The Criterion Collection started in 1984 with the mission of “publishing important classic and contemporary films from around the world in editions that offer the highest technical quality and award-winning, original supplements”. With minimalist artwork and an ever-increasing, always eclectic library that has expanded to 966 titles to date (with twenty more pending) indicated by their collector-enticing spine number, Criterion set itself apart as “important” cinema without seeming obnoxious about it. Criterion was cool because it was curated by genuine movie lovers who dipped into multiple genres, countries, and decades.

When I was in my late teens, just after the turn of the century, Criterion discs were the expensive and exotic items you found in specialized DVD shops. It wasn’t easy to find a Criterion film at the local Blockbuster for rent or at Best Buy to purchase unless it was one of the rare “popular” titles the Collection released (such as Michael Bay’s The Rock or Kevin Smith’s Chasing Amy). I was usually priced-out of Criterion purchases myself but was always wondering what exotic magic lay within the case of those DVDs.

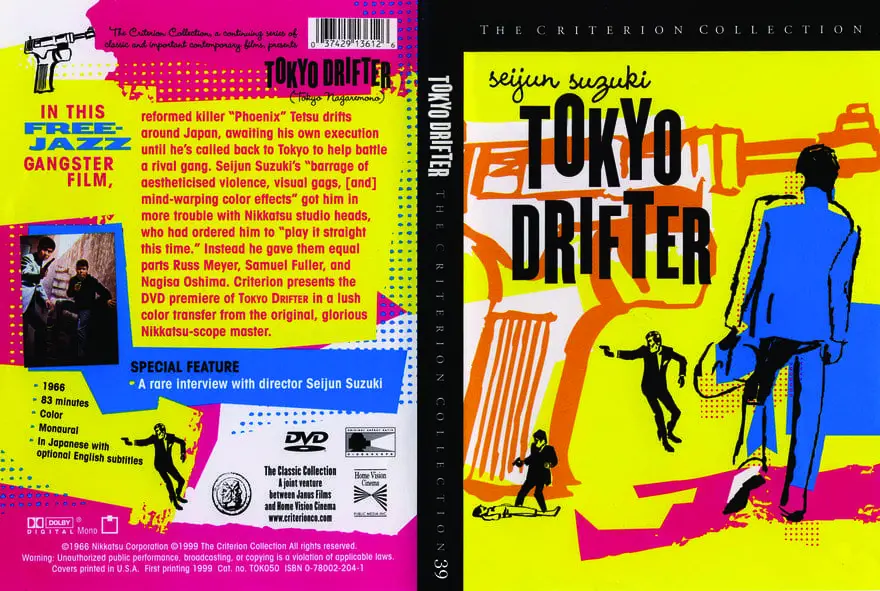

By chance, I visited the Virgin Megastore in Times Square on a school trip to New York City sometime in 2000. I decided to splurge on what was the irresistible (and expensive) Criterion Collection DVD of Tokyo Drifter (directed by Seijun Suzuki and released in 1966; spine #39). I hadn’t seen the film at all. I judged the book (er, film) by its cover and bought it. I was both an amateur Japanese historian and a James Bond fanatic then and the bright colors, retro-Bond look, and Japanese director’s name all said: “buy me”, sight unseen.

And what could have been a costly failed experiment ended up literally changing my life. I will admit—as a lot of green film nerds are in their youth—that I was a big studio kind of guy. I liked the indie craze of the ’90s, but I didn’t go too deep into that culture outside of the heavyweights, like Smith, Tarantino, Ed Burns. I was an avid film viewer but not an experimenter. Tokyo Drifter not only opened my eyes to world cinema but it also increased my desire to discover Japanese culture, seek out older films, and take more risks at the cinema itself: finding art houses and big screen re-releases of classics.

While I never really bought too many Criterion discs themselves from that great moment in 2000 to even just a few years ago—due to price and availability—my mind was fully expanded and I never approached cinema the same. Some of you that know me and my intense Marvel fandom might question how I could be into independent/world cinema when I worship the most successful, commercial film franchise in history in the MCU. My answer: film isn’t objective and it certainly isn’t a contest.

Criterion never dictated what you had to like and it never told you what is “fake”, what is “pretentious”, or what is not to be consumed and I’ve taken that to heart, be it binging art house films made for $16 or the multiplex blockbuster grossing $2 billion. Movies are all about experience and sometimes a film hated by 99 people is loved by one. Criterion fosters that love and, most importantly, educates you.

