Now that the art form is well over a century old, remakes of older films in recent years have become more prevalent. The film industry wants to minimize the risk of audience disinterest towards a unique premise that isn’t guaranteed financial success in the world of marketing and box office numbers. However, directors would like to create a well-crafted product when working on a remake, even though the inherently unexciting nature of filming a remake adds to the typical problems that can occur during a film. In Olivier Assayas’s breakthrough film Irma Vep (1996), Assayas analyzes the contemporary film industry by questioning the purpose of a remake, showing the chaotic nature of troubled film productions and the transformative aspect of film acting. Just as Olivier Assayas was able to create an interesting discourse on the nature of filming 25 years ago, Irma Vep (1996) has become more prescient in its portrayal of the film industry to this very day.

One of the major characteristics that make the film relevant today is that it questions the validity and purpose of a remake. From the very beginning, all the various crew members of the film, including director René Vidal (Jean-Pierre Léaud), fail to try to explain the decision to remake the French crime serial Les Vampires (1915-16) to various outside members, including the main star Maggie Cheung (playing herself within the film), who’s hired to play the character of Irma Vep in the remake. Remakes, on a fundamental level, are difficult to justify artistically. An original film like Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956) had to exist for the various remakes, such as Philip Kaufman’s 1978 version, or Abel Ferrara’s 1993 version, to subsequently exist, even if they take some creative liberties such as different characters or settings. Furthermore, the existence of shot-for-shot remakes like Gus Van Sant’s 1998 remake of Psycho (1960), or Micheal Haneke creating a 2007 English-language copy of his Austrian film Funny Games (1997) becomes more confounding since they lack any sort of intrigue or suspense that original art can have. The original is a blank-slate experience instead of a retread.

Another way that Assayas questions the purpose of a remake is by having the various crew members struggle to explain the choice to remake a silent crime serial that has a runtime exceeding 7 hours when remaking a 90 to 120-minute film would make more sense from a marketing and financial perspective. When remaking a film, the more acclaimed the original, the wider the audience appeal is. For example, there’s a built-in legacy in remaking a classic like Halloween (1978) for the 21st century due to decades of built-upon legacy, resulting in renewed interest due to its revived presence in theaters. Furthermore, the more contemporary a classic is, the easier it is to remake it, as the original would have easily replicable filming techniques and plot structure since it would be fresher than a multi-decades-old silent film where various techniques—such as intertitles and frame rates below the industry standard 24 frames per second—have been abandoned due to their dated nature.

Irma Vep continues to be relevant today through its portrayal of a chaotic filming environment of a troubled production. Even before Maggie Cheung arrives on set 3 days late, the production is shown rushing as the film company loses money on the extended filming schedule and the film crew becomes stressed in trying to speed along the production. In recent years, a rushed production resulted in disastrous financial and critical flops such as The Snowman (2017), where director Tomas Alfredson was not allowed to film 10 to 15 percent of the screenplay, resulting in a jumbled and confusing mess. The detective story had missing sequences that wouldn’t allow the mystery to wrap up within the film. Furthermore, Tom Hooper’s Cats (2019) had visuals being worked on until the release day, and then the film was re-released with changed visuals nearly a week after it had already been put in theaters. The film’s tight schedule caused the film to suffer because meant the film’s digital visuals didn’t have time to naturally improve due to being forced on a rigid release time window, making the visuals come out unappealing and uncanny.

Furthermore, the production is depicted as negatively impacting the film is René being pulled from the film after suffering mentally from the stress of the film set. This showcase of stress negatively impacting the work of a director can be seen in Terry Gilliam’s long-time troubled production of The Man Who Killed Don Quixote (2018), as various weather interruptions and actor injuries forced Gilliam to place the project on hiatus, which can be seen in the behind-the-scenes filming documentary of Lost In La Mancha (2002), which revolved in one of the failed filming attempts. Even when a film is complete, the director of a film can still be negatively impacted by stress, like when Richard Kelly removing 20 minutes from his cut of Southland Tales (2006) after a disastrous critical viewing in the Cannes Film Festival, where the director had been eager to follow-up his debut with a well-regarded sophomore effort. As a result of the initially hostile first impressions, the film was never able to receive proper unobstructed viewing due to cut scenes being a result of pressure for a rising director.

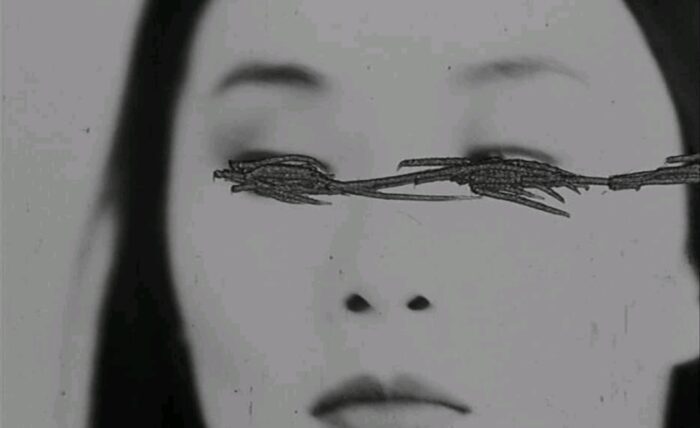

A final characteristic of the film that makes it relevant today is the highlighted connection between film role and identity for an actor/actress. As Maggie Cheung spends more time participating in the various scenes of the remake, she suddenly starts to become sleepy as she takes the sly mannerisms of her Irma Vep character. She also starts to sneak around at night for no discernible reason. These scenes of Maggie Cheung acting like her character off of the set brings an almost method-like quality to her character, relating her to a method actor like Christian Bale, who will lose weight to properly portray a person with a drug addiction in The Fighter (2010), or gain weight to accurately represent the real-life figure of Dick Cheney in Vice (2018). Even in Olivier Assayas’s later filmography, actor Édgar Ramírez changed haircuts, styles, and body weights to portray the titular role in Carlos (2010) by showing the ever-changing appearance of a man in a world that evolves throughout the decades with him, making the role vibrant as the actor is willing to sacrifice time and their health to become immersed in their character, and as a result, make their portrayal seem more authentic towards a viewing audience.

With its questions about the purpose of film remakes, the consequences of a troubled production on a film, and by highlighting the transformation an actor/actress can go through when playing a role, Irma Vep (1996) is as relevant in its portrayal of the modern film industry as it was 25 years ago. Even though Olivier Assayas does not hold back in showing the shortcomings of the film industry, the film ends on an optimistic note that the art form is still an enjoyable experience for individuals willing to express and challenge themselves. Just as Maggie Cheung and all the other characters assemble to watch the scrambled, scratched, and rapid film footage of the remake scenes, the love for cinema is apparent even in the harshest of images that are projected through.