novice to French film, was like her character coming to the set an outsider unfamiliar to the environment and tradition.

Musidora, the Tenth Muse

This fascinating hourlong documentary, replete with interviews with the actress and others, silent film clips, archival materials, and an incredible array of early-20th-century artwork depicting the star, examines the life and legacy of Musidora, who originated the role of Irma Vep in Les Vampires. Produced by Patrick Cazals in 2013 and recorded in French, with English subtitles, the documentary traces her stardom and art in framing the actor as far more than a figure in a catsuit but as a veritable intellectual force in French film.

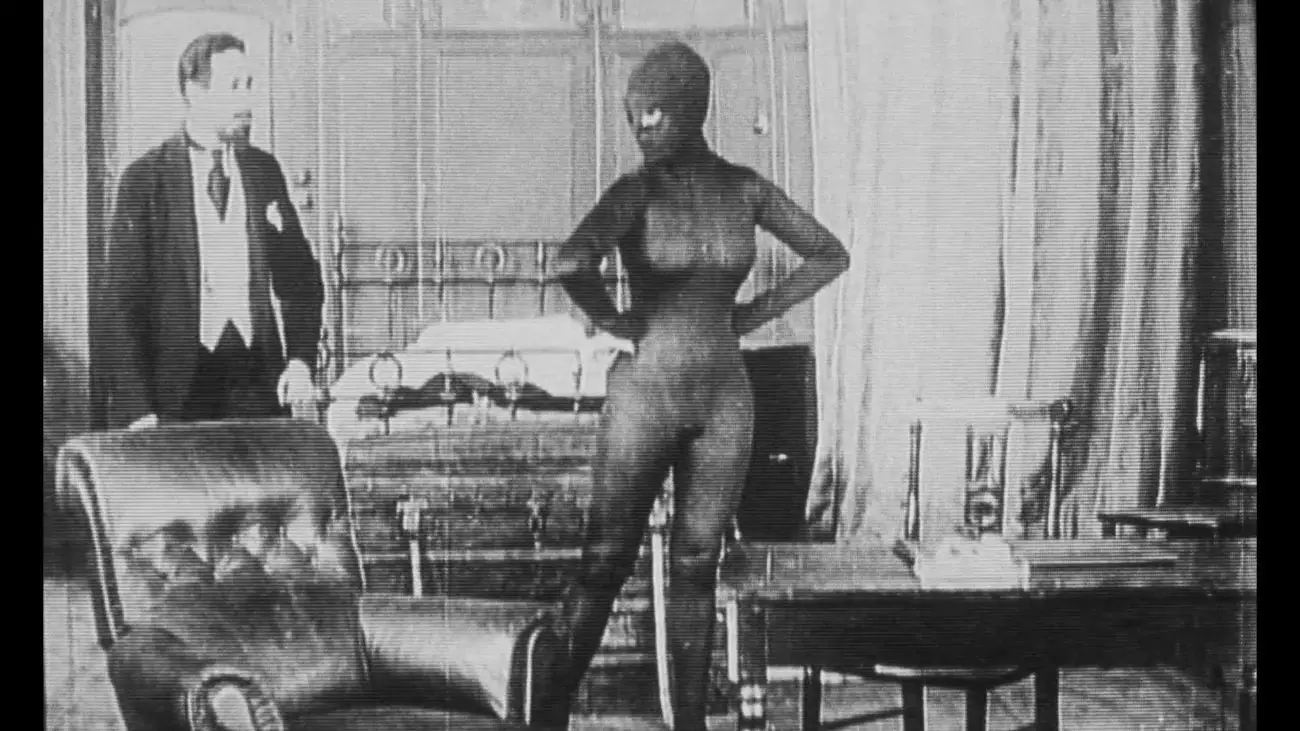

Les Vampires: Hypnotic Eyes

From 1916, the sixth of ten episodes in Louis Feuillade’s silent-film serial is a delight, presented here in excellent video quality. The episode is the one featured in Assayas’s Irma Vep, with the character Irma Vep, a member of the criminal mastermind group Les Vampires (who are not vampires in the blood-sucking undead sense), in her famous catsuit. Featuring characters in various disguises, a murder, a theft, a chase, a bullfight, hypnosis, and about a dozen other wild machinations, the dizzying plot can’t eclipse the episode’s charm, and for an early silent film the cinematic compositions and editing are first-rate.

The entirety of the serial can be found today online, where you can begin with Episode One, “The Severed Head,” to get a sense of the fuller serial, but the presentation of this specific episode is a valuable contribution to the set—and to the art of Assayas’s Irma Vep more broadly.

Cinema in the Present Tense

Having been invited by the cinema magazine Sabzian to deliver a keynote on “the current state of cinema,” Assayas’s scheduled March 2020 address was made impossible by Covid and delivered virtually instead. His wide-ranging, highly intellectual, and thought-provoking address begins: “I have some good news, for everyone: cinema is in crisis. Which is hardly news, in a way, for it has continuously been in crisis throughout its existence.” Citing his influences and contemporaries, alluding to scholars like Hockney and Deleuze, questioning the “dead ideologies” of the universities, and posing direct questions of the influence of streaming services, Assayas delivers a remarkable, if diffuse, defense of cinema as narrative art. The address consists entirely of Assayas reading the script of his talk on his computer’s webcam—though he does so with passion and verve—and no other visual content, in French, with optional English subtitles.

A translation of his address by Sis Matthé is additionally available at the Sabzian website.

Man Yuk

This short, silent (completely silent, that is, with no music at all) film made by Assayas in 1997, features a close-up portrait of Maggie Cheung, whom Assayas would marry the following year. Commissioned for the Foundation Cartier pour l’art contemporain in Paris, the film depicts a few minutes of Cheung in close-up, much of it focusing on her (apparently rigorous and highly successful) skincare regimen.

Black-and-white rushes

These four minutes of silent rushes from the shooting of Irma Vep consist entirely of footage of Cheung in her catsuit striding across Parisian rooftops in various pensive moods and athletic poses.

“Irma Vep: Film in Flux”

This excellent, wide-ranging essay by Aliza Ma focuses on Assayas’s career more broadly, looking at the mediated thematics of his films and his ability to ground abstract philosophical concerns in more specific, tangible scenarios. With special attention to the casting of Cheung and the iconicity of her catsuit costume, Ma details the film’s exploration of artistic authenticity and credibility. The essay is also available online at Criterion.com. Ma is founding head of programming at New York’s Metrograph, and her essay on the film is a must-read.

Final Thoughts

As is often the case, The Criterion Collection’s remastering and repackaging of modern classics like Irma Vep is well worth any cinephile’s while. Irma Vep is a fascinating film, at once an exploration of national cinema in a transnational era, of the challenges of the star and director (and others!) in the production phase of filmmaking, and of the tensions between art and commerce. It’s a seminal work in Assayas’s and Cheung’s careers both and an important work in postmodern world cinema.

It’s also something of an acquired taste, a film that has never been universally embraced but that seems more specific to the concerns of artists and cineastes than to the general public. But Criterion’s handsome remaster and special-features packaging paint a much fuller, multiperspectival portrait of this unusual film-about-film. Assayas and Cheung are both thoughtful, intelligent defenders of their work who exude passion and dedication.

It won’t be necessary to “deep-dive” the totality of Criterion’s two-disc bouquet of Irma Vep and its special features to prepare for HBO’s eight-episode series, but anyone interested in Assayas’s film or its making will likely find themselves deeply immersed in, and delighted by, this edition. I only hope that Assayas and series star Alicia Vikander can bring to the HBO series the same kind of passion and creativity that informed the 1996 version of Irma Vep.