So, as time passed, I became particularly invested in Japanese cinema and their diverse group of directors. And now that the Criterion Channel is available at a ridiculously low price, I figured I’d share with you some of my experiences with notable Japanese filmmakers and their unique movies that are available on this new streaming service.

Much like Criterion itself, I wanted to curate this experience so that if you are interested in getting into Japanese cinema, this list of both popular titles and deeper cuts would be a good start. My choices are wide-ranging and eclectic, and there are even some I didn’t particularly like but find redeeming or at least worth a viewing. In the end, these films are yours to discover and examine, without judgment (though, naturally, I will be giving you my opinion).

Rashomon (1950)

Director: Akira Kurosawa

Story: A near-crazed vagabond is on trial for the rape of a young woman and the death of her samurai husband. While the vagabond Tajomaru, a known criminal, has his own story to tell, so does the rape victim (The Wife), the dead Samurai (through magic), and a key but silent witness. A tale of individual interpretation and personal motivation, the truth remains in the eye of the beholder.

Thoughts and Analysis: Besides giving birth to a new narrative structure dubbed “The Rashomon Effect” (one of which takes the unreliable narrator concept to the extreme), Kurosawa’s blend of sensitive and/or complex subjects such as rape, honor, and thievery was bold for a country still under American occupation at the time of the film’s production and struggling with not only its identity but of rebuilding from the ground up, quite literally.

Only five years removed from the atomic bombs being dropped and the complete upheaval of political and social structures, Japan likely had differing views of certain events. Though the country, on the whole, had turned to pacifism and assimilated to a lot of American culture as it settled alongside them, many families lost sons in the war, had old political ties, and beliefs in the Emperor as a God. It is hard to switch those beliefs off right away, and certain generations would hold ideals and concepts differently than those born or coming of age in a post-Imperial Japan.

Thus, Rashomon functions as a fantastic metaphor for Japan’s then-current state: one in which many witnessed the same events but came out with different ideas of what happened. Buoyed by the infectious kineticism of Toshiro Mifune (as Tajomaru) and the breathtaking black and white cinematography of Kazuo Miyagawa, Rashomon also functions as just pure entertainment without any historical baggage. It is a true classic, currently rated #115 on the greatest films of all-time by users of IMDB.

If You Want More Kurosawa: Kurosawa is one of the legends of cinema, in Japan and the rest of the world. Popular Titles include Seven Samurai (1954), Throne of Blood (1957), The Hidden Fortress (1958), and Yojimbo (1961). Deeper Cuts: Ikiru (1952), The Lower Depths (1957), and The Bad Sleep Well (1960). All are available on the Criterion Channel.

In The Realm of the Senses (1976)

Director: Nagisa Oshima

Story: Set in pre-war 1930s Japan, Maid-turned-wife Sada Abe engages in increasingly more daring sexual activity with her former boss-now-husband Kichizo Ishida. As her obsessions ramp up, so does her proclivity for danger and violence. In the end, sex and death may be one and the same.

Thoughts and Analysis: The “I Know It When I See It” statement has long been applied to rebellious and controversial art. In the case of In The Realm Of the Senses, in which a tale of obsessive sexual desire is shown as graphically real, including shots of unsimulated sex and actual masturbation, one has to determine if, due to high production values and artistic pursuit of realism, one can call the film pornographic.

Oshima’s visceral filmmaking is certainly revolutionary. It is not often you see such raw sexuality up close in such pristine surroundings and with such grand cinematography. There is something almost documentary-like to seeing “normal” looking human beings engage in an activity that can sometimes be messy and awkward. However, whether it is an artistic excuse to be titillating or a pornographic way to be arty is up to the eye of the beholder.

Set in pre-war Imperial Japan in the 1930s, it certainly helps if you know where Japan was at that time to understand the upheaval surrounding the country. You had the mixture of traditional Japanese architecture and societal norms up against a technical revolution. And Oshima does show the obliviousness of the main characters to the rapid change around them.

However, for me, I felt like there was too much sex and not enough story (or at least not a strong enough narrative throughline) to justify its existence. Though I can’t claim it is gratuitous, exactly, the story gets bogged down by a lot of repetition that involves sex. I feel like Sada Abe’s obsessions could be more subtly deployed but I’m also not a legendary filmmaker, so what do I know?

This Japanese film is still required viewing as it can’t even be shown in Japan today due to the restrictions on the depiction of sex. And, if anything, it is an aesthetic marvel, perfectly capturing the 1930s and Japan’s exotic and unique architecture and fashion.

If You Want More Oshima: A rebel of cinema, at home and abroad, Oshima’s other films might not be as sexually explicit as In the Realm of the Senses, but almost as controversial. Arguably, his most well-known film is Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence (1983) starring David Bowie and future Japanese directing icon “Beat” Takeshi Kitano about Allied POWs in a Japanese internment camp. Other Criterion available Oshima titles include the political Night and Fog in Japan (1960) and the sexually dense films Empire of Passion (1970) and Diary of a Shinjuku Thief (1969).

Tokyo Drifter (1966)

Director: Seijun Suzuki

Story: Legendary yakuza enforcer “Phoenix Tetsu” is on the straight and narrow, looking to move beyond the criminal lifestyle. However, sinister yakuza groups seek to exploit Tetsu’s former boss (also going legitimate) and want Tetsu either with them or out of the picture. Forced to roam Japan as a vagabond, and avoid countless attempts on his life, the “Drifter” plans his return to Tokyo to avenge those who’ve wronged him.

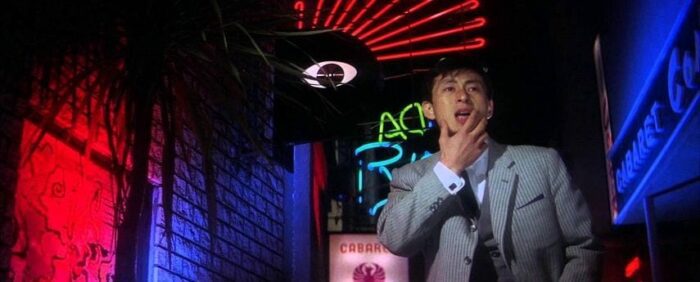

Thoughts and Analysis: A lot of my thoughts on Tokyo Drifter were in the introduction but I can’t emphasize this enough: this movie is cool, cool, cool! Unlike most of the other films on the list, Tokyo Drifter has no approach to realism, instead going for a mix of art-deco fantasy and pop-art insanity.

At the time of Tokyo Drifter, Sean Connery had portrayed James Bond four times (and was about to make a fifth appearance, set in Japan itself, in 1967). Known for their highly colorful palette and stylish approach to espionage, the Bond films inspired lots of imitators. Most just copied what Bond did to lesser effect but unique approaches by the Italians (1968’s Danger: Diabolik) and Japanese (mostly through Suzuki with Tokyo Drifter and Branded to Kill) set itself apart by paying homage to Bond but staying unique to that country’s character.

Post-Olympics Japan was very modern and full of complex societal trends, mixing the unique look of its past with the modernization and reconstruction post-War leading to a sometimes overwhelming cacophony of images and sounds. Tokyo Drifter’s set design evokes a European feel, and the dance sequences and musical queues feel like swingin’ London baby.

The plot is ridiculously complex and the most interesting character trait of our heroes and villains is their choice of clothing, but this is a deliberate, artistic choice. This is an animated film made flesh meant to evoke “oohs” and “ahhs” from its audience, not reinvent the wheel.

If You Want More Suzuki: Criterion has it’s own dedicated feature to Suzuki called “The Chaos of Cool”, a collection of seven films showing Suzuki’s art-deco brand of highly stylized yakuza/crime films. Titles include: Branded to Kill (1967), Youth of the Beast (1963), Gate of Flesh (1964), and Take Aim At the Police Van (1960).

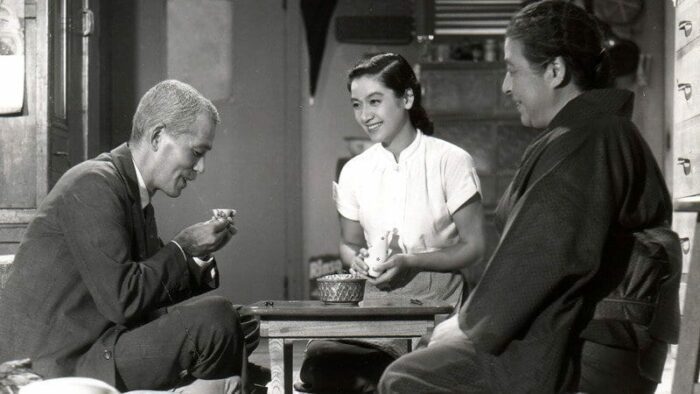

Tokyo Story (1953)

Director: Yasujiro Ozu

Story: Two elderly parents from far outside the city (Shukichi and Tomi) visit their surviving children in Tokyo for the first time, anxious to see more of their home country and their grown family. However, they are met with indifference by their kids, who are distracted by their own concerns. Either left to explore on their own or pushed to exotic locales that don’t suit them by the children who have no idea what to do with them, the parents reach the winter of their lives surrounded yet alone.

Thoughts and Analysis: Of all the films featured in this article, Tokyo Story may be the most emotionally devastating. And that is an impressive achievement because the film looks at the subtleties of life at a languid pace, overseeing the commonly unobserved moments of living with characters who spend more time reflecting than actually conversing.

In a truly timeless tale that could take place anywhere, not specifically the Japan of the ’50s, Tokyo Story looks at the inevitability of death, how families grow apart in an increasingly more modern world, and how generations change their outlooks on family life as they also begin to multiply and literally expand into more territories previously unopened.

And to the contrary of the plot described, the film is neither maudlin or wholesome. Even the children of our protagonist parents, who come across sometimes as cold and/or too busy for their elders, have complicated work and social lives that can excuse away their actions or, at least, soften our distaste for them. But the elder parents are also given subtle shades of grey. The father, Shukichi, may have had a serious drinking problem that lays heavy over the children and his wife Tomi, for example. In essence, Ozu taps into real human relationships: not everything is roses but neither is it storm clouds and rough seas.

The true find of this film is actress Setsuko Hara as Noriko, daughter-in-law to Shukichi and Tomu. Noriko was married to Shukichi and Tomi’s son, who died during World War II. Respectful of her marriage, even eight years later, and entirely devoted to Shukichi and Tomi, Hara is tear-jerkingly loyal and shows that you don’t even have to be a blood relative to truly be family. Hara is such a beautiful actress and her tender nature shoots through the screen and into your heart.

If You Want More Ozu: Ozu is a Japanese filmmaking legend on par with (though not as popular as) Akira Kurosawa. His films are inspirations to many. Randomly, I tweeted the other day that both Tokyo Story and the film Logan, with Hugh Jackman, are surprisingly similar in theme and scope. Logan’s director, James Mangold, replied to me and said that both Ozu and Tokyo Story itself was his prime artistic inspiration.

If you want to dig deeper, Criterion has 33 total Ozu films available to stream. Some of his other most popular titles include Floating Weeds (1959), A Hen in the Wind (1948) and Late Spring (1949).

Black Sun (1964)

Director: Koreyoshi Kurahara

Story: A jazz-crazed Japanese vagabond named Mei roams through Tokyo, looking to beg, borrow, and steal his way for every meal and, more importantly, every jazz record. At the abandoned church where he squats, Mei stumbles onto a black, wounded GI named Gill, wanted for murder. With no means of communication and massively incorrect stereotypical assumptions about each other, the two trade off taking each other hostage before they must unite to escape the police.

Thoughts and Analysis: “Bonkers” is perhaps the key word when describing Black Sun. As if trapped in an LSD nightmare from an insane jazz drummer, Black Sun moves at such a quick, frantic pace that you can’t help but shake your head when the whole thing is over. It is easy to think “this movie is just cooooool baby” when watching it, but Kurahara’s world is full of single-minded grifters and racially insensitive whackos living the most selfish of lifestyles.

Mei, in particular, is a bizarre creature: obsessed with jazz legends, so much so that pictures of them adorn the walls of his “room” in the abandoned church he lives in, Mei assumes all black people are jazz musicians and must be super-human. Thus when Gill comes into his life, fading towards death from a continually untreated gunshot wound, pointing a gun and demanding to be taken to the sea to return to his mother and unable to play the trumpet, Mei presumes he is a race traitor and then, horribly, assumes all black people are like him and swears off jazz forever.

As most films of this nature do, the two do become friends by the end but insane sequences of Mei donning blackface, Gill adorning kabuki makeup, and the two yelling racial epithets at each other can be pretty harrowing and shocking. Throw in a surprising amount of sexuality for the ’60s and a troop of unlikable characters (such as Mei’s jazz buddies who expect the “darky” to dance), and Black Sun might be mistaken for bad taste.

Yet, it is so deliciously insane and specifically stylized that you can’t help but be enthralled by it. Add in the aforementioned frenetic pace that allows for no reflection and you come to realize that Black Sun provides a devastating social commentary on race relations, especially in a country dealing with the fall-out of World War II and its own history of race-related brutality. The fact that a Japanese director provides such a scathing send-up of race relations in his own country makes it all the more powerful. Sometimes feeling uncomfortable is the sign of real art.

If You Want More Kurahara: Six films of Kurahara’s exist on the Criterion Channel, including the film noirs Intimidation (1960), and I Am Waiting (1957), the Black Sun weirdo antecedent The Warped Ones (1960), and the drama Thirst For Love (1967).

Tokyo Olympiad (1965)

Director: Kon Ichikawa

Story: The “official” film from the government of Japan, documenting the historic 18th Olympic Games, held in Tokyo. Initially considered a promotional project, Director Ichikawa verged from the producers intended purpose, detailing the intimate moments with athletes and the minutiae of specific events. Alternate cuts exist, as forced by the government, but this Criterion version is Ichikawa’s specific vision of triumph, failure, isolation, and focus without revision.

Thoughts and Analysis: An entire article could be dedicated to this film alone as what is an essentially narrative-less story can explain so much about Japan and the world itself in such an effective way. In fact, Tokyo Olympiad isn’t so much about other countries as it is humanity itself through the guise of competition and personal achievement.

The film itself sometimes provides contradictions instead of affirmations of competitive culture. For instance, after a gripping back-and-forth battle with the USSR to earn the gold medal in volleyball, Japan’s head volleyball coach appears overwhelmed and dejected. If you took a screenshot of him and were asked to explain his emotions, it would be easy to say “disappointed”. However, that is the enigma of sports: sometimes the pursuit of perfection can take a lot out of you.

Other sequences like this include the Ethiopian runner Abebe Bikila winning the gold for the Men’s Marathon, a 40 km race that the entire field couldn’t finish. As bodies literally hit the ground and are taken away in “relief buses”, Abebe’s face is shown in close-up, emotionless and determined. As he finishes first, the silver and bronze medalists come through, grabbing their sides and wincing in agony.

Other ironic moments exist, like when the loser of a wrestling match, smiling ear to ear, hugs his opponent, while the winner remains still, almost emotionless. This is all intercut with the pageantry of the Opening Ceremonies and the slow-motion grimaces and tweaked muscles of hurdle runners as they push and push to the Gold.

Without Ichikawa’s direction and Kazuo Miyagawa’s breathtaking color cinematography (he also was the director of photography on Rashomon), this unique, annual experience of human achievement might have been lost save for pure statistics and results in the sports history books.

If You Want More Ichikawa: Ichikawa’s non-documentary work available on the Criterion Channel includes bleak, and likely still fresh, looks at the losing efforts in World War II, including Fires on The Plain (1959) and The Burmese Harp (1956). Other intriguing titles available vary by genre and subjects, including the revenge film aptly titled An Actor’s Revenge (1963), the fantasy yarn Princess From the Moon (1987), and family dramas such as Her Brother (1960) and Being Two Isn’t Easy (1962).

Godzilla (1954)

Director: Ishiro Honda

Story: “Baptized by the fires of the H-Bomb”, a long-extinct dinosaur of the Jurassic period, dubbed Godzilla by the more traditional folks in Japan, rises from the ocean to lay waste to modern man. Only a war-hardened scientist has the weapon to defeat him, but ethically he can’t find himself using it due to its destructive potential.

Thoughts and Analysis: There might not be a more direct allegory for the trauma of the atomic bombs used on Japan than the creation of Godzilla, a massive undersea creature resurrected thanks to underwater nuclear tests and given strength by radiation. Every step he takes, as he lays waste to entire cities, is loaded with radiation and destruction. To survivors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the concept of an entire city in flames, pulverized to the ground, is an all too real one.

Godzilla was released before the 10th anniversary of the bombs dropping and the nation was still in recovery, both physically and mentally. Godzilla allowed the people to have some sort of release, both by having the Japanese themselves (no American intervention) destroy the Godzilla threat and for a Japanese scientist to develop a weapon of mass destruction and struggle with the capabilities of its use.

Though the film is apparently made on the cheap in terms of cinematography, acting, and editing, the film still stands triumphant as a historical document and a time capsule of the Japanese experience as the country went from defeated imperials to modern pacifists.

On a visceral level, the film’s budget clearly went to its production design and visual effects. While a lot of the standard visuals suffer from age and poor quality, the scale models, true masterworks of miniature art in themselves, and the explosive action choreography, not to mention the iconic Godzilla design itself, still invites “woahs” from me, despite its age.

Sure, Godzilla eventually became a little kitsch, with boring exposition scenes leading to the bread and butter of the franchise, that of giant monsters fighting each other, but nothing can touch the original in terms of historical potency and heartfelt craftsmanship.

If You Want More Honda: The Criterion Channel carries nine other Ishiro Honda films, all but one set in the Godzilla universe. Highlights include Godzilla, King of the Monsters (1956, co-directed by Terry O. Morse), Rodan (1956), Ghidorah, The Three-Headed Monster (1964), and the non-Godzilla kaiju film The War of the Gargantuas (1966).

Pigs and Battleships (1961)

Director: Shohei Imamura

Story: Set in the bustling port city of Yokosuka, home to an American military base, young Kinta tries his best to become a key figure in his local yakuza gang, doing odd jobs and assisting with collection schemes, despite pleas to quit from his struggling girlfriend Haruko, his drunk war-vet father, and his boss’s brother. Wallowing in poverty and a need to fit in, Kinta finds himself getting deeper and deeper into criminal activities. Meanwhile, Haruko feels the lure of economic relief in the form of becoming a mistress to an American.

Thoughts and Analysis: If Tokyo Drifter is the epitome of “cool” Japan, then Pigs and Battleships is the antithesis of it, showing an economically depressed town struggling with gang violence, limited job opportunities (of the legit kind), and the continual influx of American sailors. Unlike the more modern Tokyo of the ’60s, Yokosuka is a poor port town, presented in the movie as a sprawling red light district, with whorehouses, gambling establishments, and dance halls surrounded by crumbling ghettos and shops struggling for survival.

Pigs and Battleships is nihilism made flesh, not particularly criticizing Japanese gangs and American military specifically, but humanity in general. Tinka is the classic tragic hero of the story: a good heart wrapped up with the wrong people. We see Tinka at the beginning of his crossroads between goofy, second-rate delivery boy to a component of more complex crimes. Alternatively, we see Haruko, still holding on to her virtue, as getting deeper and deeper into the prostitution game. First, it’s dating for money but then the offers for one-night adventures and permanent positions as a mistress to lonely soldiers pile up, offering freedom from the ghetto.

Both Tinka and Haruko suffer hardships for their decisions, ranging from family ostracization to physical harm. And as a new battleship enters the port at the end of the film, sending in new sailors to the freshly made up girls flocking towards them, it shows that what happens to Tinka and Haruko is universal in Yokosuka and neverending.

If You Want More Imamura: Imamura won two Palme d’Or at Cannes during his later career but most of his back catalog on the Criterion Channel comes before those high profile successes. Notable films of Imamura include Vengeance is Mine (1979), The Insect Woman (1963), and his directorial debut Stolen Desire (1958).

I’ll be returning in July with a second helping of Japanese cinema available on the Criterion Channel. But keep your eyes open for my Criterion Channel guide to selections from their noir film catalog, coming in June.

What a good article! Totally agree with your introductory remarks on the Criterion Collection. It’s serving an important purpose these days by being the gateway to world cinema. Like you described, the process of discovering CC almost unimaginably broadens our understanding of the world. For me, the Powell and Pressburger films, La Dolce Vita and Seven Samurai were the ones that got me hooked on watching foreign films.

Tokyo Drifter is on my watchlist – definitely looking forward to that one now! I like your deep cuts too.

What a good article! Totally agree with your introductory remarks on the Criterion Collection. It’s serving an important purpose these days by being the gateway to world cinema. Like you described, the process of discovering CC almost unimaginably broadens our understanding of the world. For me, the Powell and Pressburger films, La Dolce Vita and Seven Samurai were the ones that got me hooked on watching foreign films.

Tokyo Drifter is on my watchlist – definitely looking forward to that one now! I like your deep cuts too.